Old houses have a certain fascination about them. Even the most modestly constructed home can tell the history of a place and its people without saying a word.

The Halifax Regional Municipality has a wealth of homes in different architectural styles that each tell their own tale. Follow this very VERY amateur architecture enthusiast as we seek out the styles and the stories of a few historic homes in HRM.

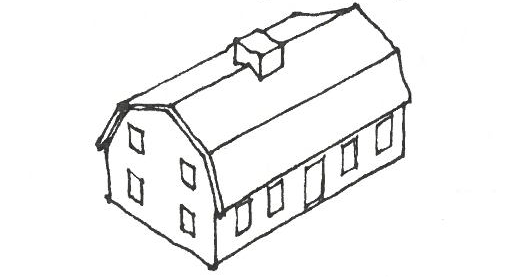

Dutch Colonial (1700-1800)

Dutch Colonial architecture is said to have originated in northern New England. Immigrants from the Netherlands resettled in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania and built their houses with a unique style. The Dutch Colonial style became very popular in the northern United States in the 1600s, and eventually, this design spread up the coast to Nova Scotia.

How do you spot a Dutch Colonial house?

Well, the first place you want to look is up. On the top of the house, you'll see a gambrel roof which has two slopes in the pitch of the roof. The result is that the outside of the home looks a lot like a barn. This double-slope design allows for more living space in the upper level of the house. Poking out of the roof, you should see either a large central chimney or two chimneys on opposite sides of the structure.

Although early New England examples of this style were constructed of brick or stone, Nova Scotia Dutch Colonial houses are usually made of wood. They stand 1 1/2 stories tall and feature a five-bay façade that typically includes a centralized doorway with windows on either side. They don't usually have dormers, but they may include small ones.

Where can I find one?

Dutch Colonial-style houses were popular in Nova Scotia throughout the 1700s, but not many are still standing in HRM.

The Scott Manor House Museum is one of the few remaining examples of this architectural style. It was built around 1770 by Irish merchant Joseph Scott. Scott came to Halifax aboard the ship London in 1749 with a group of British settlers brought to colonize Halifax. Within a short period of time, Scott set up a store on the Halifax waterfront, and later he would construct a lumber mill. He also had a bit of a political career and was appointed a justice of the peace and a judge for the Inferior Court of Common Pleas in 1752. Scott was elected to the House of Assembly.

This particular version of a Dutch Colonial home comes with a special twist! It breaks the traditional mould by standing 2 1/2 stories tall.

At the turn of the 20th century, there was a Dutch Colonial Revival and the design once again came into favour. Dutch Colonial Revival homes are easier to find in HRM because one of the plans used to help rebuild the North End after the Halifax explosion was influenced by this design. The home of Thaddeus and Mary McTiernan at the corner of Robie and Young Street is a great example of Dutch Colonial Revival. Prior to the Halifax Explosion, the McTiernans lived on Russell Street, an area in the North End that was completely devastated after the explosion. Thaddeus McTiernan was a yardmaster at the Canadian National Railway.

