Written by Vicky, staff member, Halifax Central Library, opens a new window

We are in Mi’kma’ki. We live, work and play on ancestral land that belongs to the Mi’kmaq people; the First Peoples of Nova Scotia. As we seek to build a more inclusive Municipality, we must remember that we are all Treaty People. Those of us who are non-Indigenous have an individual responsibility to acknowledge and address the centuries of injustice, suffering, and broken promises that resulted from European settlement.

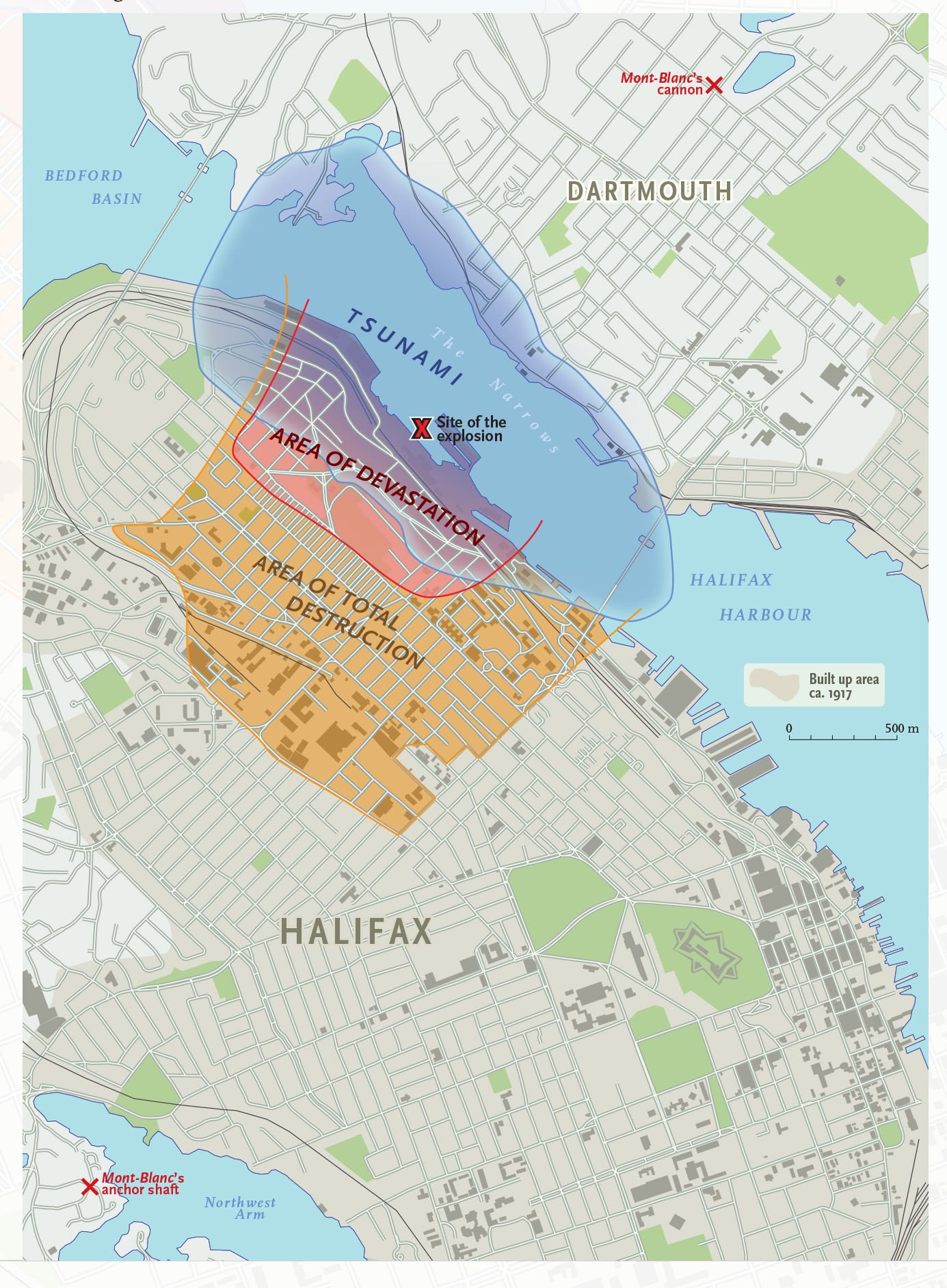

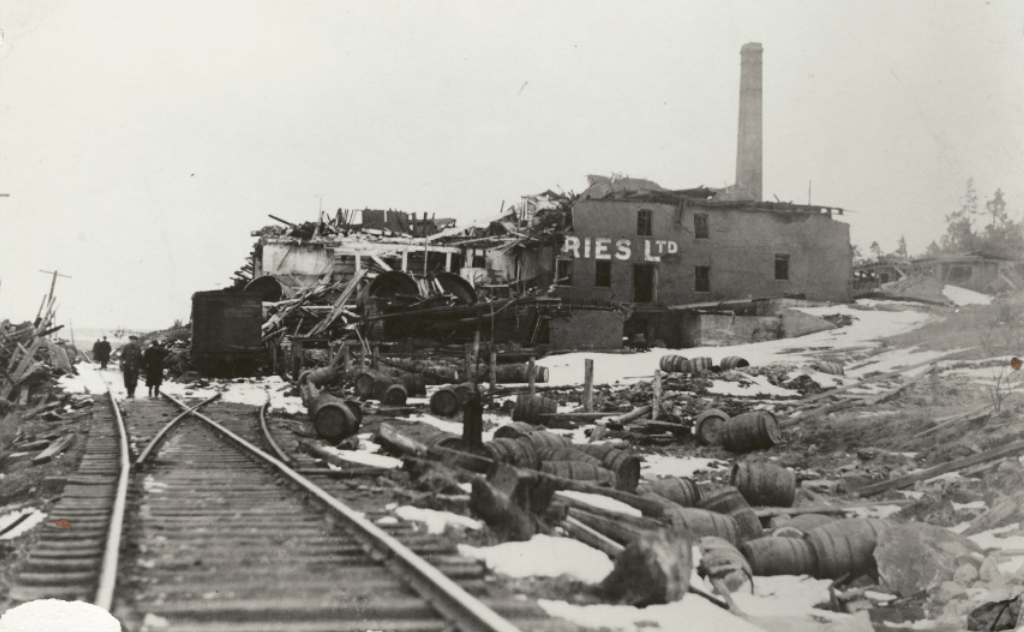

On December 6, 1917, at 8:45am, the SS Imo, a Norwegian steamship, and the SS Mont-Blanc, a French vessel loaded with wartime munitions, collided in Halifax Harbour. Some twenty minutes later, as the people of Halifax and Dartmouth went about their lives—with some watching the wreckage of the now burning Mont-Blanc from the shore—the ship exploded. The blast was so strong that the Mont-Blanc’s anchor shaft was thrown to the far side of the Northwest Arm, and its cannon was found 3km away on Albro Lake Road in Dartmouth. The shockwave reportedly broke windows as far away as Truro, and the force of the explosion was felt 320km away in Sydney, Cape Breton. It was the largest manmade explosion prior to the invention of the atomic bomb, injuring over 9000 citizens, and killing more than 1900 total people.

Though the reconstruction of Halifax and Dartmouth is a well-known story, there is a seldom discussed community that was equally devastated by the 1917 explosion: the Mi’kmaq village of Turtle Grove. Once located in what is Needham Park/Tufts Cove, the community is now on the cusp of a well-deserved resurrection. Let’s take a look at the history of Turtle Grove, and why this lost community is important to our future.

