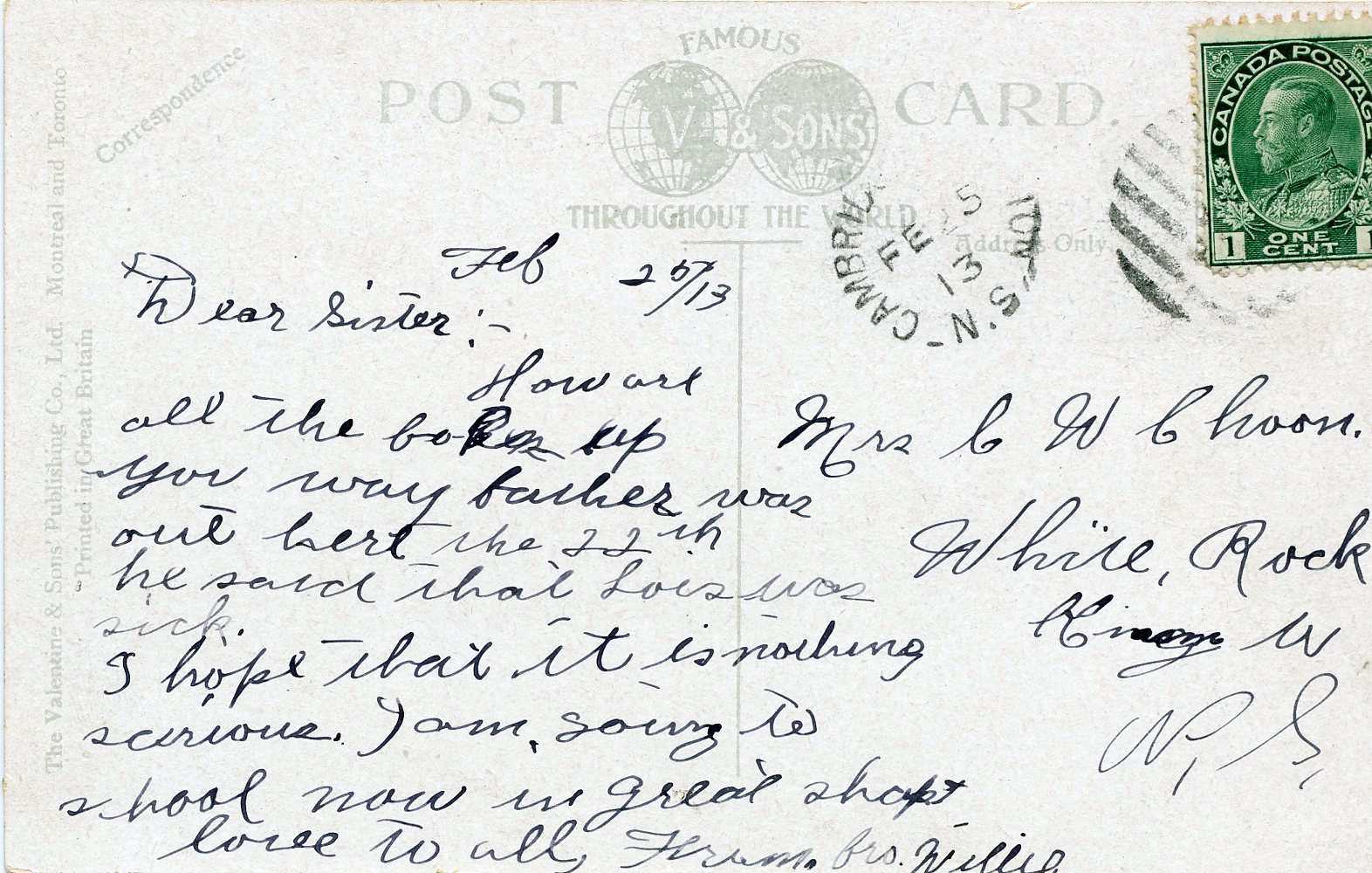

Step back into history using Halifax Public Libraries’ collection of vintage postcards. This collection of 500 postcards gives a glimpse into the past of Halifax and surrounding areas.

Halifax Public Libraries staff members have delved into our Local History collections to learn more about the scenes depicted in selected postcards. Take a trip down memory lane with these journeys into familiar and forgotten Nova Scotian scenes. We look forward to sharing more postcards here with you and on our social media channels, so check back again soon for updates!

Learn more about vintage postcards and our, opens a new window collection., opens a new window

Find the write-up you're looking for faster:

- Acadian Lines

- Allison's Field

- Barrington Street

- Bircham House/Birchdale Hotel

- Citadel Inn

- City Hall

- Cow Bay Beach

- The Carleton Hotel

- Citadel Hill (Interior)

- Dalhousie College

- Dartmouth Ferry

- Dartmouth Shopping Centre

- Geogre's Island

- Golden Gates (Point Pleasant Park Entrance)

- Greenbank

- Green Market

- Halifax Armoury

- Halifax Common

- Halifax Ladies’ College

- Halifax Memorial Library

- Halifax Public Gardens Bandstand

- Halifax School for the Blind

- Halifax Shopping Centre

- Halifax Trolley

- Hubbards

- Jolly Tar

- Jollimore Settlement

- Jubilee Fountain

- Martello Tower

- Old Town Clock

- Picturesque Corner

- Prince's Lodge

- Steel's Pond

- Superintendent's Lodge (Point Pleasant Park)

- Victoria General Hospital

- Womens Council House

Halifax Memorial Library

Written by Amy LeMoine

The history of the Spring Garden Road Memorial Library tells the story of public library service in Halifax. Before its opening date on November 12, 1951, library services in Halifax were lacking. The Citizen’s Free Library had begun sharing books since 1864 and, in 1890, was located inside City Hall. Over the years, Haligonians clamoured for a public library that was more spacious and open to everyone.

After World War II, it was determined that a new library building would be built that would also form a war memorial. The three-storey limestone building was designed by renowned local architect Leslie R. Fairn and was built on top of Grafton Park. The war memorial artifacts added over the years included the Books of Remembrance, a Silver Cross, and flags.

The library boasted 20,000 books when it first opened and housed a children’s library, reading room, and cataloguing department. The first librarian was Mary Cameron. Library membership was free but cost 10 cents for a registration card. Late fees were two cents per day.

By 1955 the space was already deemed inadequate, with more books than shelf space. However, it wasn’t until 1974 that an addition to the building was built, adding 13,000 square feet to the library. This new section gave the library an elevator, new nonfiction stacks, and a new program room.

Once again, the library was full again just a decade later, and the demand for more space grew. Over the next 20 years, debates ranged on how to increase the space—from the addition of a new annex to a completely new building. It was eventually decided in 2008 to construct a new Central Library, and on August 30, 2014, the library closed to prepare to open the new library.

For over 60 years, the Spring Garden Road Memorial Public Library provided books, reference services, youth activities, programs for all ages, and a welcome refuge for all in the heart of downtown. As of 2023, the future of this site and Grafton Park, on which it sits, remains uncertain.

