Written by Guest Blogger, Kate Foster

OTHELLO POLLARD, To his Friends and the Public, more especially to gentlemen of delicate taste, and well-educated appetite, offers the rich Viands and various Luxuries, exotic and indigenous, of his CLASSIC HOTEL—or ATTIC BOWER, in which he flatters himself, the Entertainment will at all times be found, polite in style, and excellent in quality; his guests select and fashionable; and his own humble services sedulous and acceptable.

(Boston Gazette, opens a new window, June 13, 1803)

Othello Pollard was once a well-known African American chef and caterer who lived the latter part of his life in Halifax and Dartmouth. Among the earliest fine-dining restaurant owners in the United States, Othello was also Halifax’s first known Black restaurant owner. Born about 1758, he achieved culinary renown in Boston. He moved to Halifax between 1806 and 1812 and, after some hardships, died in poverty in 1844. Buried in downtown Dartmouth in an unmarked grave, his achievements are largely unknown and mostly forgotten. Othello deserves to be remembered for his pursuit of excellence and as a pioneer of Black entrepreneurship in Halifax.

His short but successful career in Boston has been written about by several American authors. His culinary creations, and the literary descriptions that often accompanied them, attracted attention and praise during his lifetime. Locally, he was written about by Dartmouth historian John P. Martin, who found accounts of Othello in The Acadian Recorder, opens a new window, a Halifax newspaper. Othello also appears in other local records—church and property records and at least one census return.

Although much is unknown about Othello, a review of his life reveals he was many things: enterprising, intelligent, witty, entertaining, and determined. Like his Shakespearean namesake, Othello’s life was tragic. He endured fires that destroyed his livelihood. He lived and worked in places where racism against Black people was ever-present. As a “character” about town, White writers wrote about him with a mixture of admiration and condescension. Although “exceptional” and regarded affectionately, he was still a Black man in early-1800s Boston and Halifax, where the social, legal and financial position of Black people was often precarious.

Boston career

It is unknown if Othello was born free or was born in slavery and then became free. Before his time in Boston, Othello lived in Philadelphia, where, in 1794, at 36 years of age, he was a member of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, the first Black Episcopal congregation in the United States. Founded “to foster personal and religious freedoms and self-determination” for Black people, the Church’s philosophy may have provided a foundation for Othello’s lifelong perseverance and industry. He would also have been influenced by the cosmopolitan culture of early Philadelphia, known for its African and Caribbean foods and creole cooking.

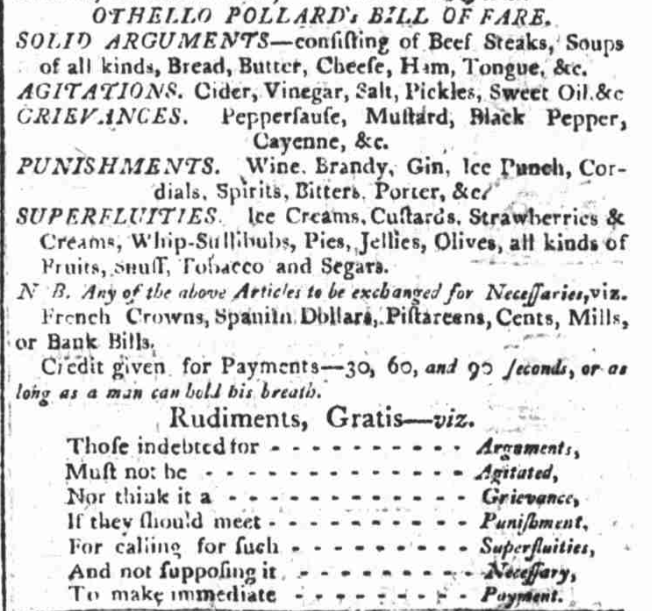

By 1799, Othello had moved to Boston, where in December of that year, he married Eupha Brown. Between 1800 and 1802, he sold food to Harvard College students and catered class events such as commencement. He also had a fine food shop near the Boston Common, opens a new window. Othello suffered a devastating setback when a large fire, started accidentally in a neighbouring building, destroyed his shop in January 1803. He had been a tenant in the burned building and had to start his business anew. Several months after the fire, Othello found another location near the Common and opened his Classic Hotel restaurant. He often advertised his restaurant, goods, and services with clever handbills and announcements.