Turtle Grove: The last village standing

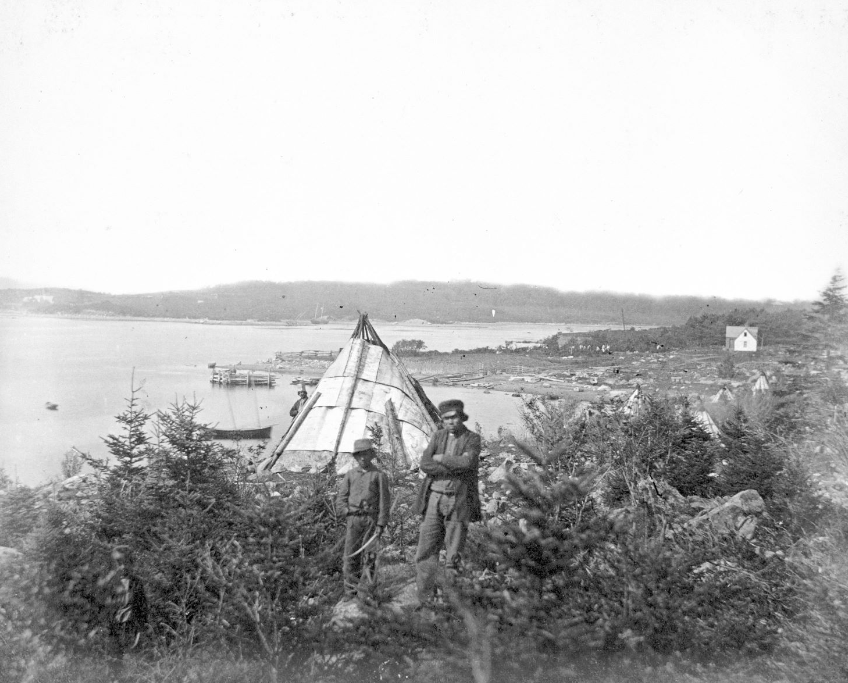

Photo note: This painting is one of many copies of an H. N. Binney 1790 watercolour believed to have been set at Tuft's Cove. More than 50 copies of this scene have been located, each with subtle but important differences from the original. For more information, take a look at "Niniskamijinaqik : Ancestral Images" by Ruth Holmes Whitehead, page 14-15.

The antagonistic and unstable relationship between the British colonialists and the Indigenous Mi’kmaq is well documented and well known. Promises of peace were made and broken; respect, trust, consideration, and courtesy were forgotten; violence was commonplace. In his book, The Confrontation of Micmac and European Civilizations, opens a new window, author Daniel Paul states: “…the British never had any intention, right from the onset of the treaty-making process, to honour their commitments. The British considered treaties to be a means to consolidate their position and lull the Tribes into a false sense of security, and nothing more. The truth of this statement is proven by history” (pg 10).

Halifax Harbour and the land surrounding it were important to the Mi’kmaq, not just as hunting and fishing grounds, but theologically as well. The area between what is now downtown Halifax and Point Pleasant Park was known as Amntu’kati, or Spirit Place. In his article “History of Halifax, a Mi’kmaq perspective” in the Nova Scotia Advocate, author Michael McDonald states the area is central to the Mi’kmaq creation story: “This is … the place where Mi’kmaq believed the Great Spirit Fire sat whose sparks gave birth to the 7 original families of the Mi’kmaq people.” Halifax meant a great deal to the Mi’kmaq, and they wanted to protect it.

Partnered with the French and Acadians, the Mi’kmaq attempted to beat the British back, preventing them from settling in their territory. However, the defeat of the French at Fortress Louisbourg in 1758, along with the expulsion of the Acadians and the deaths of many Mi’kmaq due to the arrival of the foreign disease, took its toll. The battle could not continue. Officially, hostilities ended between the British and the Mi’kmaq with the Burying of the Hatchet Ceremony in 1761, but the end of the war did not mean the end of prejudice.

