Written by Vicky, staff member, Halifax Central Library, opens a new window

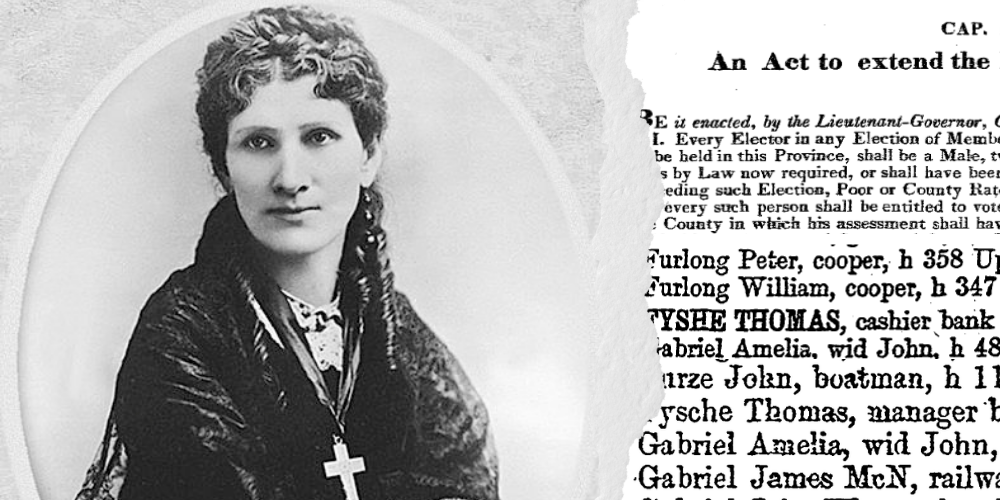

Some people are more fiction than fact, and that is particularly true of Anna Leonowens.

Some may know her as an educator and social activist, while others may know her only through song, as her life story was the inspiration for the Rodger and Hammerstein musical, The King and I, opens a new window. No matter how you know her, one thing is certain: Anna Leonowens lived a life that blurred the lines between the real and the fabricated. A royal tutor, writer, and a world traveller, Anna eventually found herself in Halifax, where she insisted on making a lasting impression. Let’s take a moment to learn about Anna, and how she left her mark on the city.