Newspaper reports and other writings offer a glimpse of Othello’s various talents. He was known for creating and delivering both funeral and party invitations. One newspaper columnist suggested he was also a talented singer. An entertainer with a flair for the dramatic, he used novel ways to promote himself. He once imported a live leopard from Bengal and charged a fee to view it at his shop.

Othello’s main competition, and inspiration, was Julien, a famed Black chef from France, thought to have opened the first fine dining restaurant—Julien’s Restorator, opens a new window—in Boston and the US in 1793. The two men knew each other, had different specialties and were said to have had mutual respect.

Othello became famous for culinary excellence and creativity at Harvard and throughout Boston, known primarily for his mixed drinks and desserts (such as cakes, tarts, and cheesecakes) and as a superior host. His culinary skill was immortalized in poetry and prose by students and columnists. It was even mentioned in an 1805 letter from John Quincy Adams to his brother, sons of the 2nd President of the United States. Recounting a visit to Philadelphia, Adams wrote that friends had entertained him:

…with a banquet of recent literature, which after the famine of a Congressional Session was more grateful to me, than all the delicacies of sensuality that human invention has devised from the days of Apicius, to those of the great men of Julian and Othello Pollard.

In 1805, Othello moved again and opened a third venture, a Coffee-House on Congress Street across from the Boston Gazette office. His menu included “real Green Turtle Soup,” a sought-after dish made popular by Julien. Othello’s Coffee House did not last long; in December of 1806, the building that housed it was for sale.

How did Othello accomplish so much in Boston and acquire the knowledge and resources to start his business? David S. Shields, who has written the most detailed portrait of his life, opens a new window in Boston, notes that Othello “had been principal cook and head waiter” for an elite Boston family and became “a large stockholder in the Mechanics’ bank.” Quoting an 1834 source from The New York Mirror, Shields writes that “by the advice and assistance of several of his master’s friends, backed by the warm recommendation of the gentleman himself, he was now the principal of a first-rate refectory….” Othello’s recommendations and connections from his wealthy White employer played a role in establishing himself in Boston, but his drive and ingenuity ensured he was successful. He would not have such connections in Halifax.

Halifax property

After such career heights in Boston, it isn’t clear why Othello moved to Nova Scotia. He did so sometime between 1806 and 1812—when he first appeared in Halifax property records.

Did he follow friends or family, or simply want to start over in a different city? His life in Halifax began with hope but sadly ended in misfortune.

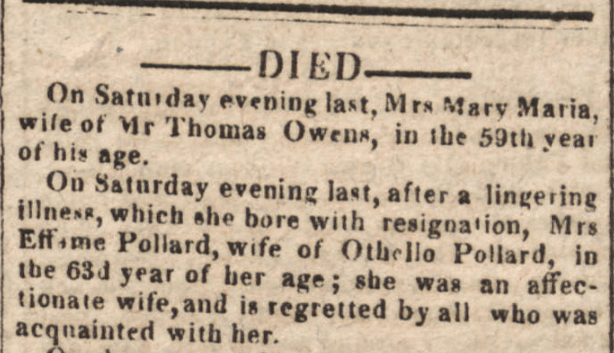

Local property records also list Othello’s wife, Essame, or Essea as she was called. It is assumed that she was the same person as Eupha, whom he had married in Boston. Little is known about her, but she appeared to have been an active part of his business life in Halifax and was a party to most of his property transactions.

Othello was known as a trader in his early days in Halifax. Whether he sold food or other goods has not been recorded. Othello may have saved money while working as a trader. Maybe he had some savings left from his Boston ventures or had attracted local investors. However, he raised funds, and on October 16, 1812, Othello was able to buy a property on Barrington Street for 630 pounds. Shortly after purchasing the property, Othello and Essea sold half of it for 300 pounds and took out a mortgage on the remaining part for 150 pounds. This mortgage was fully paid off in September 1813, indicating that Othello was doing well.