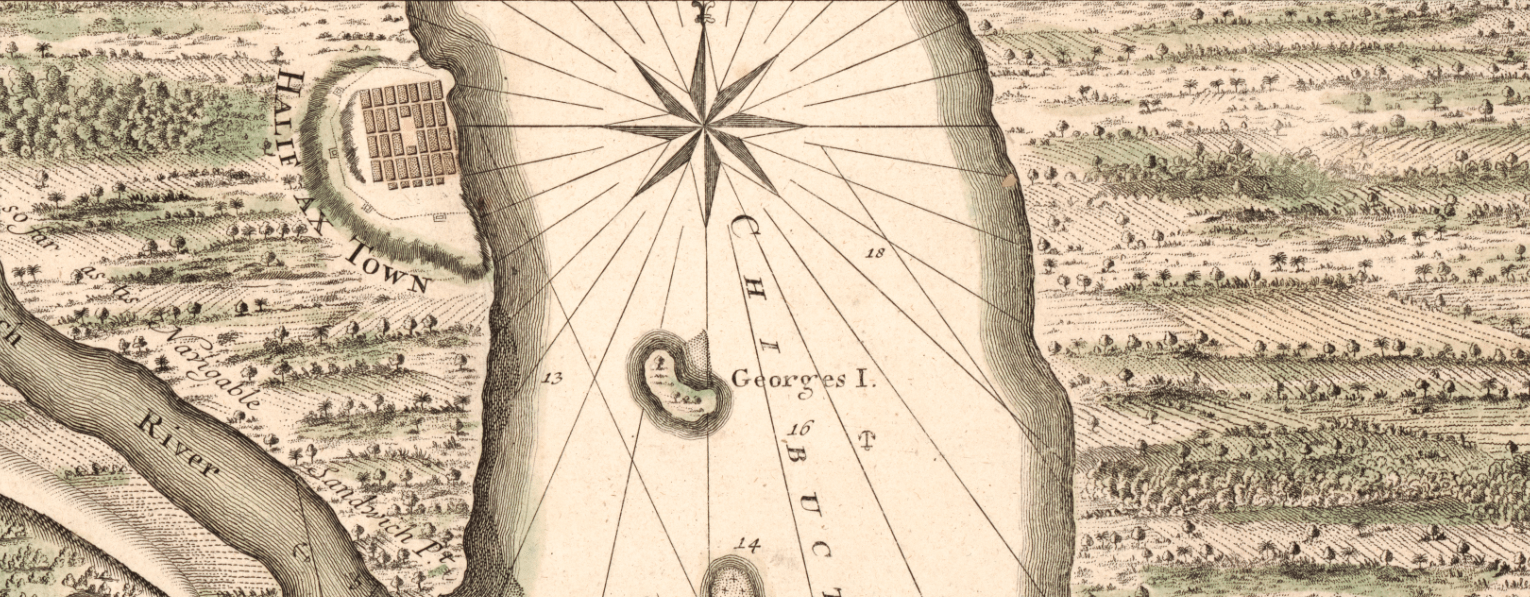

Traditionally, the Mi’kmaq lived a nomadic life as families moved to different areas of the province depending on the time of year and the natural resources available to them. The shore of Halifax Harbour, or Kjipuktuk, was the site of summer encampments for the Mi’kmaq, and Turtle Grove was a warm-weather residence long before the arrival of European explorers. The camp was near the part of the harbour called The Narrows, or Kepe’k, which is aptly named as the distance across the water between Halifax and Dartmouth is at certain points only half a kilometre wide.

As part of their takeover of Nova Scotia, the English Government began a campaign to entice settlers from Britain, Ireland, Germany, France, and other European nations to come to Canada with promises of free land and goods. The property in and around Halifax was divided into lots to be given to incoming citizens. As immigrants arrived, the local Mi’kmaq encampments were displaced, and ultimately disappeared. Turtle Grove, however, remained. Over time, some Mi’kmaq families chose to make Turtle Grove their permanent home, and it eventually became the last of the Mi’kmaq settlements within the city, or near its borders. Several Mi’kmaq families lived there, using traditional wigwams for shelter during the fair-weather months, and switching to simple wooden structures in the winter.