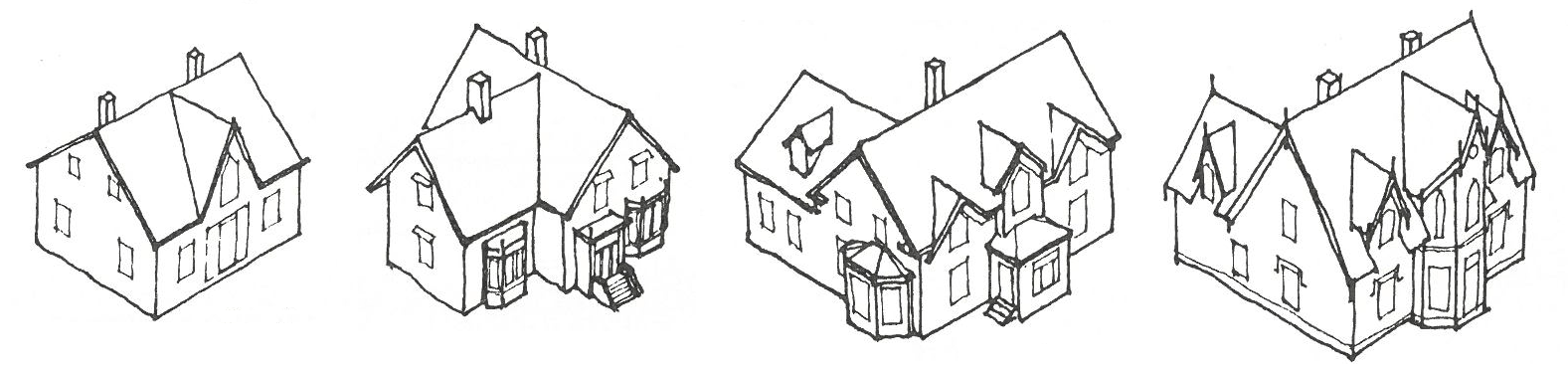

Gothic Revival (1800-1890)

Most early stone buildings were very simple structures due to the limited architectural knowledge and experience of the time. This resulted in structures that were not only plain but also cold and dark. By the mid-12th century, advancements in human skill and technology led to new designs, which helped to alleviate some of these issues. Stone buildings with vaulted ceilings, pointed arches, and pointed windows let in more light and provided better air circulation. Intricate flying buttresses better supported external walls and also acted as elaborate decoration. In a word, Gothic buildings were grand. However, they were very expensive to construct. Consequently, this style of architecture was most often seen in either castles owned by the very wealthy or in churches and cathedrals. It was very popular through to the 16th Century.

In the 1800s, a revival of Gothic architecture spread through Europe and North America; this time, it wasn't limited to religious buildings or the very wealthy. People of all economic backgrounds attempted to translate some of the grandeur and sophistication of the Gothic style into their own homes.

How do you spot a Gothic Revival house?

To spot a Gothic house in HRM, you're going to want to get straight to the point. Like their predecessors, Gothic Revival homes have lots of sharp peaks. They feature a steep-pitched gable and a precise, straight roof line. There are often dormers that echo the steep pitch of the roof itself. Windows in these homes also tend to have a point at the top to mimic the roof. The designs are usually symmetrical: a central front doorway with windows on either side that creates a mirror image three-bay façade. In Nova Scotia, these homes are most often 1 1/2 stories tall and made of wood, but more elaborate examples using different construction can also be found.

Where can I find one?

Gothic Revival architecture can be found all over the province, and HRM has some beauties.

2534 Oxford Street is an excellent example of a simplistic Gothic Revival home. Built in the late 1800s, the house features a steep-pitched gable roof with a central dormer, a centralized doorway, and a three-bay façade. City directories indicate that John Conrad (Conrod), a local tinsmith, lived in this home starting in the early 1880s. Conrad worked for both MacDonald & Co and Longard Bros. over the course of his career. MacDonald & Co was located on Barrington Street and advertised itself as "brass founders, machinists, plumbers and roofers" (1900 City Directory, pg. 344). Longard Bros promotes that they are "heating engineers and machinists... large heating and ventilating installations a specialty" (1915 City Directory, pg. 11). Conrad lived in the house with his wife until he died in 1928.

A more elaborate version of a Gothic Revival home can be found at the corner of Victoria Road and Bland Street. This home is made of brick and features a number of steeply pitched dormers on the front façade. The upper windows are Gothic in nature, with a slight point at the top of the arch, and although the front of the house has an additional ell element, it continues to maintain the traditional three-bay façade. This house is known as Grigor House because it was evidently built by one of the sons of Dr. William Grigor, a Scottish physician who immigrated to Nova Scotia in 1819 and settled in Halifax around 1824.

One of the biggest benefits of this style of house — whether simple or complex — was the steepness of the roof. The sharp slopes proved to be the perfect construction for counteracting the effects that harsh rain and heavy snow could have on a home.

