By Aaron, staff member, Halifax Central Library

By Aaron, staff member, Halifax Central Library

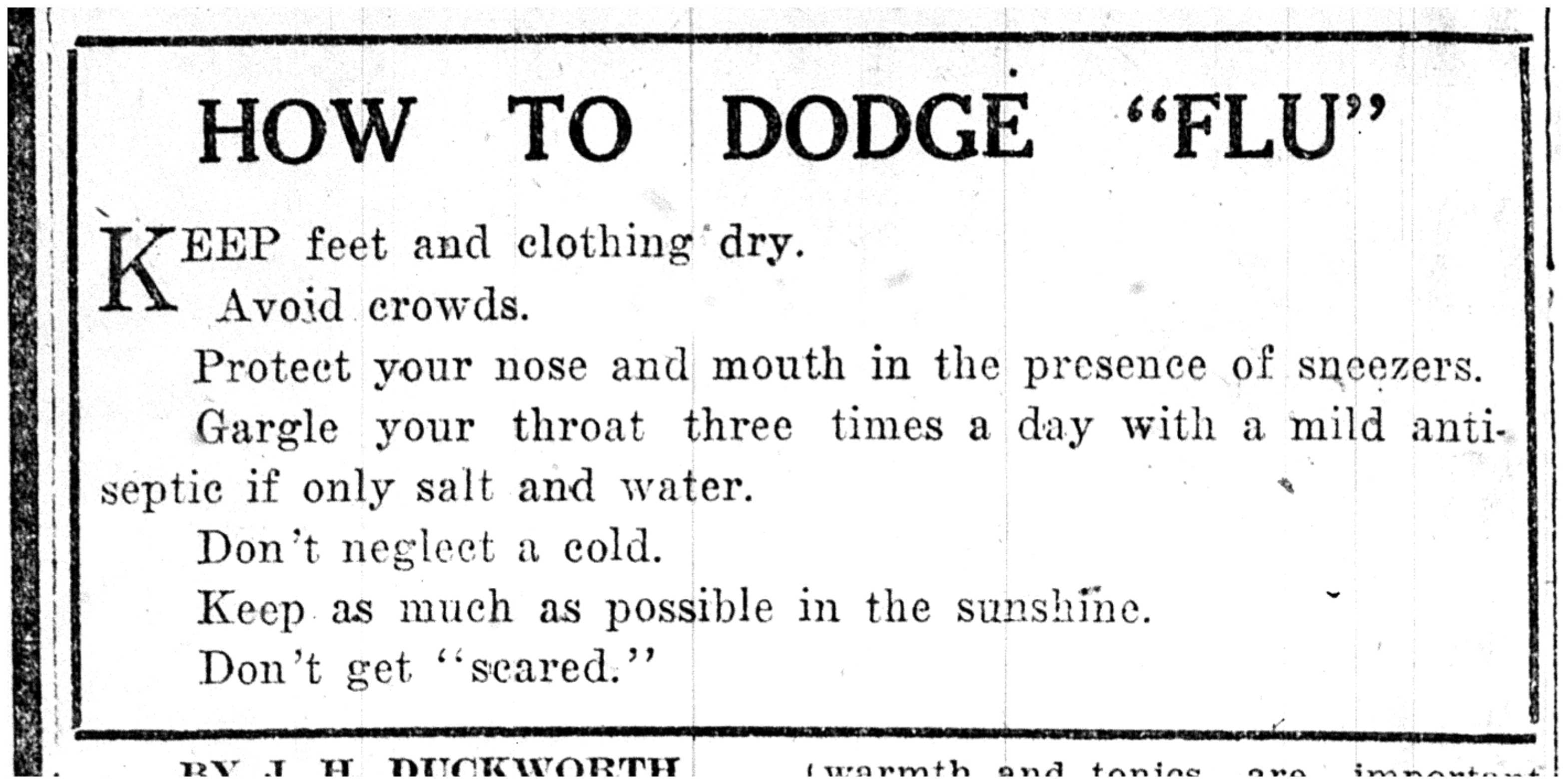

How to Dodge "Flu"

By the end of Summer 1918, Halifax and Dartmouth were still rebuilding after the deadly Halifax Explosion that claimed nearly 2,000 lives and devastated both communities. In all appearances, the First World War was slowly drawing to a close, but this bustling military port on the East Coast was still busy with comings and goings of maritime traffic. Little did anyone foresee the arrival of a deadly illness that would kill more than 50,000 people across Canada before the end of the decade and shut down much of public life in Halifax and Dartmouth for the entire month of October.

Deadly traveler

According to the Canadian Encyclopedia, opens a new window, the pandemic known as the “Spanish Flu” developed first in Asia, but outbreaks at military bases in the USA, Spain, and war-torn Europe caught the public’s attention in the spring of 1918. As a particularly strong viral infection, the Spanish Flu did not discriminate between the old and the young. A healthy adult would die within 48 hours once the infection swiftly became bacterial pneumonia, and with no antibiotics or vaccines available, there wasn’t much that could be done.