The people of Dartmouth vs The Mi’kmaq of Turtle Grove

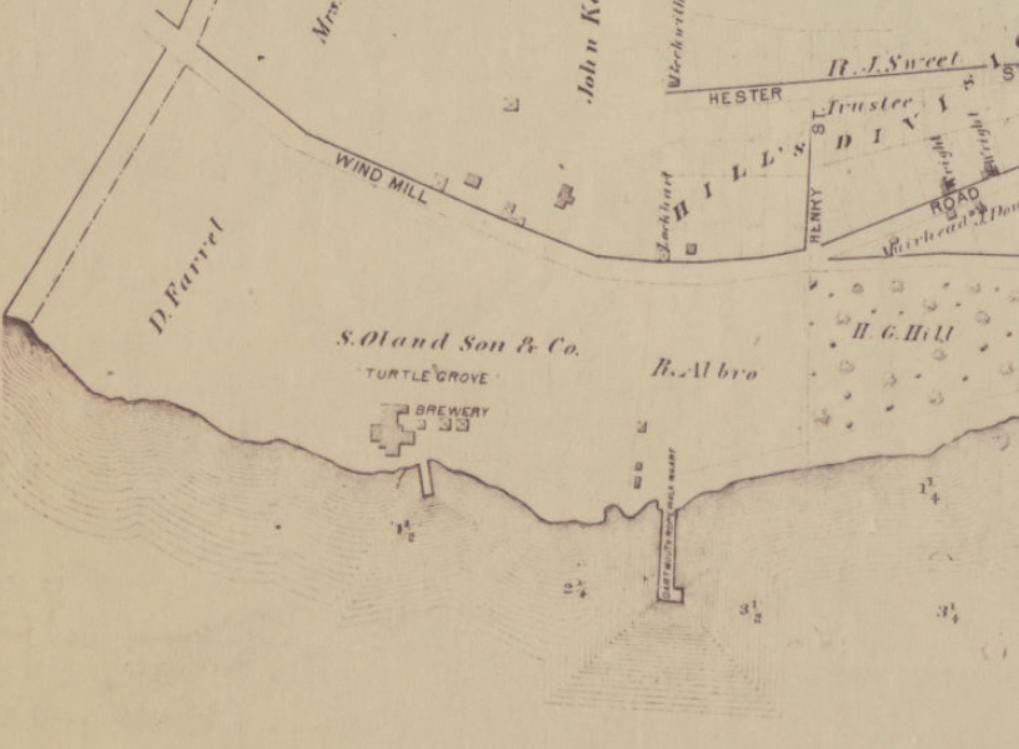

The City of Dartmouth took a little more time to get going compared to its Halifax counterpart. As of 1766, there were a mere 39 people living in the town: 31 adults and 8 children. In his book, In the Wake of the Alderney, opens a new window, Harry Chapman states: “Dartmouth was virtually a ghost town and would remain so for another two decades before the whalers and Loyalists would arrive to breathe new life into the town” (pg 32). In 1790, Gersham Tufts, a carpenter by trade, received a grant of land from the British Crown of approximately 1,000 acres on the Dartmouth side of the harbour. From that point forward the area was known as Tufts Cove, or Nipame’katik (Cranberry Place). The land grant included Turtle Grove. Though the area was now considered private property, the Mi’kmaq continued to live on the land as they always had. In the eyes of the property owners and the government, this made the Mi’kmaq trespassers and Turtle Grove became a point of contention.

The debate over the Mi’kmaq encampment continued for decades, even as the properties were divided and changed ownership. In another of Harry Chapman’s books titled The Halifax Harbour Explosion: Dartmouth’s Day of Sorrow, opens a new window, the author makes note of a specific dispute:

Vincent Farrell, a prominent Dartmouth businessman, wrote to the Department of Indian Affairs in 1905 complaining to the federal government that the native people at Turtle Grove were squatting on his sister’s land and he wanted them relocated… the native community lived with constant harassment and threats of expulsion and relocation from both the Farrell family and the federal government (pg 16).

This letter acted as a catalyst that began several years of negotiation between the Department of Indian Affairs and the Mi’kmaq to find them a new place to live. In 1912, a piece of property referred to as the Old Quarantine Grounds, which was only a short distance away from Turtle Grove, was offered by the government as a possible alternative. The Mi’kmaq accepted the offer, but it was later rescinded when the citizens in Tufts Cove complained. The government also made efforts to try and purchase Turtle Grove from the Farrell family, but could not afford the $20,000 they were asking for it.

In 1916, there was a breakthrough. The Tufts family offered the government a 94.5-acre plot near Albro Lake. Though the Tufts had been opposed to the Mi’kmaq moving to the Old Quarantine Grounds, this new proposal appeared to be a reasonable alternative. The land would be designated as a reserve, which would mean the government would fund medical supplies and housing. They also offered $2,500 to aid with moving expenses for the families. The Mi’kmaq accepted. The transition to the new land was meant to begin immediately, but as December of 1917 approached, the move had not yet started.

The disaster

As the Mont-Blanc burned, many people on both sides of the harbour watched from the shore. It was a surprise to citizens watching from Tufts Cove when lifeboats from the Mont-Blanc landed at the ferry wharf and the men who disembarked began screaming at them to run. One of the people alerted to the danger was William Paul, a young Mi’kmaq boy from Turtle Grove. William ran home to his mother, Mrs. Paul, who was pregnant at the time and home taking care of her infant daughter, Madeline. William tried to convince her the family needed to flee, but she dismissed him, thinking he was just being over-imaginative about the doomed ship. But not long after, the sounds of small explosions filled the air as individual barrels of explosives began to detonate. At 9:04am, the Mont-Blanc blew up:

At Turtle Grove, William Paul’s mother awoke on the ground… A baby was crying. It sounded muffled as if she were swaddled too tightly. Mrs. Paul stood up, her dress hanging off of her in strips. It was dark; smoke obscured the outlines of the buildings and she could not see her house… Mrs. Paul cocked her ear to listen for the crying Madeline, but every few seconds something crashed out of the sky and exploded next to her. It was hard to concentrate. She shuffled over a pile of timber that she only then recognized as her house… She dug… until she exposed part of the stove. It was intact and upright on its curled feet, but the oven door was ajar. Mrs. Paul pulled open the door and looked inside. Baby Madeline was lying on top of a bed of hot coals. The back of her swaddling was scorched and her back burned… but she was screaming vigorously. The cries were a good sign…

— MacDonald, Laura, “Curse of the Narrows, opens a new window,” pg 81-82.