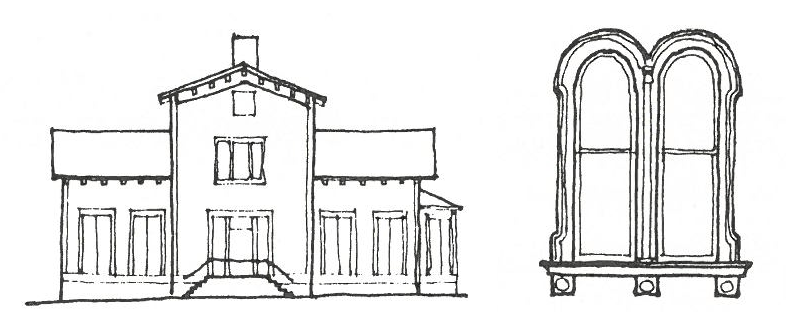

Italianate (1850 - 1870)

Picture it: Italy. The Renaissance. The delicate sweeping countryside; the warm, aromatic air; the elegant, romantic villas. It's a vision of loveliness. After settling down in rocky, rugged Nova Scotia, a person might give anything to live in a charming Italian home. So why not do it?

By the mid-1800s, English architects were introducing Mediterranean elements into their designs and the Italianate style was born. Sure, the climate in Halifax could be harsh, the countrysides weren't always pastoral, and Italy was almost 6000kms away, but that didn't stop them from living their dreams!

How do you spot an Italianate home?

One of the key features of an Italianate home is the windows. More often than not, these houses have arched windows and mouldings that make it look as if the building is surprised to see you! Another key element is a square tower, which can vary in height. It is very common for the square tower to be predominately displayed as a part of the front door, but it can be located elsewhere on the building as well. Italianate homes also tend to have decorative elements added to the trim and frieze board of the house. These homes often have a three-bay façade, and in Nova Scotia, they are typically of wood construction.

Where can I find one?

You don't need to travel far to find one of these gorgeous homes.

2500 Robie Street is an example of a home with simple Italianate features. The quintessential square tower highlights the central front door, which is lightly decorated with carved trim. These windows might not be surprised to see you, but they are at least a little curious! The first-floor windows on the façade feature just a hint of the classic Italianate arch in the decorative window cap. The eaves are also decorated with some brackets.

Though it is hard to pinpoint an exact date of construction for this house, it can be determined that the home was built after 1878. The city directory from that year and the Hopkins City Atlas of Halifax, opens a new window indicate that there were no structures on the building lots in this area at that time.

The lineage of this house becomes difficult to trace partially due to adjustments in the civic numbers. For example, in 1900, the civic numbers on the west side of Robie Street between Cunard and Charles Streets ranged from 274-312. By 1910, they ranged from 494-562. Small adjustments continued to be made up until the mid-20th century. The occupants of the house are also difficult to trace. City directories indicate that the house had many different people living in it, some changing year after year. It appears the occupants who lived in the house for the longest were Dr. Edward Thomas Granville and his wife Isabel (Greta), who owned the home for approximately twenty years before it was converted into apartments in the 1960s.

1460 Oxford Street is a totally different example of the Italianate style. A beautiful staircase leads to the front door, which features a wonderfully decorated frame and surround. The matching bay windows on each side of the entrance give it the classic three-bay façade and the arched windows on the upper floor are very happy to see you indeed! The cherry on top of this house is the return of the square tower, which also sports rounded windows to match the second floor.

This property - known as Oakville - once belonged to Levi Hart, a commission merchant from Guysborough. An advertisement for his business Hart, Levi & Son, Limited, from the 1905 city directory states that Hart dealt in the exportation of dry and pickled fish and the import of salt, molasses, and other West India products. The company also acted as a wholesale merchant for flour, oats, and animal feed (p. 294). After Hart's death in 1907, the home was owned by Edmund P. Allison, a barrister with an office on Granville Street. By the mid-1920s, the estate was purchased by Dalhousie University thanks to a donation from former Canadian Prime Minister R. B. Bennett. It is now the President's Residence for Dalhousie University.