A very British beginning

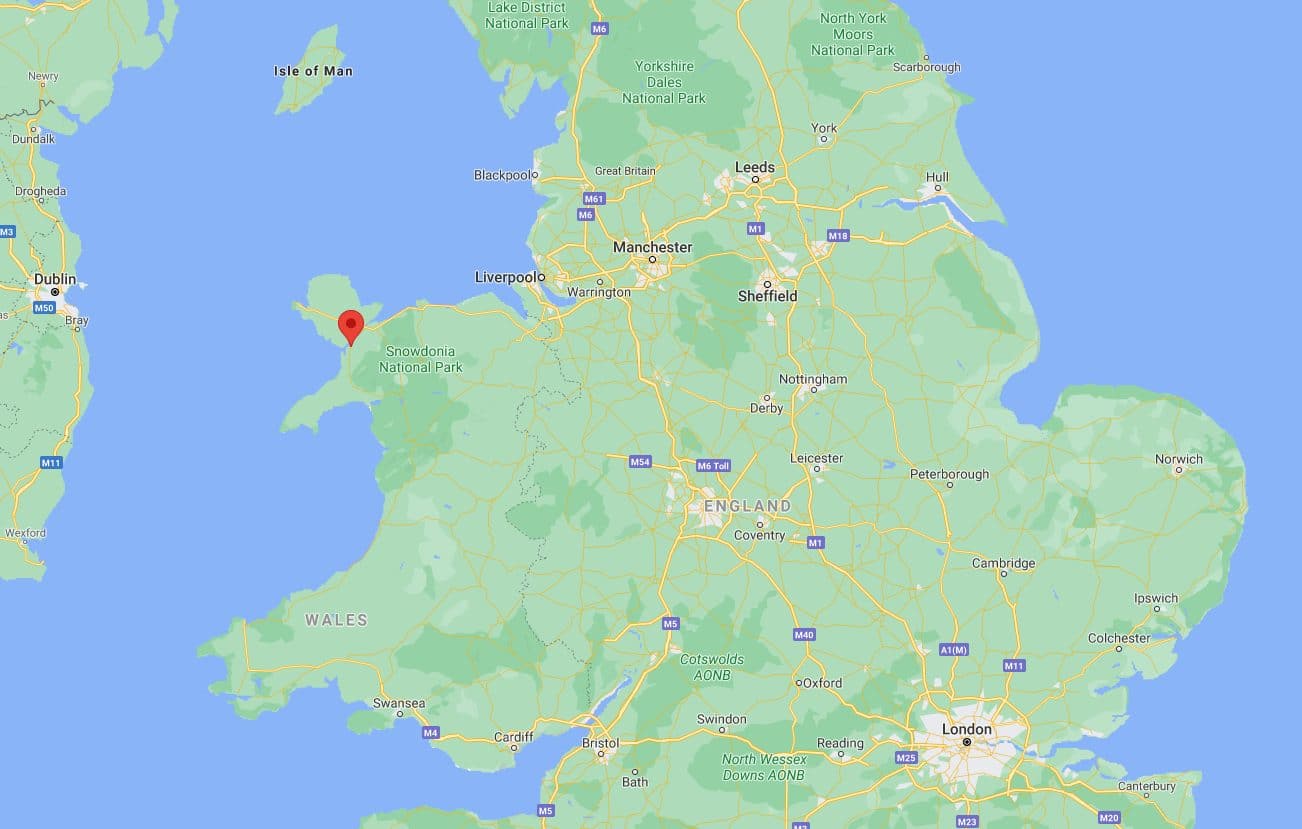

Anna was born on November 5, 1834, in the scenic town of Caerarfon, Wales. Her father, Captain Thomas Maxwell Crawford, and mother, Mary Ann Glascott, lived a high-class life:

Carnarvon was a good place to begin life… There was fresh wind from the sea, and ships coming and going in the blue and spacious bay… Reared in this land of elf and Merlin, it was not strange that Anna Harriette Crawford remembered vividly all her life how as a child she had posted letters in trees to fairies… Nor was it strange that she carried away from it through the years a profound love of freedom, a deep religious faith, a courage and a pride that never deserted her.

— Landon, Anna and the King of Siam page 4.

When Anna was six years old, her father was sent to India with the army. Her mother travelled with him to India, leaving Anna at home in the care of a relative. Within a year, news reached Anna that her father had died in combat, and that her mother was going to stay in India. Years passed, and at the age of fifteen after having completed her schooling, Anna too made the journey to India to rejoin her mother and newly wedded husband. This would be the beginning of her long and exciting life—at least, that’s how author Margaret Landon tells the story in her book, Anna and the King of Siam, opens a new window.

Unfortunately, this portrait of Anna as a fresh-faced, young girl from Wales arriving in an exotic land ready for adventure, is simply not true. And that’s not strictly Landon’s fault–when asked about her childhood, this was more or less the story Anna told. The reality, however, was very different.

“The most important thing in life is to choose your parents” – Anna Leonowens

The truth, later confirmed by government records, is that Anna Harriette Edwards Leonowens was not born in Wales, but in Ahmednagar, India. The actual date of her birth is somewhat uncertain—with various sources claiming slightly different dates—but all of them estimating November of 1831. Her father, Thomas Edwards, was an enlisted man with the rank of Sergeant in the Royal Corps of Sappers and Miners—a part of the military work crew. If enlisted men were considered to be of low social status, the Sappers and Miners were lower still. Her mother, Mary Anne Glascott, was of mixed Indian and British heritage, and likely an army brat, just as her daughter would be.

In July of 1831, a few months before she was born, Anna’s father passed away leaving herself, her mother, and older sister, Eliza, in a difficult position. Widows and families were not able to stay with the regiment for more than a few weeks after the head of their household died. Facing the prospect of being homeless with two children to feed, Mary Ann married Patrick Donohoe, a Second Corporal in the Corps of Engineers, in January of 1832. Mary Ann and Patrick would go on to have several children, and the next few years were spent living a traditional military life, with the family frequently on the move.