The explosion destroyed almost everything in its path. Buildings collapsed, trees were pulled from the ground, witnesses claim the water in the harbour was boiling from the heat; it was carnage. But it was not only the explosion itself that caused devastation; there was also the tsunami that followed:

A semicircular tsunami rippled outward across the harbour, picking up more water and force until it was twenty feet high. The wall of water picked up bits of metal, swept men off decks, broke mooring lines, and spit ships aside as it sped outward to the Basin and the sea. The worst of it hit Tuft’s Cove, where it crashed over people, trees, and houses.

— MacDonald, Laura, “Curse of the Narrows,” pg 66.

Remarkably, William, Madeline, Mrs. Paul, and her unborn child all survived the disaster, though Madeline would be hospitalized for many months to help heal her burns. Others were not so lucky.

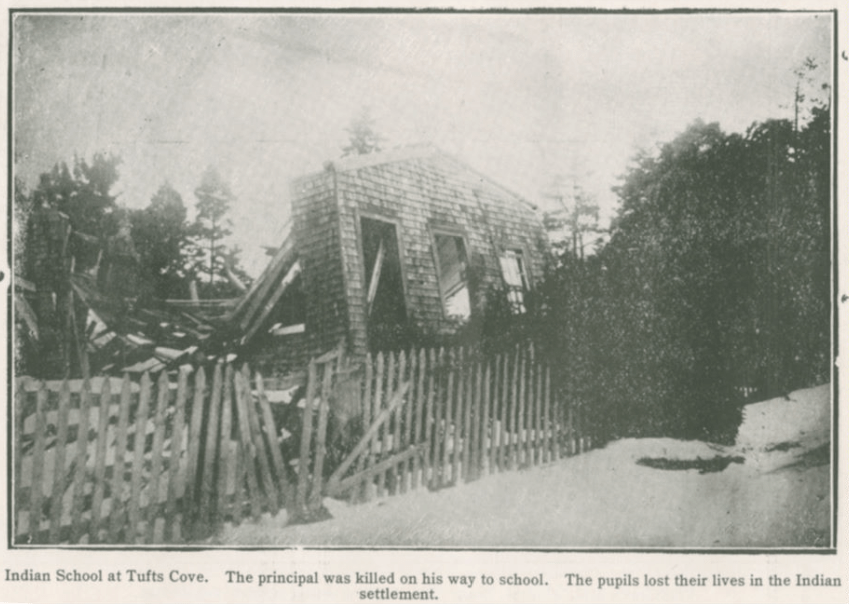

The number of Mi’kmaq killed in the Halifax Explosion is not clear. Though many sources claim nine deaths, others account for the total to be much higher—upwards of 30. Cathy Martin of Millbrook First Nation, a Mi’kmaq community near Truro, Nova Scotia, remembers her Aunt Rachel telling her about that fateful day. Rachel, who lived in Windsor Junction, but attended school at Tufts Cove, would have been about ten years old when the disaster occurred. She, her brother, and her cousin were on their way to school when the Mont-Blanc exploded. When Rachel awoke after the blast, some of her family had found her; she had been placed on top of a door that had come off of its frame and covered in blankets. A woman was singing to her in Gaelic, and trying to feed her chicken soup. A priest performed the last rights, but despite being expected to die, Rachel pulled through. Her brother, Henry, and her cousin Louis, did not survive, nor did Rachel’s younger brother, Frank, who was severely burned and later succumbed to his injuries. Chapman’s book In the Wake of the Alderney , opens a new windowstates that the 1917 annual report for the Department of Indian Affairs sited that no survivor from Turtle Grove was left unharmed.

Turtle Grove was completely obliterated. Though some relief was provided through the Department of Indian Affairs and the Dartmouth Relief Commission, unlike the neighbouring communities, Turtle Grove was not rebuilt. In the Halifax Signal article “The Story of Turtle Grove” by Ava Coulter, historian Jacob Remes states: “…the big thing that happens is the thing that doesn’t happen… The school doesn’t get rebuilt, the settlement is prevented from being rebuilt.” The reservation at Albro Lake never came to be. Coulter notes: “The explosion had ultimately helped the government and settler neighbours raze the community – a goal they tried to achieve for years.” Though a few Mi’kmaq resettled locally, many who survived scattered throughout the province.