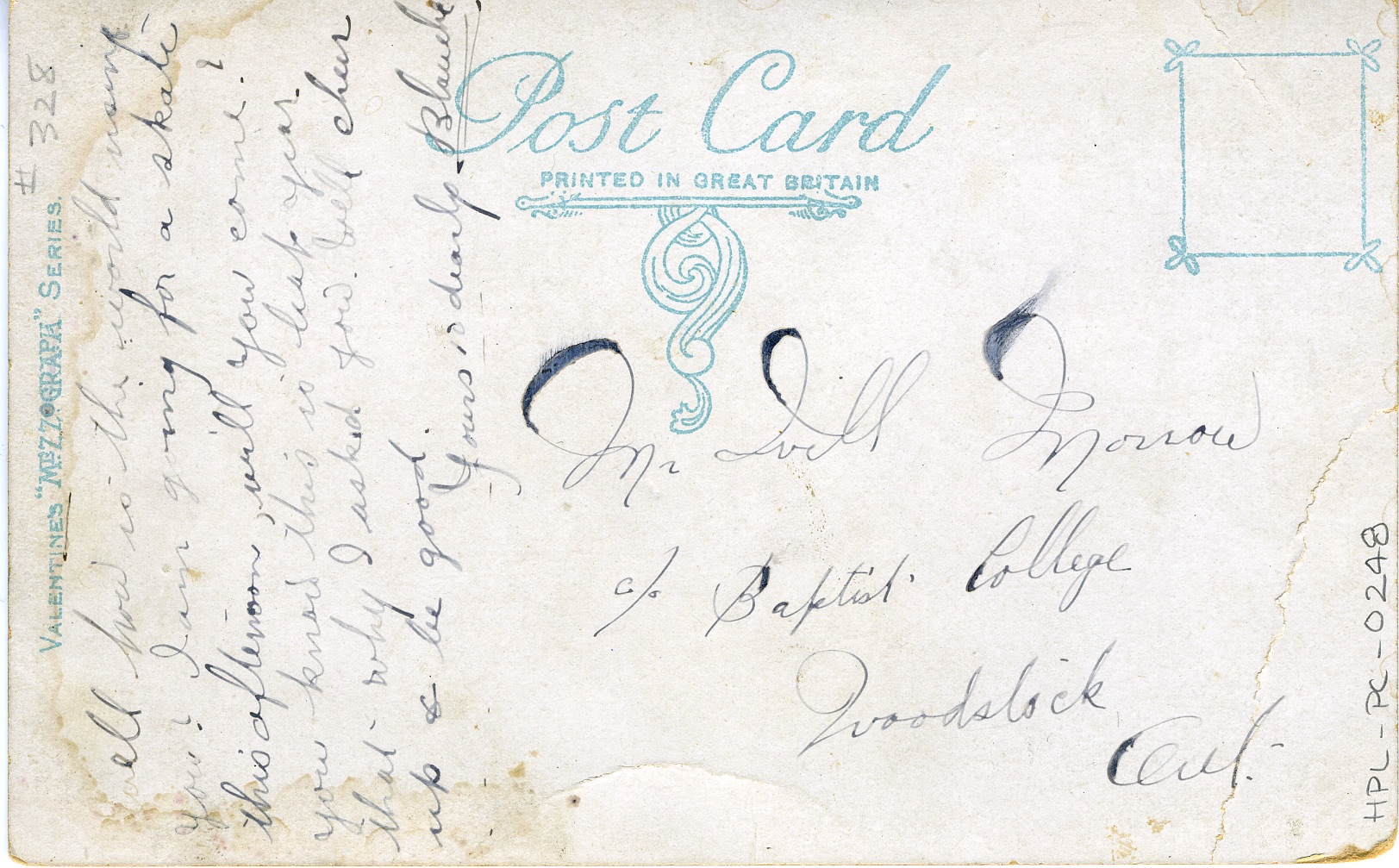

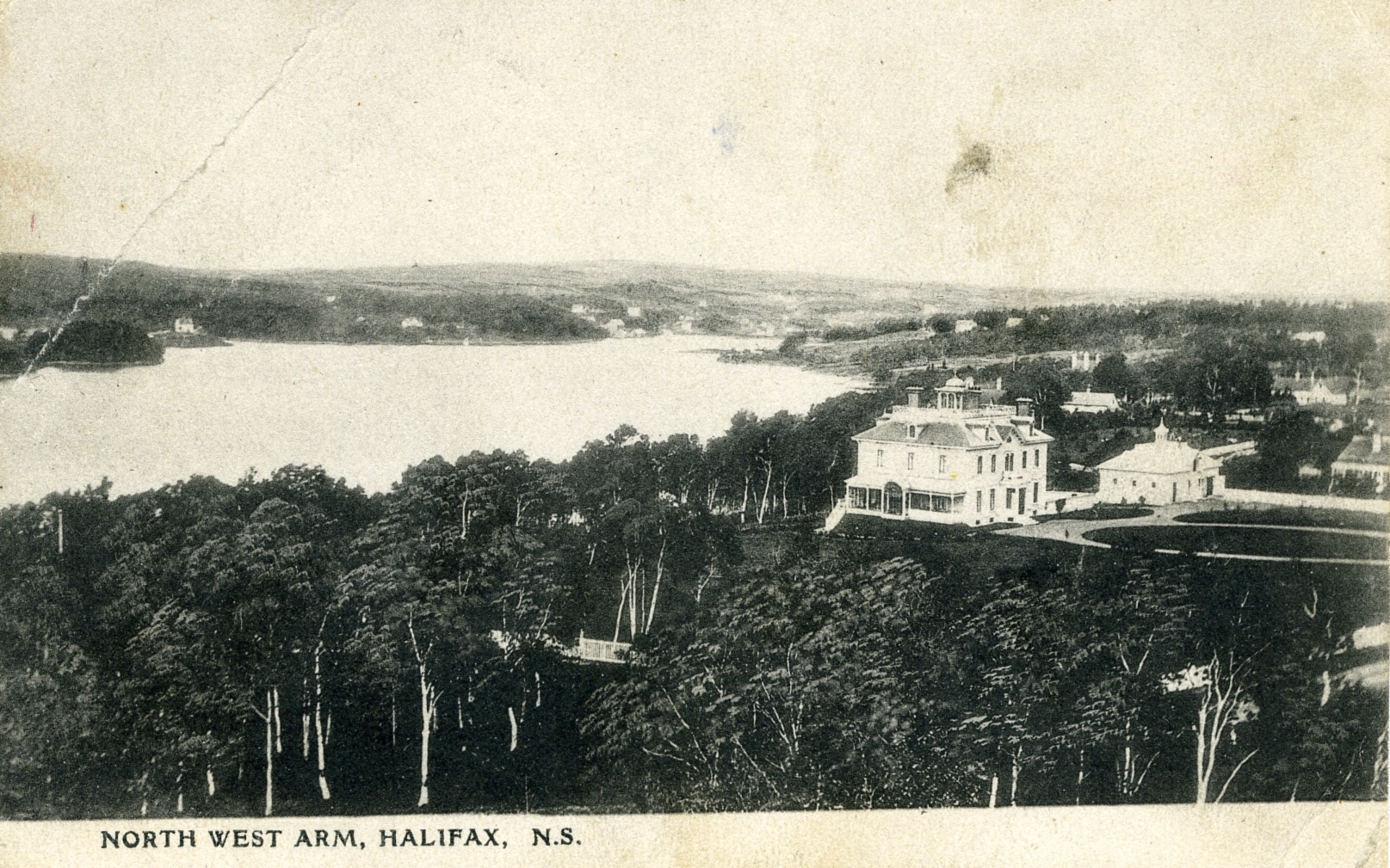

Prince's Lodge

Written by Jamie

Anyone who drives along the Bedford Highway has probably seen this beautiful building on their journey. Did you know that it has been there for over 200 years? It is known as the Music Room, aka the Round House, or the rotunda. This is the last of a once great and sprawling estate that covered a large area in the Rockingham/Birch Cove community that became known as Prince’s Lodge.

Prince’s Lodge was originally built by Sir John Wentworth and included a villa, library, gardens, servants’ quarters, stables, and barns, all of which are long gone. Eventually, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, started staying here with his mistress, Madame de Saint-Laurent, while stationed as garrison commander starting in 1794. Over the next several years, he completely transformed the Lodge, which included the building of the Music Room. Also notable, he played a major role in the building of the Clock Tower at Citadel Hill and St. George’s Round Church.

The Music Room was built right on the edge of the basin so it could be seen from the lodge. Interestingly, no musical performances happened inside the building—they were performed outside on the lawn, where guests could enjoy the scenery. Here, Prince Edward’s regimental band played for him and invited guests. His post in Halifax only lasted a few years, and eventually, Prince’s Lodge was abandoned altogether. By the late 1800s, it was mostly in ruins. Many years later, it became a popular destination because of its backstory and unique layout.

The Music Room has remained a curiosity and attraction all through the 20th Century, and fortunately, stood the test of time with a variety of owners. The trees have grown up around it, but it currently looks much like it did in 1796, complete with all of its pillars, dome roof, and golden ball on top. The government purchased it in 1959 and has been responsible for it ever since.