A glimpse into the past

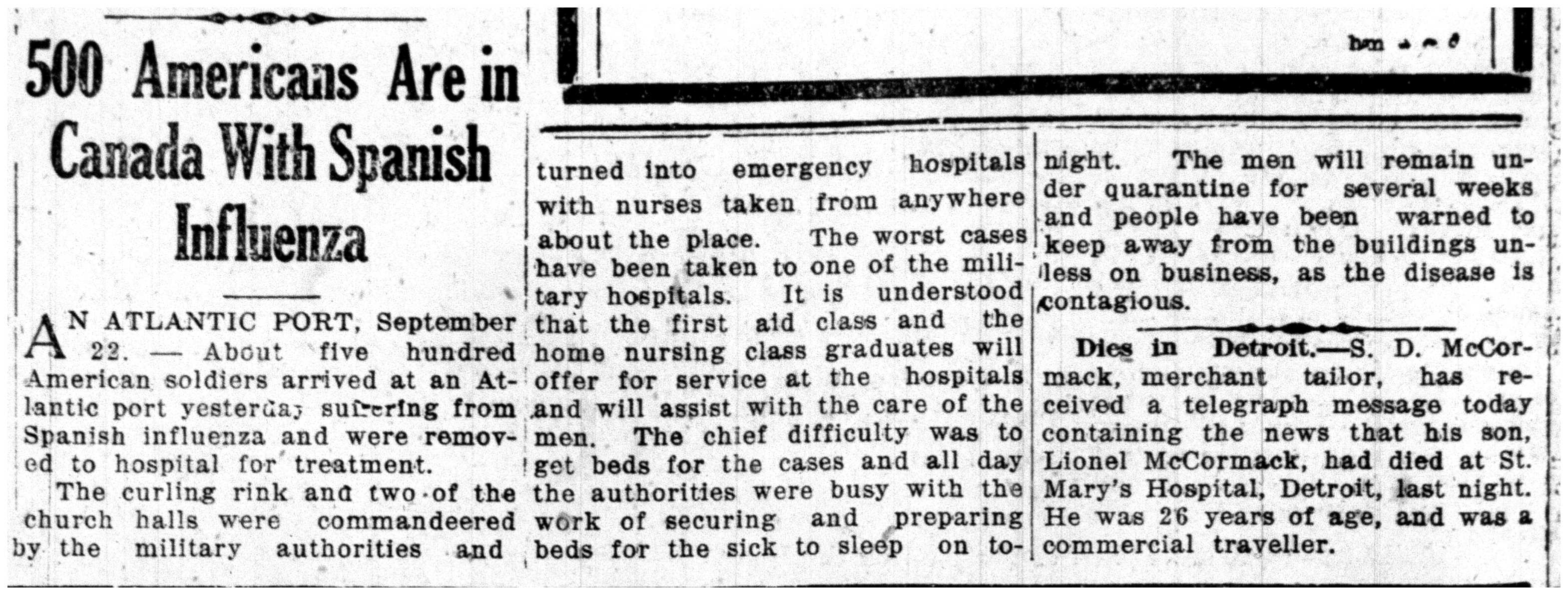

An interesting way of exploring how the Spanish Flu arrived in Nova Scotia is to look at the local daily newspapers, like the Halifax Evening Mail, available at Halifax Central Library’s Local History Room. While news of the pandemic trickled in from Boston, on September 21, a report from “An Atlantic Port”, (Sydney, Nova Scotia) raised the alarm province-wide that over 500 American soldiers had arrived sick and were in need of hospitalization. Over the next 2 months, cities like Sydney, Halifax, and Dartmouth rushed to control both the spread of the disease, and to provide proper care for the victims.

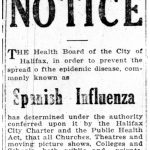

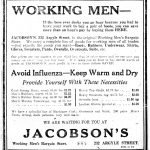

Featured daily in the newspapers were some of the following efforts:

(click images to expand)

- Halifax and Dartmouth’s Boards of Health ordered all public gathering places, including churches, theatres, schools, and restaurants to reduce open hours or to close completely. This cautionary measure provoked anger from business owners, and discontent from late-night industrial workers.

- On the flip side, some businesses saw opportunity. One men’s clothing stores advertised their products would help avoid the influenza by keeping you warm and dry. Unproven “miracle cures” like drinking pasteurized milk from sterilized bottles and caps as a resistance against the flu were advertised.

- The general public even had their own ideas on how to stop the spread of disease, including burning sulphur on street corners.

- Boston and the State of Massachusetts suffered greatly from the pandemic. Less than a year after the Halifax Explosion, Halifax repaid Boston in kind by sending available local doctors and nurses to help. Samuel W. McCall, Governor of Massachusetts, sent a telegram offering thanks for the assistance: “This act of yours typifies the spirit of Halifax and Nova Scotia and serves to bind together with closer ties this commonwealth and your province.”

- As the Spanish flu spread, newspapers published daily reports, listing new cases, infected occupant addresses, and sadly, deaths. Both Dartmouth and Halifax opened hospital beds at the quarantine facility on Lawlor’s Island, the Cogswell Street Military Station Hospital, unused wards in Victoria General Hospital, and at Greenvale School, but they also quickly built a facility in Willow Park. Funerals had to be performed quickly, with no public attendance.

By the end of October, the number of cases had peaked and then just as quickly, the pandemic seemed over and both cities began to return to normal. However, walking through Halifax and Dartmouth, it must have felt like a weary, strange place; twin cities recovering from the Explosion, enduring the fourth and final year of a world war, and now struggling to contain a fast-striking disease. On November 5, all public health restrictions were lifted and life began to return to normal, just in time to celebrate the end of World War One on November 11, 1918.

More resources

Of course, there’s so much more to the Spanish Flu story in Nova Scotia.

Some other sources to explore:

- Central Library’s Local History Room has a clipping file called “Public Health (Diseases)” where you will find over one hundred newspaper clippings from the Halifax Evening Mail.

- “The Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919: The Nova Scotia Experience” in the Heritage Trust of Nova Scotia’s newsletter, The Griffin (September 2009, Volume 34, No.3, pp. 9, 22).

- “Home Sick”, by Paul A Erickson in Canada’s History (April-May, 2011, pp. 50-51).

Add a comment to: The History of Spanish Influenza in Halifax