Coming home again

Dartmouth in the 1920s saw a great deal of reconstruction following the explosion; the 1930s brought hardship on business and families alike with the start of the Great Depression; the 40s saw a resurgence in manufacturing as demands for supplies skyrocketed during World War Two; the 1950s saw a residential boom, with new houses being constructed. For Turtle Grove/Tufts Cove, this meant a new 33-hectare neighbourhood called Shannon Park, built by the Department of National Defense to house military officers and their families. The Nova Scotia Power Generating Station opened in 1965, and the MacKay Bridge soon followed with its grand opening in 1970. To most people, Turtle Grove and the Indigenous population that lived there was a distant memory or an interesting historical fact. But to the Mi’kmaq, it was still very real. Cathy Martin returns to the shores of Turtle Grove every December 6 to call out the names of her ancestors. In a 2017 Globe and Mail article, Martin stated: “Their spirits are here. The more we say their names, the better they can rest and know that we haven’t forgotten them.” (“Their spirits are here”: The Halifax Explosion’s untold story of Mi’kmaw communities lost, Dec. 2017).

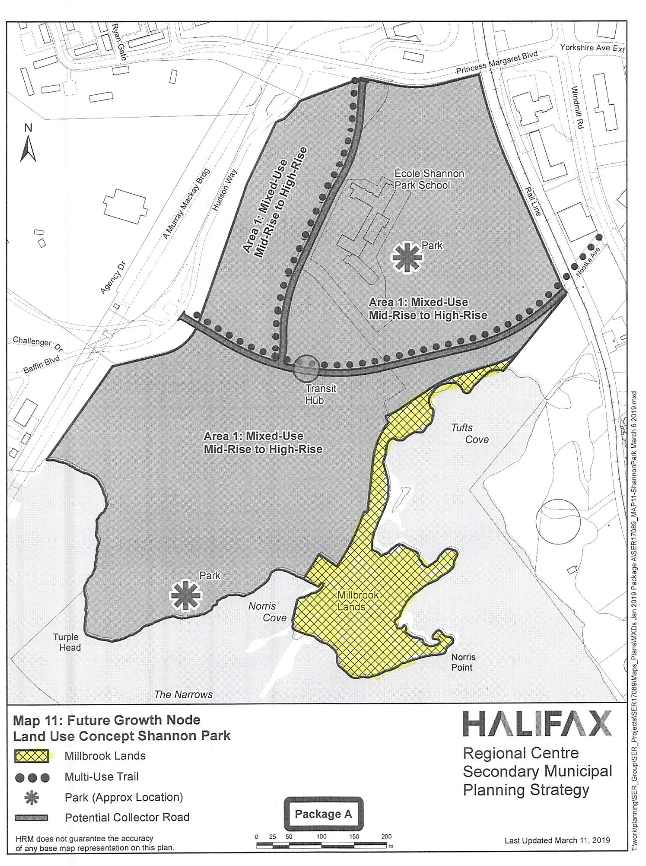

After many years as a home for military personnel, the Department of National Defense made the decision to close Shannon Park. By the early 2000s, the site was abandoned leaving behind more than 400 empty apartments, two schools, a store, churches, an arena, a swimming pool and a community centre. The Department of National Defense was interested in selling the property, but Millbrook First Nation put forth a claim for a portion of the land. Shannon Park could not be sold until the claim was settled. Though offered financial compensation, then Chief of Millbrook First Nation Lawrence Paul stated in a 2004 Chronicle Herald interview: “We’re not into that, taking cash payments… We’ll develop the land and use it for economic development purposes, for the future of the Millbrook First Nation.” (Halifax Chronicle Herald, April 18. 2004, pg 3). Negotiations were lengthy, but ultimately, in 2014, the Department of National Defense divided the land into three pieces.

The majority of the property – approximately 33 hectares – was sold to Canada Lands Company, a part of the federal government that deals in real estate. Canada Lands Company also purchased 1.89 hectares with the intention of negotiating a sale to the Halifax Regional School Board, as the land currently houses Shannon Park Elementary School. The last portion of approximately 3.89 hectares was transferred to Indigenous Services Canada to fulfill the land claim on Turtle Grove. Ownership of the property was transferred to Millbrook First Nation for development. Though there have been many discussions about what was to be built on the Canada Lands Company portion of the property – a stadium, new housing, etc – the vision from Millbrook First Nation’s perspective has been clear: create a reserve and serve the community.

For the development to begin, both Millbrook First Nation and the Halifax Regional Municipality had to agree to work together in order to provide Municipal services such as public transit. In November of 2020, Robert Gloade, current Chief of Millbrook First Nation, wrote to Mayor Mike Savage:

As Chief of Millbrook First Nation, Millbrook is please(d) to advise it is in the final stages with Indigenous Service Canada regarding its Reserve creation for a (small) section of the Shannon Park Lands… As Mayor, your awareness and support of Millbrook’s Shannon Park reserve creation is important to us. Millbrook is extremely pleased with its positive relationship… with HRM and you as Mayor and look forward to getting together with you and your staff to negotiate a Municipal Services Agreement…

In December, Jacque Dubé, the Municipality’s Chief Administration Officer, wrote Chief Gloade a response:

…I support the creation of the reserve and look forward to entering into discussions with the intent to create a Municipal Services Agreement… The next meeting of Regional Council is January 12, 2021. I will ask to add the Millbrook First Nation’s request for the Shannon Park Reserve to the agenda so we may be able to obtain a formal endorsement.