Halifax restaurant

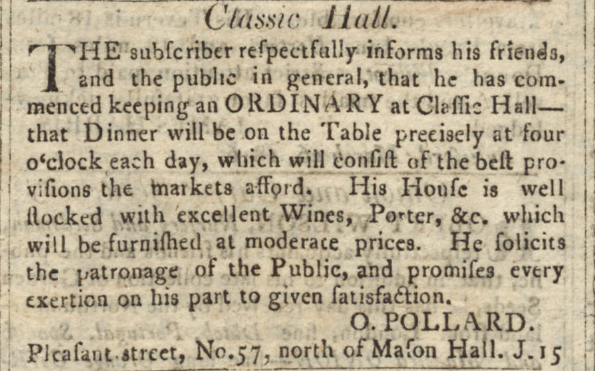

If Othello bought the Barrington Street property with the goal of opening a restaurant, it would take him a few years to accomplish it. In June 1816, Othello launched what appears to be the first Black-owned restaurant in Halifax, called “Classic Hall,” likely named after Othello’s “Classic Hotel” in Boston. Well-positioned at the corner of Blower and Barrington, it was near the first Masonic Hall, a busy centre of civic and social activity in the early 1800s. The advertisement for Classic Hall states it was an “ordinary,” which referred to a restaurant that served a complete meal at a fixed price or served all customers the same standard meal. The ad was noticeably more modest than ads from his days in Boston, as was the style of the restaurant.

Othello’s dining hall was off to a promising start. The ad for Classic Hall ran in the paper for six months. Was it popular or successful? There is no information available to assess this. For at least a year or two, it seemed that Othello was able to operate his restaurant without incident.

Mortgages and foreclosure

Was Halifax a more challenging environment in which to run his restaurant?

In July of 1818, there were signs that Othello’s business was struggling when he took out two new mortgages, one for 300 pounds and another for 70 pounds. By the following summer, he had not made principal or interest payments on either mortgage. Two prominent merchants took over one mortgage and then promptly initiated foreclosure proceedings in Chancery Court. Both mortgages were foreclosed, and the Pollards’ Barrington Street property was sold to a group of well-to-do men in 1820. Why was Othello unable to make any mortgage payments? Was his business failing? Had he suffered some other financial hardship? The public record is silent on these questions.

Another fire

In September 1821, a disastrous accidental fire started in a nearby bakery, destroying the building that housed Othello’s restaurant and almost the entire block of mainly wood houses. The newspaper report of the fire noted that approximately 23 buildings burnt down, 40 families lost their homes, and that “the chief loss has fallen on the proprietors; almost the whole of whom are widows and poor persons, quite unable to repair their heavy misfortune.”

The paper listed “Mr. Pollard” among the owners of houses that burnt down. At the time of the fire, however, Othello’s property had already been sold. It seems likely, that after the sale, he had continued to live and work out of the building as a tenant and that his house was still known as his place, even though he no longer owned it. Despite not knowing all the facts that led to the end of Othello’s restaurant, the result was poverty from which he would not recover.

Other Halifax establishments and tribulations

By 1821, Othello had lost his property and likely all that remained of his business, home, and personal effects. Without any financial resources, he must have struggled to make a living or simply get by. He was 63 years old, and the prospect of starting over again must have been daunting. Perhaps he and Essea hired themselves out, which would have been challenging at his age. When Essea died seven years later, Othello would have found himself alone.

The loss of his wife undoubtedly compounded Othello’s losses, especially as his health began to fail. When he would have been about 73, a long note about him appeared in the newspaper. Requesting donations for Othello, the anonymous writer recounted some details about Othello’s earlier life, including that he had fallen on hard times after having been “burnt out” in Boston and Halifax:

After several vicissitudes, he took up his abode in our Ferry Steamer, and vended sundry “superfluities” and “necessaries” to travellers; during her long rest, he had no means of “getting up the steam” and was obliged to lie by in his cuddy like a bear in winter. The steamer has started once more, but alas! Cakes and ale will not come for bidding from the vasty deep, and Othello’s name is not current at the Halifax Bank. He still wishes to make himself useful, and to earn a crust in his old age, rather than to stoop to mendicity or the workhouse. Some years ago, we recollect, he kept a soup shop, which was of considerable benefit among the poorer classes of the town; his ambition now is to do the same; and if a few of those who knew him in better days, were to contribute a trifle, each, to an old servant, they would set his mill agoing, and smooth the evening of his life.