Though Anna would have no love for her life as an army child, it did provide her with a good education. Attendance to the garrison school was mandatory, and Anna began lessons in reading, writing, and arithmetic at age four. Through her education, she would study British History and literature, but what intrigued her most was the study of Indian languages and culture. By age fifteen, Anna’s formal education was officially complete. As a woman of her time, she had very few choices when it came to what she would do with her life, and her stepfather was eager to marry her off. However, Anna refused to be married to someone of her stepfather’s choosing, and managed to fend off possible suitors until falling head over heels for Thomas Louis Leon Owens, a military Pay Clerk. They were married on December 25, 1849, and, if their letters to one another were any indication, madly in love.

Thomas and Anna would have four children: Selena Louisa and another unnamed child, both of whom sadly died in infancy, as well as Avis Annie Connybeare and Louis Thomas Gunnis. It is here where Anna’s story takes a tragic turn. In the late 1850s, her husband Thomas dies suddenly of a heart attack, or possibly by heatstroke. Like her mother before her, Anna was left alone with her two children and no means of support. She had the option of remarriage, but in the words of Leslie Smith Dow, author of Anna Leonowens: A Life Beyond the King and I, opens a new window: “Marriage may have made her life easier in the short term, but it would close forever the door to freedom she saw opening before her” (Page 5).

The benefit to being alone, however, is that no one can prove you wrong. Knowing her position in society was dismal and her prospects were few, Anna took advantage of her misfortune and rewrote her life: her father the Captain, her mother the Welsh maid, her high-class upbringing and education; even her beloved Thomas jumped to the rank of Major; her children found a new birthplace in England, and they were all granted the new last name of “Leonowens.” With this new identity, Anna and her children travelled to Singapore in 1859—a place where no one knew them—to start their lives over. She began tutoring students to support the family, claiming to have started a small school. Even with her tutoring, it was difficult to keep the family financially afloat. It was perhaps more good luck than good management that brought her to the attention of Tan Kim Ching, an agent in Singapore to King Mongkut, ruler of Siam (now Thailand). The King was looking for a proper British lady to be a governess to his children, and it just so happened that the new Anna was the perfect fit.

Anna and the King

In 1862, Anna and her son Louis headed to Siam, while her daughter, Avis, was sent to England to attend boarding school. Having been promised a salary of $150 a month and a house near the Christian missionaries, upon her arrival in Bangkok, Anna was instead told that she would be paid $100 a month, and live near the palace. King Mongkut was very clear in his expectations of Anna, telling her in a letter that she was in no way to attempt to convert his children to Christianity, and that the education of his 67 children, and several of his wives, was to focus on the English language, science, and literature.

According to Anna, the school at the palace took place in a temple: “The floor of this beautiful temple was a somewhat gaudy mosaic of variegated marble and precious stones… In the centre of the temple stood a long table, finely carved, and some gilt chairs.” King Mongkut and the temple priests were initially present, and watched as servants brought in boxes of supplies – pencils, slates, books, etc – but they did not stay.

… Then his Majesty departed with the priests; and the moment he was fairly out of sight, the ladies of the court began, with much noise and confusion, to ask questions, turn over leaves of books, and chatter and giggle together. … It was not long before my scholars were ranged in chairs around the long table, with Webster’s far-famed spelling-books before them, repeating audibly after me the letters of the alphabet.

— Leonowens, “The English Governess at the Siamese Court,” Project Gutenburg.

Anna’s time at court was complicated, to say the least. While she admired many cultural aspects of Siam, like the language and the Buddhist religion, there were many other aspects of which she disapproved. She saw their world through her own lens as a White, Christian woman, and eventually the cultural differences coupled with the sadness of being separated from her daughter became too much. Anna and Louis left Siam after five years at court.