January 2021 brought the vote before the council, and it was agreed that the Municipality would support establishing the reserve, and will proceed with a Municipal services agreement as the project develops.

After more than 100 years, the Mi’kmaq are returning home to Turtle Grove.

Looking forward

“… the Micmac have, in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds, survived genocide, starvation, and unending racist persecution to continue onward with their fight for freedom and justice. Perhaps, with the grace of the Great Spirit, the return of Micmac self-government shall be realized in the near future!”

– Daniel Paul, pg 19.

What happened at Turtle Grove – the theft of the land, the prejudice, the unexpected and terrible destruction – none of that can be undone. But what we can do is embrace a future where Indigenous cultures are supported, respected, and celebrated. The Millbrook First Nation development at Shannon Park is an encouraging step forward toward a more productive, more equitable, and more sustainable relationship.

Changing the past is impossible. But changing the future: we can do that.

Library Resources

Chapman, Harry. “The Halifax Harbour Explosion: Dartmouth’s Day of Sorrow,, opens a new window” Dartmouth Historical Association, 2007. 971.6225 C466da

Chapman, Harry. “In the Wake of the Alderney: Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, 1750-2000,, opens a new window” Dartmouth Historical Association, 2000. 971.6225 C466i

Chapman, Harry. “White Shirts With Blue Collars: Industry in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, 1785-1995,, opens a new window” Dartmouth Historical Association,1997. 338.09716 C466w

Cuthbertson, Ken. “The Halifax Explosion,, opens a new window” Harper Collins, 2017. 971.6225 C9882h

Kitz, Janet and Payzant, Joan. “December 1917: Re-visiting the Halifax Explosion, opens a new window”, Nimbus, 2006. 971.622 K62d

Kitz, Janet E. “Shattered City: The Halifax Explosion and the Road to Recovery, opens a new window”, Nimbus, 2008. 971.622 K62s

MacDonald, Laura M. “The Curse of the Narrows: The Halifax Explosion 1917, opens a new window”, Harper Collins, 2005. 971.6225 M135c

Martin, John Patrick. “The Story of Dartmouth, opens a new window”, Private Printing, 1957. 971.622 M38s

Parker, Mike. “Historic Dartmouth: Reflections of Early Life, opens a new window”, Nimbus Publishing, 1998. 971.6225 P242h

Paul, Denis. “The Confrontation of Micmac and European Civilizations, opens a new window”. 1993. 970.1 P234co 1993.

Vertical Files: “Canada – Armed Forces – Shannon Park.”

Chronicle Herald, “Big Dreams for Shannon Park”, Friday, October 16, 2009, pg unknown.

Chronicle Herald, “Red Tape, Empty Buildings”, Sunday, April 18, 2004, pg 3-4.

Halifax HRM West Community Herald, “Shannon Park Property Still in Limbo”, Week of Monday, March 7, 2011, pg 9.

Online Resources

Nova Scotia Archives , opens a new window

Nova Scotia Archives: Mi'kmaq, opens a new window

Archives Nova Scotia: Historical Maps of Nova Scotia, opens a new window

CTV News: Dartmouth's Shannon Park site to be demolished starting this fall , opens a new window

The Canadian Encylopedia: Peace and Friendship Treaties, opens a new window

The Canadian Geographic: Disaster Reshaped City, opens a new window

CBC News: Shannon Park in Dartmouth Split 3 Ways, opens a new window

CBC News: Turtle Cove Rebirth, opens a new window

Canada Lands Company , opens a new window

CTV News: Indigenous community erased by Halifax Explosion looks to return, opens a new window

City News: Why we'll Never Know the Exact Number of Halifax Explosion Victims, opens a new window

History of the Mckay Bridge, opens a new window

Mi'kmaq Ecological Knowledge Study

History of Halifax, a Mi’kmaw perspective, opens a new window

Mi'kmaw Place Names, opens a new window

The Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, opens a new window

Add a comment to: Turtle Grove and the Halifax Explosion: A Brief and Not at All Definitive History