(Acadian Recorder, Nov. 19, 1831)

The Sir Charles Ogle steamboat ferry between Halifax and Dartmouth was plagued with troubles and provided unreliable and irregular service. Othello’s efforts to make a living selling food on the ferry, another creative venture, failed in such circumstances.

The newspaper writer was likely quoting Othello, but the words “superfluities” and “necessaries” were also a direct reference to the clever ads he used to post in the Boston papers. It is noteworthy that, in Halifax, it appears that Othello’s “soup shop” mainly served the “poorer classes.” His clientele in Boston had been the middle and upper classes.

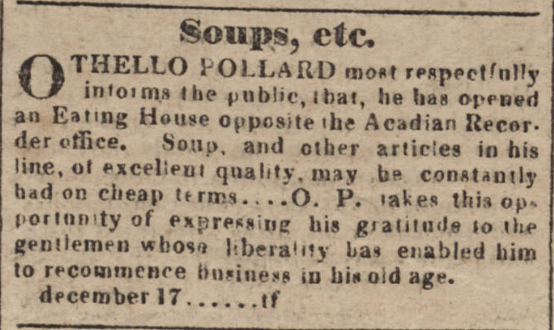

The appeal for donations for Othello was successful. On December 3, 1831, the paper reported that Othello had “recalled his occupation. He intends commencing in a small way, early next week.” On December 17, Othello advertised the opening of an Eating House for the general public across from The Acadian Recorder on Hollis Street. This was, at least, his seventh business venture.

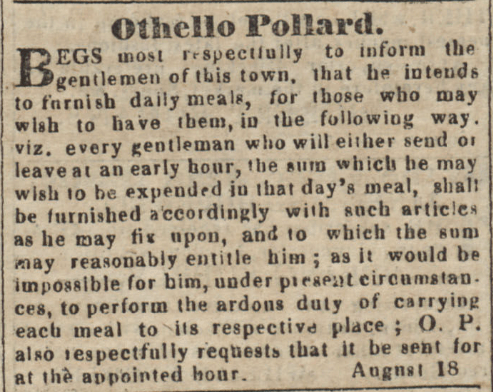

It is not known how long this Eating House operated, but ads for it ran through to at least March of 1832. Later that year, Othello posted a new type of ad, addressed to “the gentlemen” of Halifax, stating he would prepare daily, made-to-order meals for pick-up. Despite his age—about 74—and physical infirmities, Othello continued to seek work.

By 1834, Othello—aged 76—was again struggling to survive. In August of that year, another anonymous person wrote to the newspaper after meeting Othello in Dartmouth. The writer told some of Othello’s history to help him find work through recommendations or financial assistance:

In the early part of his life he resided in the United States; where, with honest industry he was in comfortable circumstances, until reduced by a destructive fire, by which he sustained a loss of £3000. After the misfortune he removed to Halifax, and was once more in a fair way of doing well. This, however, was of short duration; for he was again burnt out, losing by this incident the value of £2000. Since that period, he has been plodding through life, under the frowns of fortune, and is now living in a small house at Dartmouth in abject poverty. He is far advanced in years, and his eye-sight has considerably failed. During the last winter he suffered much: his hands and feet were frozen; which, with scarcity of the common necessaries of life, rendered his state truly wretched. He has frequently sought in vain for employment of any kind.

(Acadian Recorder, Aug. 2, 1834)

What kept Othello going? Pride, determination, a strong spirit? Likely all those things and, of course, necessity. There was no social safety net, and aid to the poor often depended on charity. Still, Othello was better off than many Black people living in poverty; his fame had faded, but his name was still recognizable, and that may have been enough to attract some small assistance.