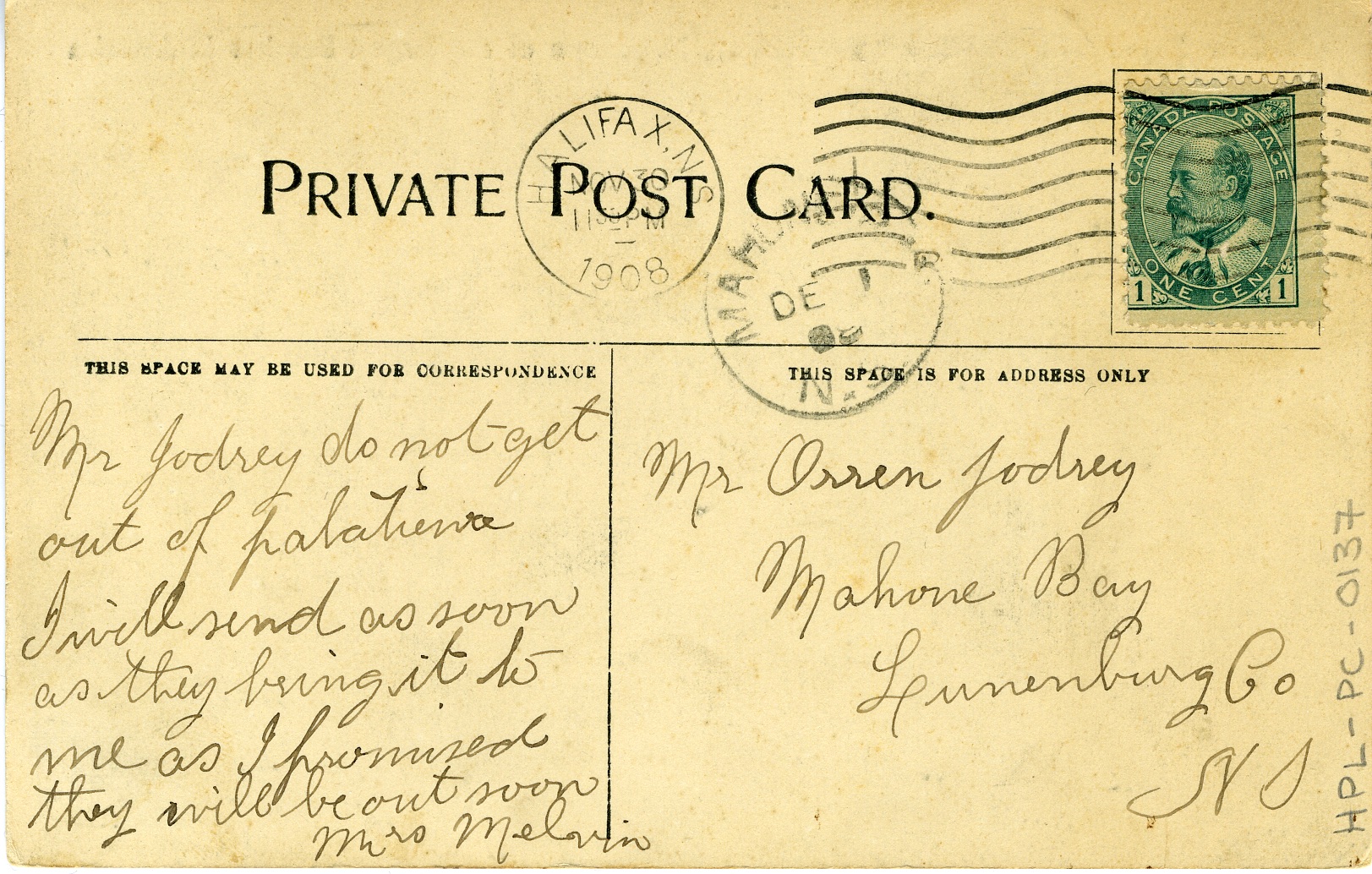

The Old Town Clock

Written by Dandan

The Old Town Clock, located on the east slope of Citadel Hill, began keeping time for the garrison on October 20, 1803. Initially ordered by Edward, Duke of Kent, in 1800 as a timepiece to regulate the garrison, it has served the residents of Halifax for almost two centuries and has become a universally recognized symbol of Halifax.

In the early years, the clock building was used as a guardroom. James Deckmann was appointed the first "keeper of the government clocks." At other times, the building served various roles as an armoury and as a temporary hospital.

In the 1960s, Dennis Gill lived part of his youth with his family in the clock. His father worked for the parks service as the clock caretaker, and he and his family lived inside the clock. The base is a small bungalow with a cellar below and a tower above. Dennis remembered that when they first moved there, the clock was heated with coal. On many occasions, his dad had to wake up in the night and shut everything down because the whole clock would be filled with smoke owing to the very unreliable furnace. He reminisced about his childhood in the clock and the wonderful feeling of security when they lived there.

Today, The Old Town Clock continues to tick away the minutes and hours, although the Georgian Building, which served roles over the years, has been altered a couple of times and majorly restored in 1960. It is maintained and operated by Parks Canada, whose staff wind the clock twice a week to minimize stress on the mechanism.

Picturesque Corner, Herring Cove, N.S.

Written by Joanna Veale

A lovely little house sitting to the side of a lovely little bridge. Where is this "picturesque corner?"

Both the house and bridge were located in Herring Cove at the head of the cove, on the road now named Powers Drive. A building has existed in about the very same spot, at least as far back as 1845. A map from 1864 shows the property was owned by M. Power, and it was later owned by members of the Power family up until the mid-twentieth century. According to photographs, the house appears to have stood at least until 1949, but no longer exists today. The wood and stone bridge that crossed the brook draining Powers Pond into Herring Cove has been replaced by a plainer concrete structure.

The property backs onto the old St. Paul's Catholic Cemetery, now largely abandoned. A stone in the cemetery marks the burial of Michael Power, possibly the same M. Power of 1864. The 1891 Census lists Michael as a fisherman. He and his wife, Elizabeth, had eight children at home, four of whom were sons in their twenties. Like their father, all were listed as fishermen. As of the 1901 Census (five years before the postcard photograph was taken), Elizabeth was widowed, and all her children remained at home. All six of her sons had become fishermen.

The fisheries had been a mainstay for the community of Herring Cove since its beginnings. Only in more recent times has that shifted; the last working fisherman retired in 2018.

Herring Cove was originally known by the Mikmaw as "Moolipchugechk," meaning narrow and deep chasm or valley. It was later known as Dunk Cove after George Montagu-Dunk, the 2nd Earl of Halifax (and namesake of Halifax), and finally as Herring Cove, either because of the bounty of herring in the waters or for the surname of past residents.

Bircham House/Birchdale Hotel

Written by Dandan Xu

The Bircham House, later known as the Birchdale Hotel, was located at the bottom of Coburg Road and overlooked the stunning Northwest Arm. Robert Morrow Jr. inherited the property from his father and, with his wife Helen, built the house on the land. Constructed in the mid-19th century, the lavishly designed house had some unique features, including a saltwater aquarium in the basement where Morrow, a man with a keen interest in natural history, kept live fish for his studies.

In 1906, F.W. Bowes purchased the Bircham property, along with its neighbour, Bloomingdale, with the intention of creating a tourist hotel by combining the two. Bowes, who was a former director of Carleton House on Argyle Street and a former news editor of the Halifax Chronicle, named his new hotel Birchdale, taking elements from both Bircham and Bloomingdale. He transformed the Bircham house into a hotel, adding two new wings to the building. The Birchdale Hotel had many amenities, including a ballroom, a large library, and even its own newspaper, the Birchdale Bugle. Its prime waterfront location allowed guests to enjoy boating on the Northwest Arm and was a popular destination for tourists in the summer and for locals year-round.

After its time as a hotel, the Birchdale building was sold to Dalhousie University, where it was briefly used as a residence for men. King's College then took over the Birchdale when the school relocated from Windsor to Halifax in 1923. Over the years, the building served many purposes, including a grand house, hotel, and university residence. However, by the early 1930s, it was demolished, bringing its story to a close.

References:

Ballard, J. M. A. (2018). Historic house names of Nova Scotia. Nimbus Publishing.

Dawson, T. (2011, March). The many chapels of King’s College” The Griffin, 36(1), 3-5.

Places: Halifax, Halifax Co.: Houses: Birchdale: formerly Robert Morrow’s “Bircham” lately residence of King’s College, Coburg Road. (1931). [Photograph and caption]. Nova Scotia Archives Photographic Collection. https://archives.novascotia.ca/photocollection/archives/?ID=6696

Regan, J. W. (1978). Sketches and traditions of the Northwest Arm: Illustrated and with panoramic folder of the Arm (first printing 1908). Hounslow Press.