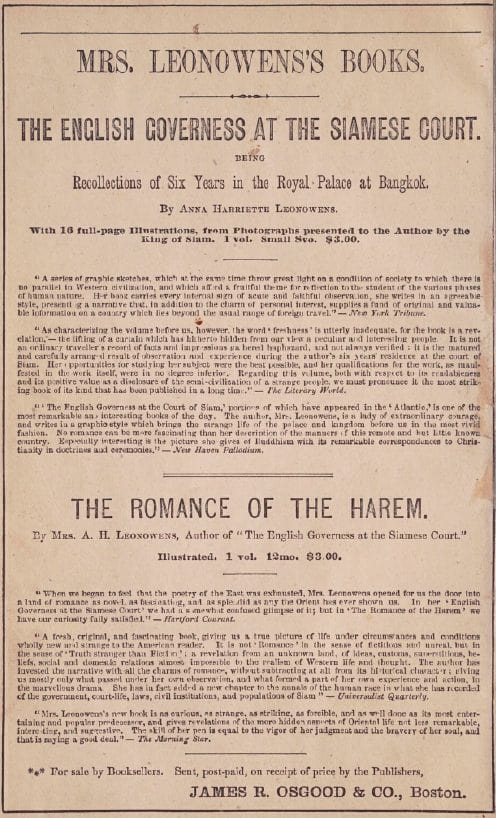

Upon leaving Siam, Anna placed Louis in an Irish boarding school to continue his education and reunited with her daughter. She and Avis moved to New York, where Anna began her writing career, detailing her adventures in Siam. She published two books, The English Governess at the Siamese Court (1870), and Romance of the Harem (1873). Though these books might have elements of truth, they are now known to be exaggerated and partially fictionalized. At the time of their publication, however, the books were very popular, and Anna went on a tour of both the United States and Canada to promote her works. She also wrote articles for magazines, like Youth’s Companion, a publication out of Boston, Massachusetts.

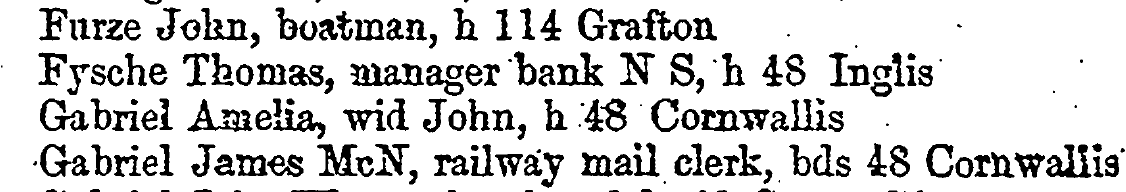

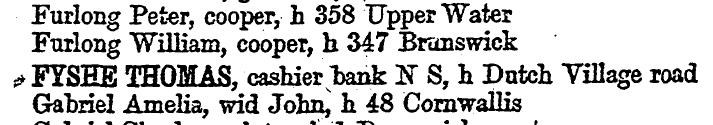

While living in New York, Avis met a man named Thomas Fyshe. Thomas was a banker who was working in New York as a stockbroker, but was later hired by the Bank of Nova Scotia—first in St. John, and then as the General Manager in Halifax. He and Avis exchanged many letters, and eventually, Thomas wrote to Avis professing his love: “I fell in love with you at first sight.” He returned to New York in the early days of 1878 to propose, and the two were married within six months. Thomas wanted Avis to move with him to Halifax, and welcomed Anna to join them. As soon as the honeymoon was over, the family began a new adventure on Canada’s East Coast.

At home in Halifax

Anna arrived in Halifax in September of 1878, but didn’t settle for long. She received offers to continue giving lectures in the U.S., to teach at the Berkeley School for Boys in New York, and to travel to Russia to write once again for Youth’s Companion. She accepted all of these invitations, leaving Avis, Thomas, and their growing family in Halifax. In 1882, Youth’s Companion offered Anna a position as editor. It was an incredible opportunity, but her desire to be with her grandchildren outweighed her professional ambitions. She returned to Halifax, and this time she planned a more permanent stay.

In 1883, the Fyshe family moved into a new home on Dutch Village Road, which they called Sunnyside. During this time, Anna acted as a traditional matriarch, running the household and providing a rigorous education to her grandchildren. Susan Morgan, author of Bombay Anna: The Real Story and Remarkable Adventures of the King and I Governess,, opens a new window described late 19th Century Halifax as:

… a fishing port, and not particularly pretty in its architecture and layout. In character it was an odd combination – at once semirural, isolated, filled with rugged characters, lacking in facilities, lacking many of the comforts and pleasures of urban culture, and yet socially rigidly hierarchical. … She [Anna] noted that ‘everyone here has been most courteous to us. Still, it is odd to see the airs which the English give themselves here; the class distinctions which are maintained.’