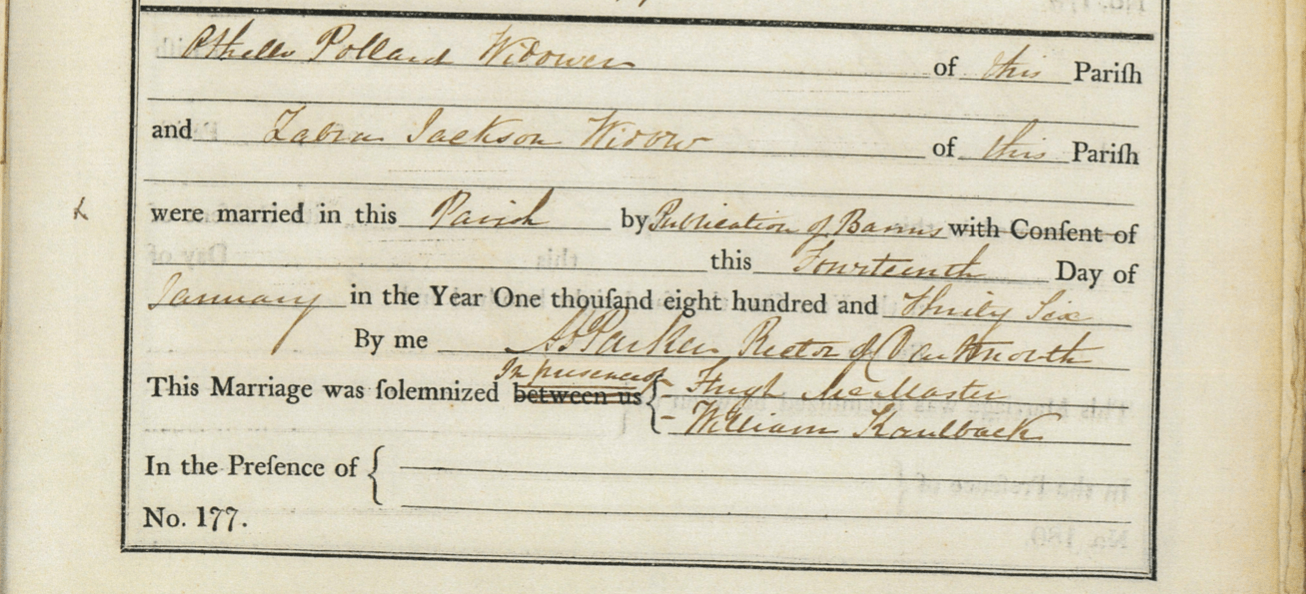

Dartmouth marriage

While in such diminished circumstances, Othello—78—married Tabia Jackson, reportedly 106, in Dartmouth in 1836. Despite the large age gap, both were widowed and from Pennsylvania. This second marriage might have been for love but could have been for convenience. Perhaps he sought relief or comfort or companionship.

Tabia was called “Desdemona” in the marriage announcement in the newspaper and elsewhere—a Shakespearean nickname to match Othello that also carried an undercurrent of mockery. Tabia, also known as “Zebra” and “Old Mrs. Pollard,” was known as a “fortune teller” and lived in downtown Dartmouth in a small cottage on Quarrell (now Queen) Street. Presumably, Othello lived with her until his death in 1844. Tabia survived Othello by two years.

In the 1838 Census Return for Halifax County, opens a new window, Othello was described as a “Cook” living among “Colored People in Dartmouth.” His household included one boy under six years old and two women over 14. Were these members of his household boarders, his wife’s relatives or his own? It is unknown if Othello left any US or Nova Scotia descendants.