Student government history: No. 26. (1974, September 26). The Dalhousie Gazette, 107(3), 2. https://findingaids.library.dal.ca/the-dalhousie-gazette-volume-107-issue-3

Watts, H., & Raymond, M. (2003). Halifax’s Northwest Arm. Formac Publishing Company.

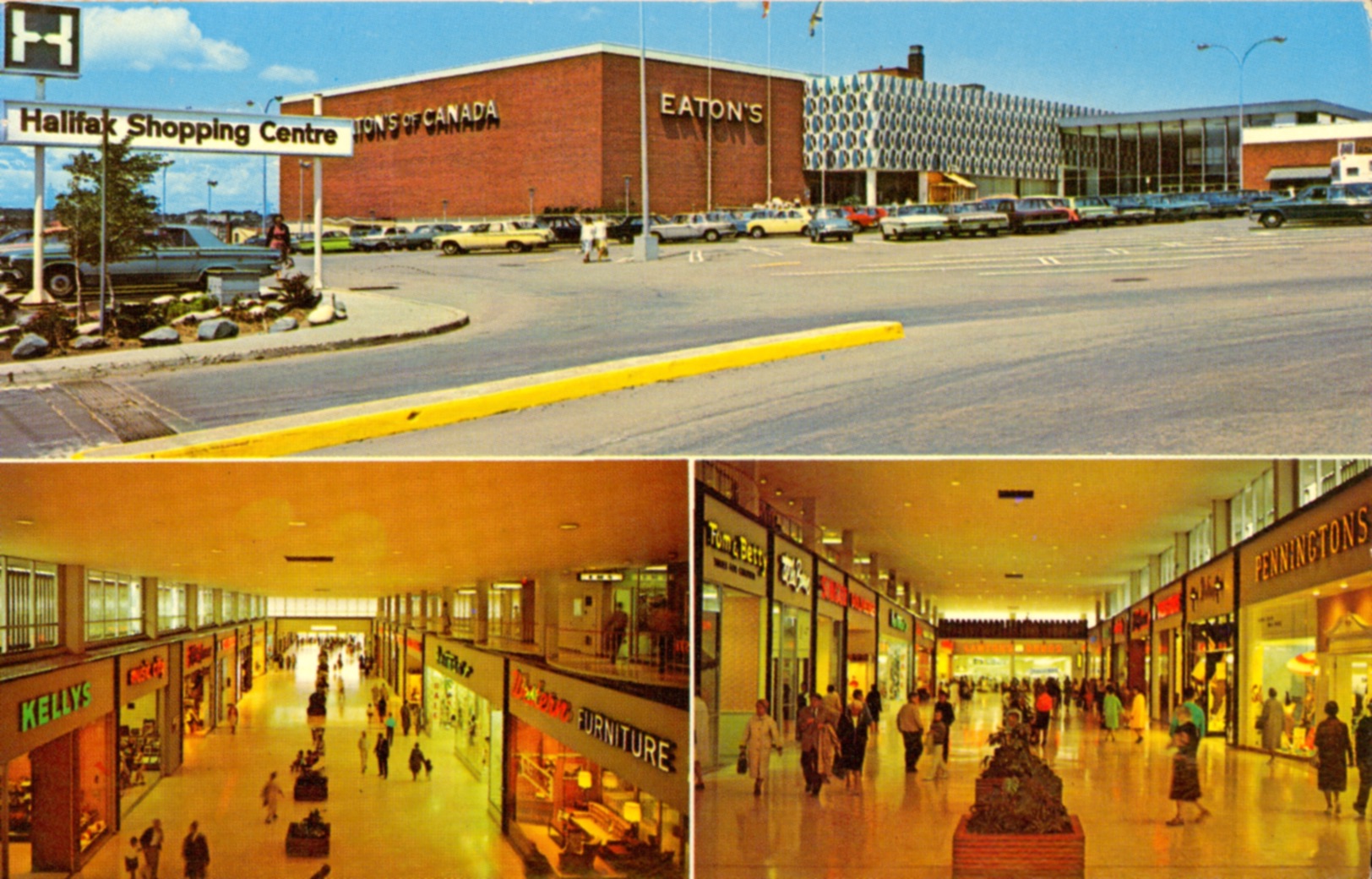

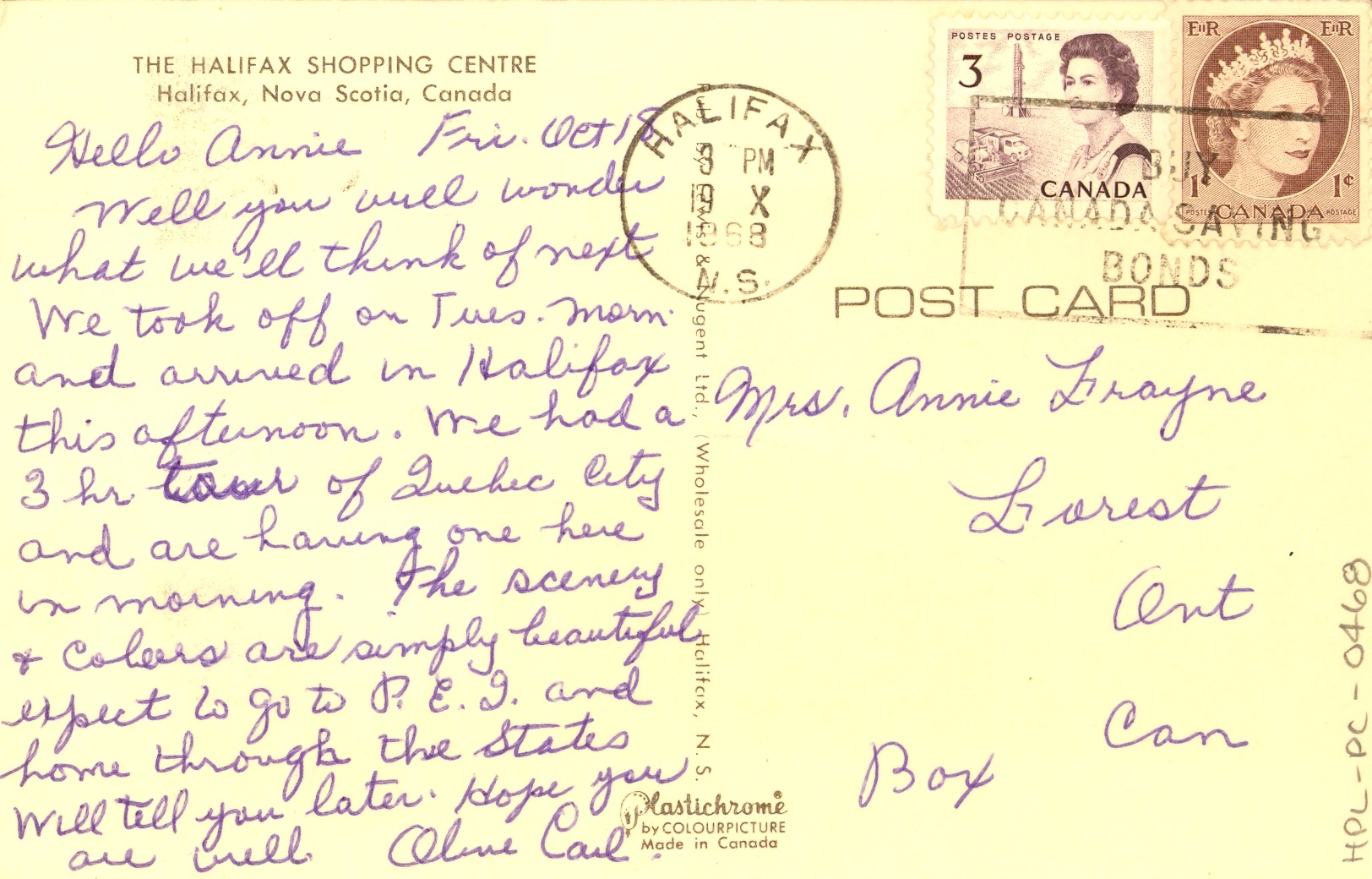

Halifax Shopping Centre

Written by Jamie Drew

The Halifax Shopping Centre is one of the most important shopping destinations that Nova Scotia has to offer. Throughout the years, it has weathered many storms--financial woes, community opposition around multiple expansions, and changing consumer habits. Yet to this day, it has managed to remain relevant and continues to draw many customers. It is both retro and forward-thinking, creating a shopping “experience”, unlike the offerings of big box stores, outlet stores, or online shopping.