— Morgan, Bombay Anna, page 188.

Having both grown up in strict class systems, Anna and her son-in-law recognized that it was their education that allowed them to rise above their stations, and insisted on the best schooling possible for the Fyshe children.

While at Sunnyside, Anna also continued her writing career. She crafted a third book, Life and Travel in India: Being Recollections of a Journey Before the Days of Railroads, as well as articles for the magazine Wide Awake, which would eventually form a fourth book, Our Asiatic Cousins. But her writing and her family were not enough. Anna wanted to change Halifax for the better. She began by establishing a book club, and a Shakespeare club, but she had bigger plans in mind.

At her core, Anna was a feminist. She believed that women were capable of more than the traditional roles that had been set out for them—she had proven it to be true. And so Anna and a group of local women began petitioning for a school in Halifax that would focus on fine arts education, and would give ‘a higher artistic value to all the various branches of mechanical and industrial arts’. In her book, The Nova Scotia Nine: Remarkable Women, Then and Now, opens a new window, Joanne Wise writes: “Anna and others envisioned the school as a centre for excellence, a training ground for skilled artisans, and an economic engine for the region. She was particularly interested in improving the employability of women” (p. 13). In 1887, their hard work paid off. As a part of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, the Victoria School of Art and Design was born. Though the school moved a number of times in its early years, it eventually found a home on Argyle Street, where it remained for fifty-four years. The Victoria School would later become the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, or NSCAD.

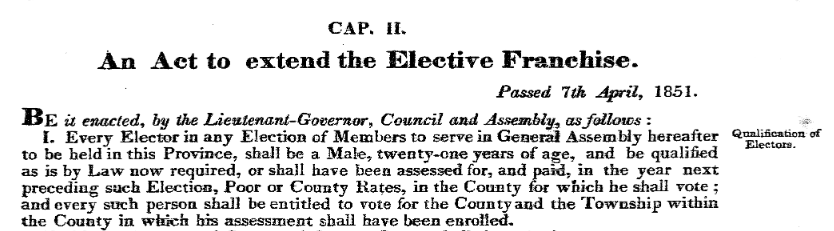

Anna was also a major player in the Local Council of Women, which was formed in 1884. This group of women, which included Edith Archibald, Eliza Ritchie, Agnes Dennis and May Sexton, worked tirelessly to support the rights of women and children in Halifax. Their work included collaborations with The Nova Scotia Red Cross, The Halifax Playground Commission, The Halifax Victorian Order of Nurses, the Anti-Tuberculosis League, and many more. The Council would work to improve the education of children in Halifax, and the conditions for women at Rockhead Prison, but one of their main focuses was gaining the right for women to vote. At a meeting of the Dominion Enfranchisement Association (which would later become the Canadian Suffrage Association), Anna stood in front of the crowd and stated: “…women have not only proved their capacity for governing great nations, but have shewn wonderful capacity for affairs and proved herself to be a true helpmeet and coworker, instead of a servant and plaything of a man!” She went on to state that since women were unable to vote, they should stop paying their taxes as they had no say in how the money was spent. Coupled with the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, the Local Council of Women submitted thirty-four petitions and supported six suffrage bills.

As Anna’s grandchildren grew, the family realized there was a need for some extended education. Ann, her oldest granddaughter, was particularly adept at the piano and it was decided that she should attend school in Germany to further improve her skills. In 1888, Anna, Avis, and all of the grandchildren travelled to Europe, leaving Thomas behind. They remained in Germany for five years, where Ann was not the only person getting additional education. Anna herself enrolled in a Sanskrit course at the University of Leipzig—she already spoke the language, but was hoping to brush up her skills. In 1893, the family returned to Halifax, and reunited with Thomas at their new home at 235 Pleasant Street. Anna returned to her work with the Victoria School and the Local Women’s Council, and became president of the Women’s Suffrage Association in 1895. However, in 1897 Thomas was offered the position of General Manager for the Merchant’s Bank of Canada in Montreal. The family was on the move, and Anna’s time in Halifax was over.