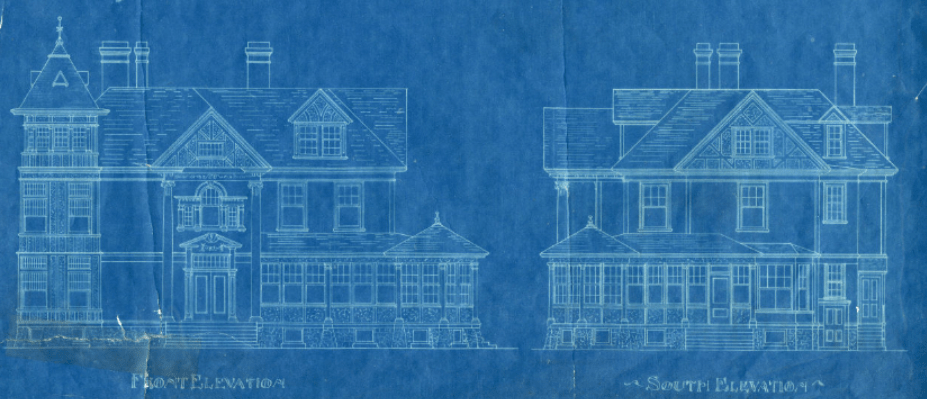

Second Empire (1855-1900)

This style of architecture was the height of trying to keep up with the Joneses.

In the 1850s, Emperor Napoleon III was ruling France. While on the throne, he decided to build an expansion on the Louvre Palace, and his architects looked to the French Renaissance for inspiration. This resulted in a very distinctive roof style, large windows, elaborate decorative elements in both stone and iron, statues, gardens, and more.

And the people LOVED it.

They loved it so much they wanted to bring it home with them. Second Empire architecture began finding its way into the lives of everyday people as they attempted to live a high life like Napoleon III.

How do you spot a Second Empire home?

Like the Emperor himself, Second Empire style has a unique crown on its head. The roofs of Second Empire homes have very distinct construction: a very low-pitched - or sometimes even flat - roof that has a very steep pitch at the eaves. This is called a Mansard roof, named after François Mansart, who used this style in the 1630s. As this style of architecture progressed, the pitch at the eaves went from mostly straight in older houses to having a distinctive curve in newer designs.

Another frequent feature of a Second Empire home is an arched cap above the front door, with matching trim around the windows. Bay windows — both one and two stories in height — are often present, and the additional windows in the home tend to be quite large compared to the standard. In more complex construction, the square tower once again makes an appearance.

Where can I find one?

Due to the distinctive roof and the popularity of the Second Empire style, these stunning homes are pretty easy to spot.

22 Dahlia Street is a lovely version of a simple Second Empire design. The house is lightly decorated with carved wooden trim around the windows and fretwork and brackets on the frieze board. The single-story bay window compliments the front door with matching elements, and the telltale Mansard roof gives the impression of Napoleon-like grandeur. Make sure to take note of the curve at the eaves.

Prior to 1920, it does not appear that the homes on Dahlia Street were given civic numbers in the city directories. They were simply listed as "Dahlia Dart.” This makes the history of this home a little more difficult to trace. However, on the 1878 H. W. Hopkins City Atlas of Dartmouth, it appears that the land on which the house sits was owned by B. Russel. This is confirmed by a directory from 1881 that lists Benjamin Russell as living on Dahlia. Russell was a local lawyer, politician, and academic who eventually became a judge. It could be argued that Russell's most notable trial was the manslaughter case against Francis Mackey, the pilot of the ship Mont Blanc that was involved in the Halifax Explosion. Ultimately, Russell determined that there was insufficient evidence for the charge and released Mackey.

By 1900, it appears that Russell had moved from Dahlia Street to Mount Pleasant, and his brother John George Thomas Russell had moved to Dahlia. Assuming J. G. T. Russell and his family resided in the same house, the home wasn't issued a civic number until 1922, when it became 22 Dahlia Street.