When the Shopping Centre first opened its doors in 1962, the world was a different place, and the “shopping mall” was still a relatively new concept. Malls have been around since the 50s, but nothing like this existed on the East Coast. Since its very conception, it was advertised as the “Market Place of the Maritimes.” Modern shoppers found the space appealing with its bright, accessible, fully enclosed climate-controlled environment, where one could do all of their shopping. It cost $9 million dollars to build and housed 50 shops and “ample parking for thousands of cars daily.” At the time, there was nothing quite like it. The mall reigned supreme for 10 years before the Mic Mac Mall in Dartmouth became its biggest rival. In its humble beginnings, the Centre had many big-name stores, including Eatons, Sobeys, Lawtons, and Birks jewellers to name a few.

As this postcard from 1968 shows, shopping here was meant to be an alluring experience for all the senses where one could get away from their normal routine. It was also promoted as an events center with a stage for charitable, social, athletic, cultural, and promotional events beyond the regular shopping hours. As the years passed, there were beauty and baby pageants, trade fairs, celebrity appearances, visits with Santa, craft markets, and antique shows. After a number of recent renovations and expansions, it has once again found its place in the modern world with a focus on more high-end retailers and a completely revamped food court.

Halifax Ladies’ College

Written by Marisa Moreira

This imposing mansion once stood at the corner of Pleasant (now Barrington), Harvey, and Morris Streets and contributed significantly to the broader education of young women in Nova Scotia.

Originally built for Richard John Uniacke Jr.’s wife in 1821, the house was later inhabited by the Duffus family. In 1887, the property was purchased by the recently-created Halifax Ladies’ College in association with the Presbyterian Church of Canada. Immediately after it was established, Halifax Ladies’ College became affiliated with the Halifax Conservatory of Music, Victoria School of Art and Design, and later with Dalhousie University.

The college focused on teaching social skills and cultural norms for young women who were not pursuing a career, and also as a preparatory school for those that were looking for a profession. This elite school included classrooms, a science laboratory, an art studio, a gymnasium, and residential accommodations for about 100 students. Languages, math, and sciences were part of the general education. Sports were well-loved, and music, art or domestic science was the curriculum of choice for girls attending the school.

A notable alumni of Halifax Ladies’ College was Lucy Maud Montgomery. While attending classes at Dalhousie University in 1895-96, Montgomery boarded at the Ladies’ College residence; she enjoyed the proximity to Point Pleasant Park, where she loved to stroll.

In 1917, the school building was severely damaged by the Halifax Explosion but was quickly repaired to be used as an improvised treatment centre. Students and teachers played an important role in relief work.

Another outstanding event for the College was when the school received the visit of Edward VIII, then Prince of Wales. An autographed picture of the prince was published in the Halifax Ladies’ College Yearbook, the “Olla Podrida,” in 1921.

With student numbers declining during the Great Depression, the College started entering in debt. In 1939, the building and property on Barrington Street were expropriated, and it became a hostel for YMCA servicemen. After briefly relocating to Young Avenue, the college moved to Oxford Street. In 1979, the Halifax Ladies’ College became a coeducational day school, and the following year the name of the institution was officially changed to Armbrae Academy.

The original Halifax Ladies’ College building was demolished in 1963 and replaced by the Thompson Building.

References

-MacLeod, S. (1973). A History of the Halifax Ladies’ College, Established 1887.

-McGuigan, P. T. (2007). Historic South End Halifax.

-General Information - About Armbrae. (n.d.). https://armbrae.ns.ca/about.html

Halifax Public Gardens Bandstand

To celebrate Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee and her 50 years on the throne, the iconic bandstand was added to the Halifax Public Gardens in 1887. A grand concert and fireworks display was held in the same year to mark its opening. Funded by City Council and designed by architect Henry Frederick Busch, this fanciful architectural piece vies for attention with its intricate detailing and bold use of colour. The gingerbread decoration on the rails, painted in red, yellow, blue, white and green, cheerfully echoes the exuberant colours and exemplifies Victorian design. The stairway and surrounding balustrade, as well as the columns supporting the roof, are also richly ornamented. The bandstand is surrounded by thirty-two beds of flowering annuals, configured in circles, squares, rectangles, and triangles. The flowerbeds were laid out as early as 1876.

The bandstand remained unaltered until the 1960s when its original copper-clad, wooden roof was replaced with fibreglass. Sadly, some of the finer decorative details of the former roof were removed at this time. Luckily, Busch's design remains little changed, and the bandstand continues to be a Halifax icon. The structure has suffered deterioration over time. Hopefully, a third phase of the Gardens' restoration will restore this Victorian treasure to its former glory.

Being both ornamental and practical, the bandstand is the heart of the Gardens. It has become a favourite informal meeting place where visitors can take their ease on the benches or enjoy leisurely musical strolls in the park when the band is playing, and dusk begins to fall in the Gardens during the warm summer evenings.

Greenbank

Written by Amy LeMoine

Greenbank was a small, tight-knit community that was located in the South End of Halifax in the early 20th century. The neighbourhood was next to Point Pleasant Park, at the south end of Pleasant Street (now Barrington Street) and alongside the Harbour. This small section of town comprised a few dirt roads and between 30-40 homes.

Greenbank was originally built in 1915 by the Intercolonial Railway as a “shantytown” to house workers who were building the railway and port. A few years later, some refugees from the Halifax Explosion settled there. Most of the homes were described as shacks as they were constructed of wood and had tar and gravel roofs. Some Haligonians even referred to the community as “Tar Paper Alley.” The neighbourhood had no running water, electricity, or sewer system, and residents had to walk along the train tracks and dirt roads to reach the rest of Halifax.

Despite the poverty in this area, the community was like family to each other, and they enjoyed a happy life. A small store served as the community focal point, as there was no school or church. Residents enjoyed fishing in the Harbour, swimming at Black Rock Beach in the summer, and skating on Steele’s Pond in the winter. The expansive Point Pleasant Park was their backyard. Many residents worked for the railway or at the nearby docks.

Greenbank lasted until 1956, when the land was sold to develop the container pier, and the homes were torn down. The names of the streets that were lost were Clarence, Owen, Plover, and View Streets.

Today the area is covered by the Shipping container port and the apartment building Ogilive on the Park. Despite the years that have passed, the Greenbankers still gather for occasional reunions that are sponsored by resident Bill Mont.

References

-McGuigan, P. T. (2007). Historic South End Halifax. Nimbus.

-Napier, J. (8 September, 1986). The Greenbankers: They meet again to swap memories. Mail Star.

-Edwards, T. (September 1997). Halifax past: Greenbank. Southender Magazine.