All good things…

Anna’s life in Montreal was marked by tragedy. In 1902, her daughter Avis became ill with food poisoning and died. In 1908, Thomas suffered a stroke, and became bound to a wheelchair—he died three years later. Anna pushed through these losses by focusing her energy on supporting her grandchildren, ensuring they all received post-secondary education. Sometime after Thomas’ death, she too would have a stroke, which would completely blind her and leave her mostly bedridden. Under her granddaughter Avis’ care, she lived out the end of her days at home before passing away on January 19, 1915.

Anna’s life was in many ways forgotten until 1944 when Margaret Landon published her book Anna and the King of Siam, opens a new window. The book, based on Anna’s own writings, became a best seller:

Landon’s Anna was the very gentlewoman whom Anna, so long ago in Singapore, had envisioned and then declared herself to be. Margaret read Anna’s books and was entranced by what she saw as the nobility of Anna’s experiences. Margaret then invented an identity and a life for Anna that, to Margaret’s surprise, transformed this long-dead woman into a major icon of twentieth-century American culture.” (Morgan, 207).

The book would go on to inspire the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, The King and I, opens a new window, which would later move from the stage to the big screen. As a result of Landon’s retelling, Anna is now known to people all around the world.

So what?

Anna’s time in Halifax was spent making the lives of the people who lived here better. She fought for civil rights, and brought a level of culture and education to Halifax that had not been seen before. In her honour, NSCAD established the Anna Leonowens Gallery in 1968 as a public exhibition space. The Gallery has three locations in the City, and focuses on “…professional exhibitions by curators and professional artists alongside NSCAD MFA Thesis and BFA graduating solo exhibitions… a third space focus(es) on performance art, relational aesthetics and art happenings.” What Anna didn’t realize while she was alive, is that a person does not need to change their past to make a difference. She believed she needed to be viewed as upper-class and wealthy in order to be seen and heard, but the power and the words to make change were always within her. It was her confidence and courage that gave her strength and the ability to fight for a better world.

If you would like to read some of Anna’s books, you can find them at Project Gutenberg, here, opens a new window.

Library Resources

Atlantic Insight, “From Siam to Halifax”, August 1988, page 18-20

The Beaver, “Anna, the King, and I”, December 2008/January 2009, page 54-55

“Fighting for Women’s Rights: The Extraordinary Adventures of Anna Leonowens” by Moushumi Chakrabarty – 823.8 L585c

“Witness to a New Nation: 150 Nova Scotia Buildings That Saw Canada’s Confederation of 1867” by Heritage Trust of Nova Scotia

“Anna and the King of Siam” by Margret Landon – RED 921 L585L

“Mrs. Leonowens” by John MacNaughton – REF 921 L585m

“Bombay Anna: The Real and Remarkable Adventures of the King and I Governess” by Susan Morgan – 959.3034 L585m

“More History with a Twist” by Bruce Nunn – 971.6 N972m

“Anna Leonowens: A Life Beyond the King and I” by Leslie Smith Dow – 921 L5855

“The Nova Scotia Nine: Remarkable Women, Then and Now” by Joanne Wise – 920.720716 W812n

Vertical File - BIOGRAPHY

“Death in Montreal of Former Halifax Lady”, Chronicle Herald, January, 23, 1915

“Sifting Facts From Leonowens’ Fancy”, Chronicle Herald, February 28, 1992

“Anna in Halifax”, Chronicle Herald, April 25, 1999. C4 and May 2. 1999

“Leonowens Gets Royal Treatment”, Chronicle Herald, September 19. 2012, A1-A2

Online Resources

The Canadian Encyclopedia - Anna Harriette Leonowens, opens a new window; Nova Scotia College of Art and Design University, opens a new window; Women's Suffrage in Atlantic Canada, opens a new window

Historica Canada - Women's Suffrage in Canada, opens a new window

Google Maps , opens a new window

Library of Congress , opens a new window

The Local Council of Women Halifax , opens a new window

The Nova Scotia Archives , opens a new window

Nova Scotia College of Art and Design , opens a new window

The Nova Scotia Legislature, opens a new window

Add a comment to: Anna Leonowens and the City of Halifax: A Brief and Not at All Definitive History