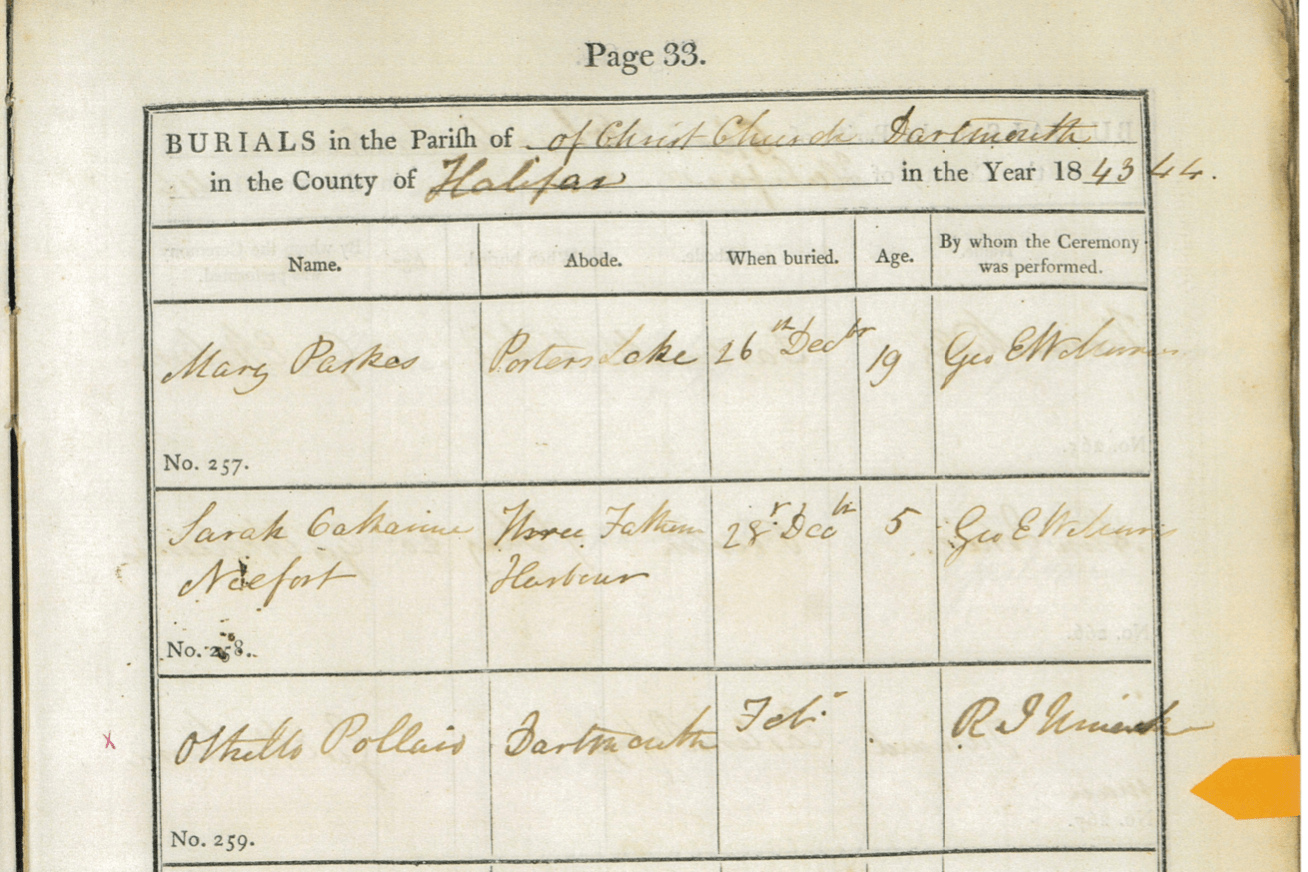

Death and burial

Othello died in Dartmouth in January 1844 during an extremely cold winter and was buried at Christ Church. No plot location was recorded for Othello, so the exact location of his grave in the cemetery is unknown. According to the Church’s Historical Committee, there is an area of unmarked Black graves that was once outside the “official” cemetery grounds; it is most likely that Othello rests there among other unidentified and forgotten members of the Black community.

Othello lived to the old age of 86 with courage and perseverance. He reached great heights in business and culinary arts, but circumstances out of his control reversed his fortunes. Had age and a loss of resources been the main cause of this reversal? Had Halifax been a more challenging city than Boston to make a go of it for an ambitious and entrepreneurial Black man?

He was unable to achieve the financial and professional success in Halifax that he once enjoyed in Boston. Despite the significant obstacles he encountered throughout his life, Othello never stopped trying to overcome them.

Thank you to Janice Silver, Historical Committee Chair, Christ Church, Dartmouth, for information about the burial grounds and to Lorraine Slopek, Diocesan Archivist, Anglican Diocese of NS and PEI, for finding Othello’s marriage and burial record.

Sources

The Acadian Recorder (Nova Scotia Archives):

Vol. 4, no. 25, June 15, 1816

Vol. 9, no. 38, Sept. 22, 1821

Vol. 16, no. 8, Feb. 23, 1828

Vol. 19, no. 45, Nov. 19, 1831

Vol. 19, no. 46, Nov. 26, 1831

Vol. 19, no. 49, Dec. 3, 1831

Vol. 19, no. 51, Dec. 17, 1831

Vol. 19, no. 52, Dec. 24, 1831

Vol. 20, no. 34, Aug. 25, 1832

Vol. 22, no. 31, Aug. 2, 1834

Vol. 24, no. 3, Jan. 16, 1836

The African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, http://www.aecst.org/about.htm, opens a new window

Anglican Diocese of NS and PEI Archives

Boston Gazette, vol. 14, no. 30, June 13, 1803; vol. 14, no. 38, Jul. 11, 1803.