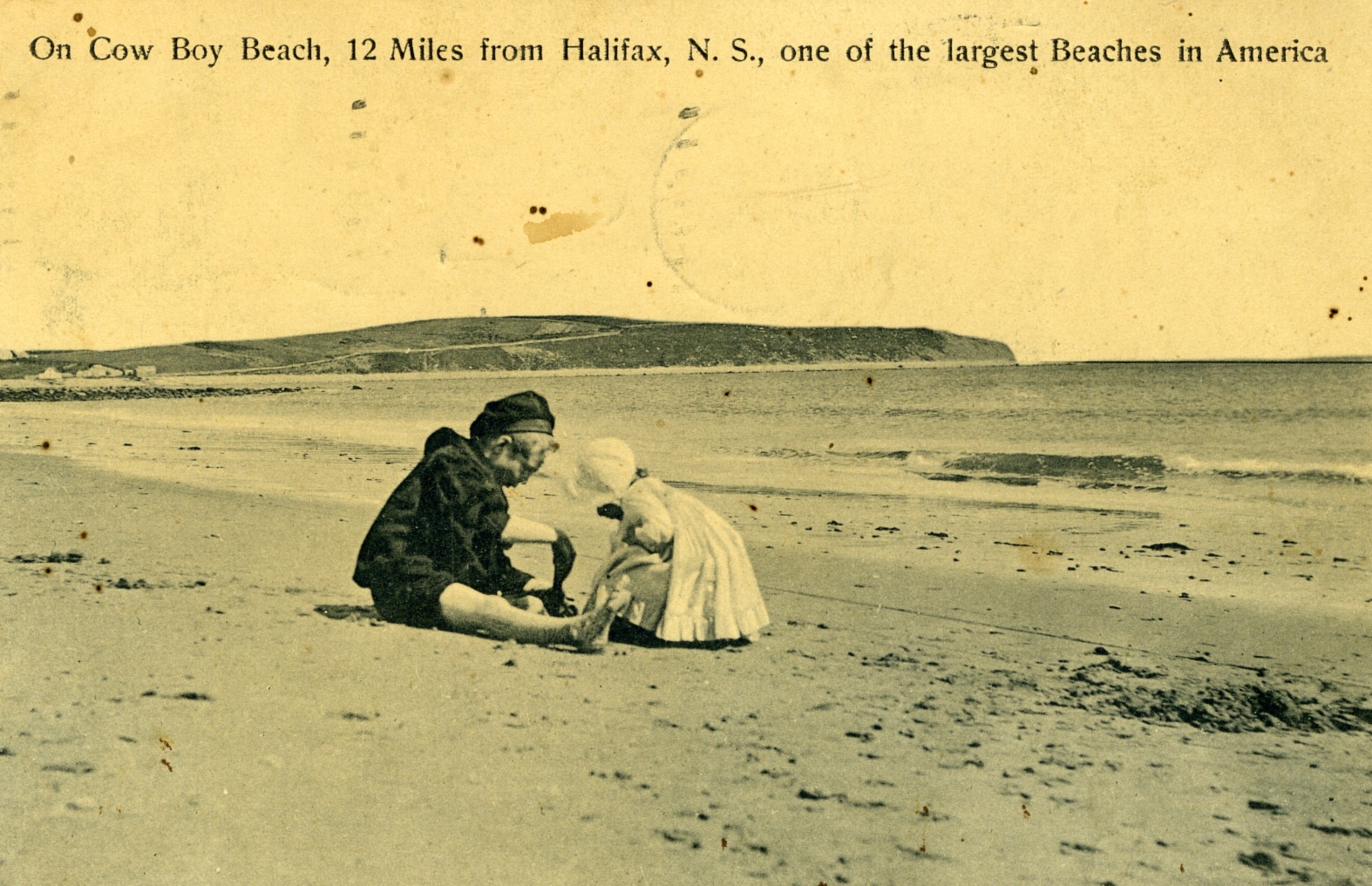

Cow Bay Beach

The image in this postcard is familiar. Given its name, “Cow Bay Beach,” one can presume this beach in Cow Bay is Rainbow Haven Beach, but "one of the largest beaches in North America?" A closer look reveals a cautionary tale of our use and abuse of the natural environment.

Silver Sands Beach, as it is known today, was called Cow Bay Beach until the 1920s. Located directly to the east of Eastern Passage, it was the closest beach to Halifax. It boasted white sands and a picnic area along the adjacent lake. Indeed, it was considered the place to go for a picnic. At the height of its popularity, the beach also had a pavilion, a dance hall, and various canteens. As it was close to the city, people would travel by horse and wagon, even steamboat, to visit in the days before automobiles. Once automobiles were common, the beach only became more popular.

Cow Bay Beach was also promoted internationally for its beauty, particularly to tourists from the northeastern United States. The beach retained its fame from about the 1860s through to the 1960s.

Unfortunately for beach-goers and nature lovers alike, the beach sand and gravel were also popular as construction materials. A construction company began to remove sand and stone from the beach in the mid-1950s. The company claimed it was removing materials in areas unpopular with beachgoers and picnickers, and that wave action over the winter months would restore the lost sand and gravel. Much of the material removed was used in construction projects across Halifax and areas, including the runways at Shearwater and for container piers in Halifax's harbour. Public opposition to the project was strong and did lead to legislation against the removal of beach materials. Unfortunately, these actions were not enough to save the beach--wave action did not replace the sand, and the beach was reduced to a rocky shoal.

In the late 1950s, a series of concrete animals sculpted by New Brunswick folk artist Winston Bronnum decorated the beach. Among them were a turtle, an alligator, and a moose. Today only the 12-foot moose statue remains.

Today, the beach remains a rocky shadow of its former glory and the source of much contention. The beach is a municipal park, but access has been blocked by an adjacent private landowner. A series of court battles have ensued and continue up to the present.

References

-Boileau, J. (2007). Historic Eastern Passage: Including Imperoyal, Shearwater, South East Passage, Cow Bay, McNab's Island, Lawlor's Island, and Devil's Island. Nimbus Publishing.

-Bousquet, T. (2018, June 25). Silver Sands: The Best Halifax-Area beach we ever destroyed. Halifax Examiner. https://www.halifaxexaminer.ca/uncategorized/silver-sands-the-best-halifax-area-beach-we-ever-destroyed/, opens a new window

-Hudak, M. L. (2014). Cow Bay's Ocean Playground: The shifting landscape of Silver Sands Beach, 1860s - Present. [Master's thesis, Saint Mary's University]. Retrieved from https://library2.smu.ca/xmlui/handle/01/25865, opens a new window

-Taylor, R. B. and D. Frobel. Historical changes in Cow Bay Beach, Halifax Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia (2008). Retrieved from https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.821378/publication.html, opens a new window.

-Woodford, Zane (March 2, 2023). Halifax goes back to court over Silver Sands Beach access in Cow Bay. Halifax Examiner. Retrieved from https://www.halifaxexaminer.ca/government/city-hall/halifax-goes-back-to-court-over-silver-sands-beach-access-in-cow-bay/, opens a new window

Halifax Common

The Halifax Common has been part of the city’s landscape for 260 years. In 1763, King George III permanently granted the land to the people of Halifax. “Commons” were a British tradition – space set aside for the public to use freely to pasture livestock or gather firewood. In Canada, the Halifax Common was the first of its kind, and the Common of 1763 looked very different from what we see today. The original Common measured about 95 hectares – picture the area between Cunard Street and South Street, with Robie Street marking the western border and North Park Street, Ahern Avenue, Bell Road and South Park Street to the east. The land at the time was marshy, with small scrubby trees, rocky fields, and a brook running through it.

Over the years, the Halifax Common has hosted many activities and events. The North Common’s close proximity to the Citadel made it an ideal location for military drills and exercises. Horse racing brought crowds to the Common from 1768-1771 (until the drinking, gambling and fighting that accompanied the races led to their cancellation), again from 1825-1845 (along with food and alcohol, music, dancing and card-playing), and finally in the form of harness racing from the 1940s to the 1960s. When the circus came to town, the North Common was a perfect venue. In 1876, P.T. Barnum’s famous circus visited town; it featured exotic animals, hundreds of horses, and performances like a high diving act. Thousands of participants attended, and 500 men were required to set up the tents and pavilions.

On a sad note, the Common held emergency housing to shelter people whose homes were lost to the Halifax Explosion of 1917. Later, it served as the location for visits from the Royal Family and the Pope in the 1980s, Grand Prix auto racing in the 1990s, Rolling Stones and Paul McCartney concerts in the 2000s, and the Membertou 400 powwow in 2010.

The fountain seen in this postcard was built in 1966 as part of a beautification project and still decorates the North Common today.

References

-Boutilier, A. D. (2015). The Citadel on stage: British military theatre, sports, and recreation in colonial Halifax. New World Publishing.

-Cameron, P. (2013). Celebrate the Common 250. Friends of the Halifax Common.

-Collins, L. (1990, October 12). The Commons: Boundaries recall local history. Halifax Chronicle Herald, B6.

-City of Halifax. (1988?). The Halifax Common: Canada’s oldest park [Pamphlet].

-City of Halifax. (1992). Halifax Common background report.

-DeLory, B. (2011). Three centuries of public art: historic Halifax Municipality. New World Publishing.

-Guildford, M. (2003, March 2). Common ground. Halifax Chronicle Herald, C8.

-Littlefair-Wallace, S. (2013, October 3-9). A Common cause. The Coast, 5.

-Nunn, B. (2004). 59 stories: Nova Scotia’s curious connections to the remarkable, the world-famous and the strange. Nimbus.