1173 South Park Street is a more elaborate version of Second Empire architecture. The home has the quintessential Mansard Roof, but it is decorated with a lot of Italianate influences. For example, the windows have a rounded shape with matching trim; the square tower, while subtle, sits in the middle of the classic three-bay façade and is accented with a small arch built into the cap above the front door that perfectly matches the windows. The additional decorative elements above and below the bay windows, as well as along the eves, give this home character that is pleasing to the eye and also makes it a unique work of art.

Using city directories as a guide, this home was built between 1884 and 1900. Up until the mid-1880s, very few structures are listed on this city block. In the city directory for 1883-1884, only three people are listed as having homes between Arts Street (now Fenwick Street) and South Street: James Gossip, William Ross, and Henry Fidler.

By 1900, the neighbourhood had changed, and some of the civic addresses on South Park Street were reordered. At this time, John Young Payzant was listed as living at 81 South Park Street. This civic number would be consistent until the mid-1960s when it became 1173 South Park Street. Payzant may or may not have built the house, but he was at least living in it at the turn of the century. Payzant was a barrister originally from Falmouth, Nova Scotia. He died in California in 1920 but was returned home to be laid to rest.

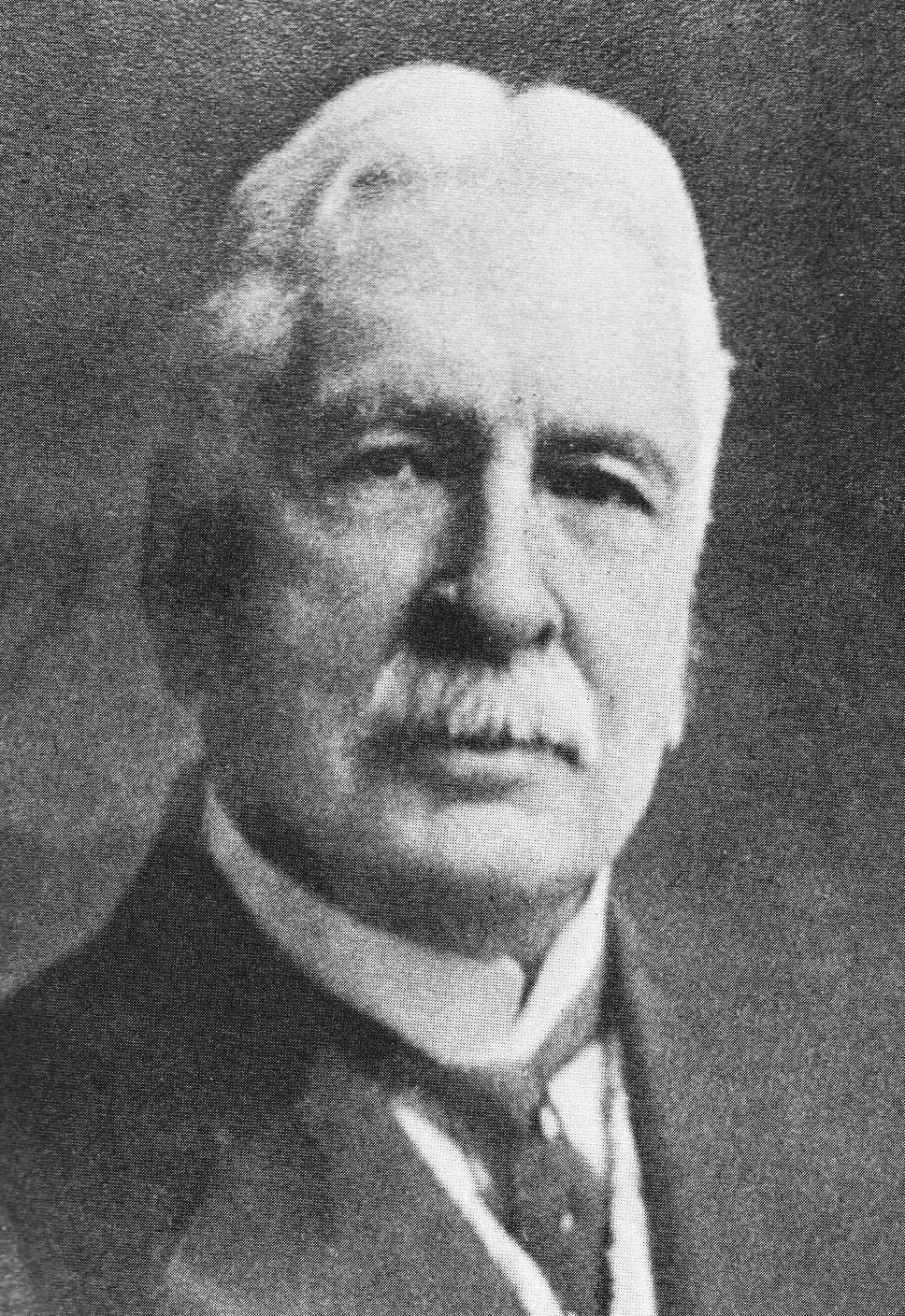

1390 Thornvale Avenue is an extravagant example of a private Second Empire home. This large house overlooking the North West Arm is made of brick and wood. The roof is in the traditional Mansard style, with iron fencing at the top. The upper windows on the third floor have an arch shape that is typical of Second Empire, and the front of the house brings it all together with a square tower and an ornately decorated front door.

Thornvale sits on land once owned by William Pryor, an American loyalist born in New York. After growing up in Halifax, Pryor became a ship captain commanding vessels involved in trade with the West Indies while his brothers handled the business end at home. Around 1800 he returned to Halifax and joined his brothers at their office. In 1816, Pryor purchased a large parcel of land on the North West Arm for £587 (or around £45,805.23, or $76,475.10 today).