Boston Weekly in American Periodicals, Vol.1 (Oct 1802-Oct 1803), Jan. 22, 1803.

“British Spy in Boston.” Norfolk Gazette and Publick Ledger (Virginia), vol. 1, no. 82, Jan. 23, 1805.

Census Returns, 1838, Dartmouth, Halifax County (Nova Scotia Archives).

Columbian Centinel (Boston), vol. 37, no. 25, May 26, 1802; vol. 37, no. 51, Aug. 25, 1802; vol. 44, no. 18, Nov. 2, 1805.

“Dandy Jack.” Daily Evening Transcript (Boston), vol. 21, no. 6210, Oct. 8, 1850.

Douglass, William. Annuals of the first African church in the United States of America: now styled the African Episcopal church of St. Thomas Philadelphia. King & Baird, 1862, p. 109.

“From John Quincy Adams to Thomas Boylston Adams, 1 April 1805,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-03-02-1399, opens a new window.

Freedman, Paul. Why Food Matters. Yale University Press, 2021, pp. 84-85.

“Halifax, 1810.” Historical Maps of Halifax, Nova Scotia Archives. https://archives.novascotia.ca/maps/archives/?ID=273, opens a new window

Halifax County Deeds (Nova Scotia Land Registry):

Book 40, Page 220 (M. Clark and others to O. Pollard, 1812)

Book 40, Page 221 (O. Pollard to J.B. Angus, 1812)

Book 40, Page 222 (O. Pollard to J. Thom, 1812)

Book 40, Page 223 (J. Thom to O. Pollard, 1812)

Book 44, Page 169 (O. Pollard and Wife to G. Robertson, 1818)

Book 44, Page 176 (O. Pollard to G. Stewart, 1818)

Book 46, Page 188 (C. DeWolfe and others, 1820)

Book 46, Page 191 (G. Robertson to W.B. Almon and others, 1820)

Book 47, Page 214 (J. Clarke and others to O. Pollard, 1822).

Harris, Jessica B. High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America. Bloomsbury, 2011.

Martin, John P. The Story of Dartmouth. Self-published, 1956.

Muckenhoupt, Meg. The Truth About Baked Beans: An Edible History of New England. New York University Press, 2020.

“Old Time Halifax, 1749-1830; Showing the locations of early Inns, Coffee Houses, and other items of historical interest.” Historical Maps of Nova Scotia, Nova Scotia Archives. https://archives.novascotia.ca/maps/archives/?ID=50, opens a new window

Peregrine, “Original Auto-Biography: Memoirs of a Sensitive Man About Town.” New York Mirror, no. 49, June 7, 1834, pp. 390-91.

“Reminiscences,” New-England Galaxy (Boston), vol. 7, no. 341, Apr. 28, 1824.

Sargent, Lucius Manlius. Dealings with the Dead by a Sexton of the Old School. Vol. 1. Dutton and Wentworth, 1856, p. 29.

Shields, David S. The Culinarians: Lives and Careers from the First Age of American Fine Dining. University of Chicago Press, 2017, pp. 29-33.

The Sun (Halifax), vol. 2, no. 10, Jan. 23, 1846.

Volume of Records Relating to the Early History of Boston, Containing Boston Marriages from 1752-1809, City Document no. 101, p. 152.

Whitaker, Jan. “Taste of a decade: restaurants, 1800-1810.” Sept. 2, 2008, https://restaurant-ingthroughhistory.com/2008/09/02/taste-of-a-decade-restaurants-1800-1810/, opens a new window

Wondrich, David. “The Lost African-American Bartenders Who Created the Cocktail: The Mint Julep Kings.” Mar. 07, 2020,

https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-lost-african-american-bartenders-who-created-the-cocktail, opens a new window

About the Guest Blogger

Kate Foster is a Black Nova Scotian whose writing has appeared in Augur Magazine, filling Station, Understorey Magazine, Canthius and Room Magazine. She lives with her family in Dartmouth, NS.

Add a comment to: Othello Pollard: Remembering an Innovative Black Chef and his Life in Halifax