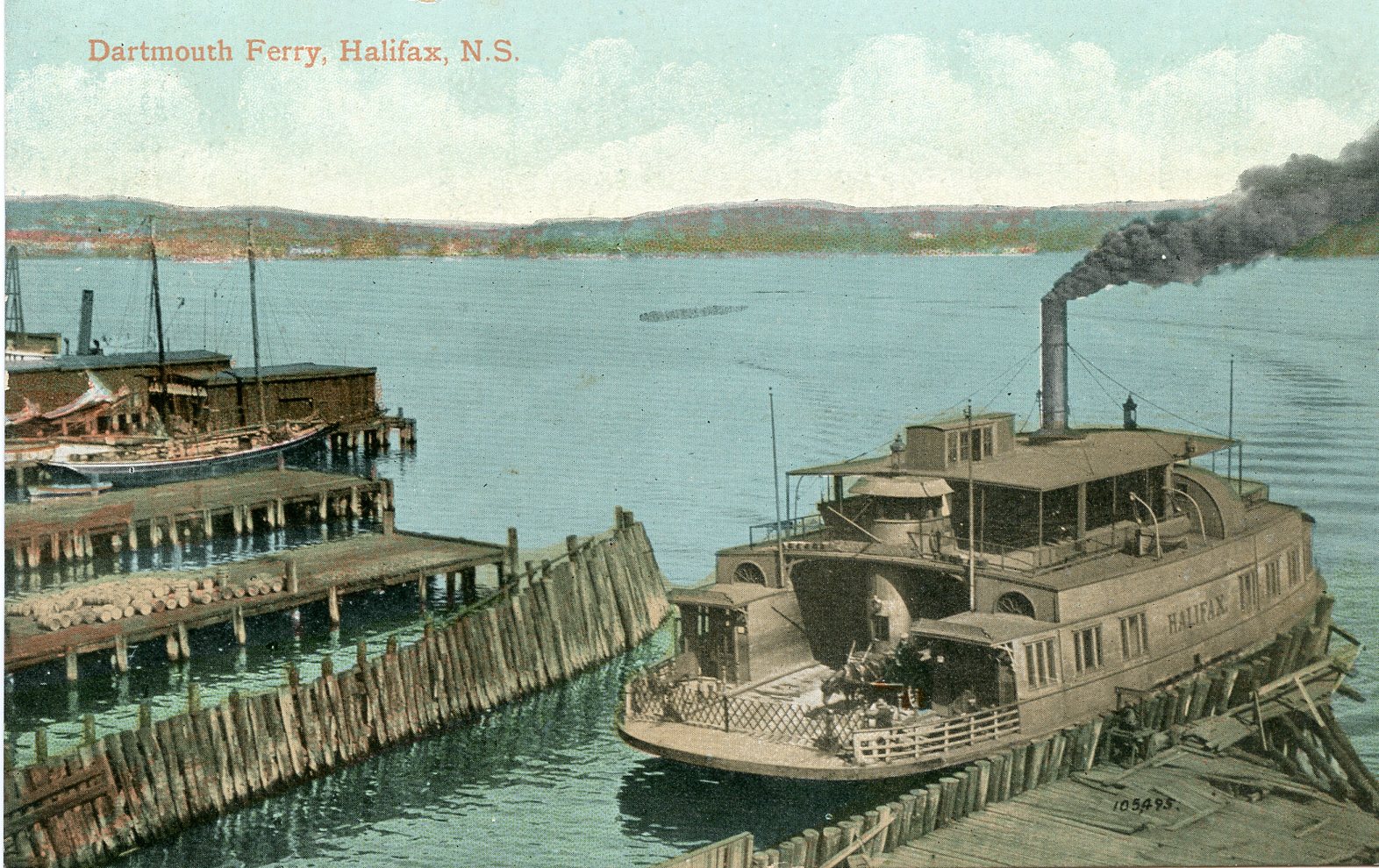

Dartmouth Ferry

The Halifax-Dartmouth ferry is the oldest operating saltwater ferry in North America and the second oldest in the world; the ferry has operated between the Halifax and Dartmouth terminals for 271 years since its establishment in 1752. When the ferry first began operation, it only ran from sunrise to sunset, and only twice on Sundays, once to take people to church services in Halifax and once to bring them back. The adult fare was just 3 cents.

This postcard depicts the country’s first beam engine-powered ferry in Halifax, the Annex II, which was later renamed Halifax. The ship was built in New Baltimore, N.Y., in 1878 and sold to Halifax for $25,000, which today would be about $833,414. It used a beam engine for power, which is a type of vertical piston cylinder water pump-powered steam engine.

The new ship was a wondrous site to behold, and crowds of people flocked to the docks to welcome its arrival in Halifax on an early evening in July 1890. Unfortunately, jubilation turned to tragedy when the crowd rushed out onto the small gangway in their excitement. In the rush, many people fell into the cold waters of the harbour. Immediate action was taken by the ferry crew to rescue the people in the water, but in the chaos, logs were tossed into the water to act as floatation devices and some people were knocked unconscious. Rescue boats and torches finally arrived and were able to save 24 people that night. However, six people perished.

In the following spring, the ship was renamed the Halifax after a new hull was installed. It remained in service until December 1909, when it was set on fire by an arsonist at the Dartmouth dock.

This was the worst ferry accident to occur in Halifax, and since then, there have been only a few minor incidents, like a riot on the ferry after a concert in 1980 and a few cases of people falling overboard. The last reported accident was in 2019, and the swift actions of the ferry crew resulted in a rescue within five minutes. The Halifax transit ferry crews are well trained in water rescue procedures and often can be seen practicing their skills in the Halifax Harbour.

Today, the ferry service between Halifax and Dartmouth terminals makes approximately 100 round trips daily with more than 6,000 passengers. There are three ferry terminals and five vessels currently in service.

References

-Boon, J. (2016). Viola Desmond wins Halifax ferry naming contest. The Coast.

-Dingwell, R. (2017). Vincent Coleman and Rita Joe win Halifax ferry naming contest. The Coast.

-Grayson, S. (1982). Old marine engines. International Marine Pub. Co.

-Jerrett, A. (2019). Ferry passenger rescued from Halifax Harbour after falling overboard. CTV News Atlantic. https://atlantic.ctvnews.ca/ferry-passenger-rescued-from-halifax-harbour-after-falling-overboard-1.4632330, opens a new window

-Payzant, J. (2002). We love to ride the ferry: 250 years of Halifax-Dartmouth ferry crossings. Nimbus Publishing.

-Payzant, J.M., & Payzant, L.J. (1979). Like a weaver’s shuttle: A history of the Halifax-Dartmouth ferries. Nimbus Publishing.

-Woodbury, R. (2013). Ferry tales. Halifax Magazine, 13(3).

The Carleton Hotel

By Marisa

The 263-year-old Argyle Street landmark has been re-christened several times. Built in 1760, ten years after the founding of Halifax, the Carleton is certainly rich in history. The stone house was originally built by the Honorable Richard Bulkeley—a church, government and military leader—who accompanied Edward Cornwallis to Halifax on its founding. Judge Bulkeley named his residence after his close friend Sir Guy Carleton and used the building to house some of the original sessions of Halifax’s vice admiralty court. It was also a place where Bulkeley entertained such notables as General Wolfe on his way to the battle of the Plains Abraham and the Duke of Kent Queen Victoria’s father, who preferred the accommodations there to those of Government House.

When Henry Hezekiah Cogswell purchased the mansion in 1818, he was already well on his way to prosperity. Argyle Street provided ample space for his large family as well as an address of distinction which added to his social status. At the time of Cogswell’s death, Halifax was enjoying a time of peace and prosperity, and the mansion was about to be converted into a hotel, one of the best in the city. The new owner made extensive modifications to the building and expanded to include the two homes immediately to the south along Argyle.

In 1918, the Carleton House underwent a major change of ownership, management, and renovation. The new directors of Carleton House Ltd. commissioned architect Leslie R. Fairn to design a major renovation and consequently establish a flourishing hotel business. For the new Carleton project, Fairn decided on a flat roof with a Mission-style parapet, simple decorative detailing and a stucco facade. More renovations took place in the next decades as the Carleton Hotel changed owners, and by the mid-1970s, the future of the Carleton lay not in lodging but in food and beverage service.