By the 1860s, Pyror had passed away, and his land on the Arm was largely subdivided and sold. Around this time, Thomas Edward Kenny, a merchant born to a wealthy Irish family in Halifax, acquired a substantial portion of Pyror's property. It is believed that Thornvale was built by Kenny in the late 1860s. Kenny dabbled in politics throughout his life, but arguably his grandest accomplishment was as president of the Merchants' Bank of Halifax, which later became the Royal Bank of Canada.

The Finishing Lines

These homes are but a taste of the architectural darlings that are right here in our neighbourhood. Whether they are modest or magnificent, these homes are an important element of the landscape in which we live. Though they stand in stoic silence, they each tell a part of our collective history.

Library Sources

Georgian Halifax, opens a new window

Houses of Nova Scotia, opens a new window

A Nova Scotian's Guide to Built Heritage, opens a new window

Pride of Home, opens a new window

Researching A Building in Nova Scotia, opens a new window

Sketches of Old Dartmouth, opens a new window

Halifax and Dartmouth City Directories, various years

Sources

2534 Oxford, opens a new window

Ancestry Library Edition, opens a new window

Canada's Historic Places: Scott Manor House, opens a new window

Conrad, John, Nova Scotia Archives, opens a new window

Flying Buttresses, Britannica, opens a new window

Grigor House, Nova Scotia Archives, opens a new window

Grigor, William, Dictionary of Canadian Biography, opens a new window

H. P. Hopkins Map of Dartmouth, Nova Scotia Archives, opens a new window

Inflation Calculator, opens a new window

Italianate Architecture: From Italy to America, opens a new window

Kenny, Thomas E., opens a new window

Payzant, John Y., Find a Grave, opens a new window

President's Residence, opens a new window

Pyror, William, opens a new window

Scott, Joseph, opens a new window

Scott Manor House, opens a new window

The Seven Key Characteristics of Gothic Architecture, opens a new window

So What Is Dutch Colonial Style, Anyway?, opens a new window

Talk like a pro with these key home exterior terms, opens a new window

Thornvale, Nova Scotia Archives, opens a new window

A Vision of Regeneration - Thaddeus and Mary McTiernan's house, opens a new window

Add a comment to: Amateur Architectual Adventure! – Style and Story in HRM