In the early 1990s, the Carleton Hotel was at risk of being demolished. The hotel’s age and condition added to financial problems, caused owners to close the lounge and restaurant and asked the city to have the Carleton’s heritage designation removed. Many voices were raised in concern which led the city, Heritage groups and different organizations to work together to save the building from demolition. The Carleton was eventually resurrected as a residence and meeting place for retired Navy personnel. Today, the Carleton continues to adapt to every period of Halifax’s history, reinventing and transforming itself as a live venue music, event destination and dining place.

References

-Akins, T. B. (2002). History of Halifax City. Dartmouth, N.S. : Brook House Press.

-Conrad, Rick (1994, January 21). Reclaiming the Carleton. The Chronicle Herald/ The Mail-Star.

-Erickson, P. A., & Duffus, G. R. (1997). Carleton House: Living History in Halifax. Halifax, N.S. : Heritage Trust of Nova Scotia/Nimbus Publishing.

-Limited, F. P. C., & Mackenzie, S. (2004). Halifax Street Names: An Illustrated Guide. James Lorimer & Company.

-Sword, Pam (1992, March 23). Battle lines drawn over Carleton Hotel. The Chronicle Herald/ The Mail-Star

Victoria General Hospital

The Victoria General Hospital on South Park Street is a well-established medical institution that has a rich history in Nova Scotia. As part of the consolidated QEII Health Sciences Centre, its importance cannot be overstated. The impact of the services provided over the years here is vast. Not only does it provide care to those in need and respond to emergencies across the province, but it also has been particularly notable for its role in medical research and education globally. The Victoria General School of Nursing prepared professional nurses for over 100 years (until its closure in 1995) with over 5000 graduates. The hospital’s alignment with the Dalhousie Faculty of Medicine has made it an integral part of their education and training.

The Victoria General (or the VG) in the postcard above (date unknown) is a completely different building than the one standing now, although it was roughly in the same area. The original building has a history that extends well before the VG name was adopted. When it was erected in 1859 on the South Common, on what was essentially swamp land, it was the first public hospital in Nova Scotia. It was originally known as the City Hospital. The massive granite and brick structure cost $38,000 to build, and it wasn’t until 1867, almost a full 10 years before it became a full-time operation—once the province agreed to contribute to operating costs. For the next 20 years, it operated as the City and Provincial Hospital and (like now) was purportedly quite difficult to get into. It finally received its familiar name, Victoria General, in honour of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887.

As the years passed, the VG modernized and attracted a broader clientele. By the turn of the century, its mandate included more focus on scientific investigation and advancing medical technology. For instance, the first X-ray machine was installed in 1904, and the first pathology laboratory opened in 1914. By the late 1930s, it was evident that the building was no longer suitable and a new building replaced it in 1948. The new Victoria General Hospital building is the familiar brick building on South Park Street, which may someday soon become history.

References

-Carter, Joan. (2005). Tears, Trials and Triumphs: A History of the Victoria General Hospital School of Nursing, 1891-1995. Glen Margaret Publishing.

-Howell, Colin D. (1988). A Century of Care: A History of the Victoria General Hospital 1887-1987. The Victoria General Hospital.

-McGuigan, Peter. (2007). Historic South End Halifax. Nimbus Publishing Limited.

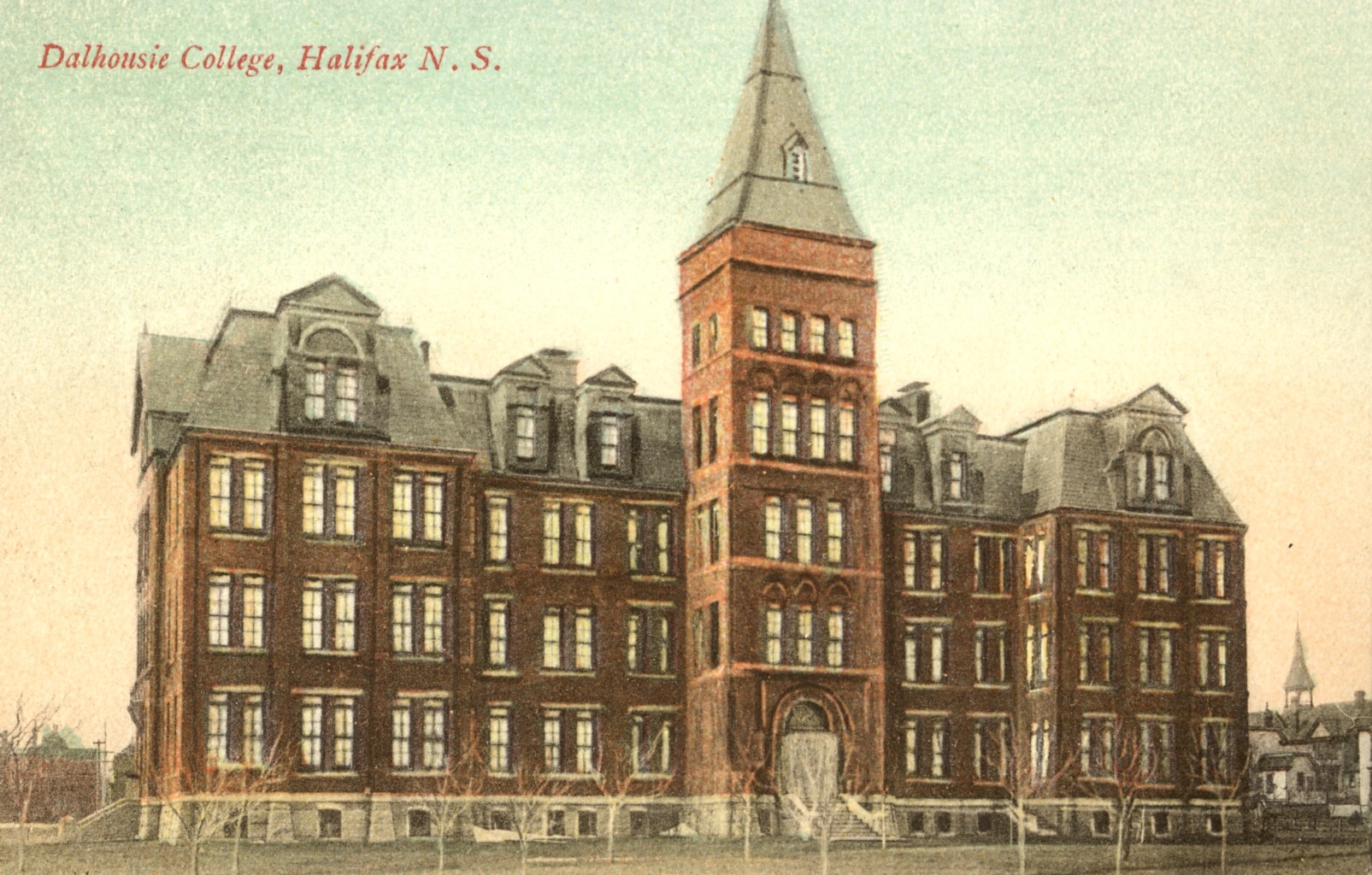

Dalhousie College

Building a school of higher learning was the dream of Lieutenant-Governor George Ramsey, the ninth Earl of Dalhousie. This dream was fulfilled when he used the majority of the customs duties collected late in the war of 1812-14, when British forces occupied Castine, Maine, to establish a college. The new non-denominational college was based on Scottish precedent in Halifax and was founded in 1818.

Dalhousie College was located at the north end of the Grand Parade, where City Hall stands today. Constructed of gray stone, which was later whitewashed, it was Georgian in design. The building consisted of a four-story centrepiece, though at Parade level, only two storeys could be seen. The building had sheltered a museum, debate club, mechanics' institute, a post office, an infant school, and a pastry cook's establishment, as well as professors and students since the cornerstone had been laid by Lord Dalhousie in May 1820.

Unfortunately, the original college was dismantled in 1887. During that period, some governors and the majority of citizens attempted to obtain this central and commanding site for the construction of the new City Hall. The deadlock came to an end in 1886 when Sir William Young generously offered the college $20,000 for a new building if it was constructed on the site given by the city. The cornerstone of the new Dalhousie College was laid by Sir William at convocation on April 27, 1887, in the block between Robie and Carleton streets, now called the Forrest Campus.

References

-Glimpses of Halifax Blakeley, Phyllis R. 971.622 B636g

-Fortress of Halifax: portrait of a garrison town Parker, Mike 971.622 P242f

-Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society, Vol. 2, 1999 page 75-76

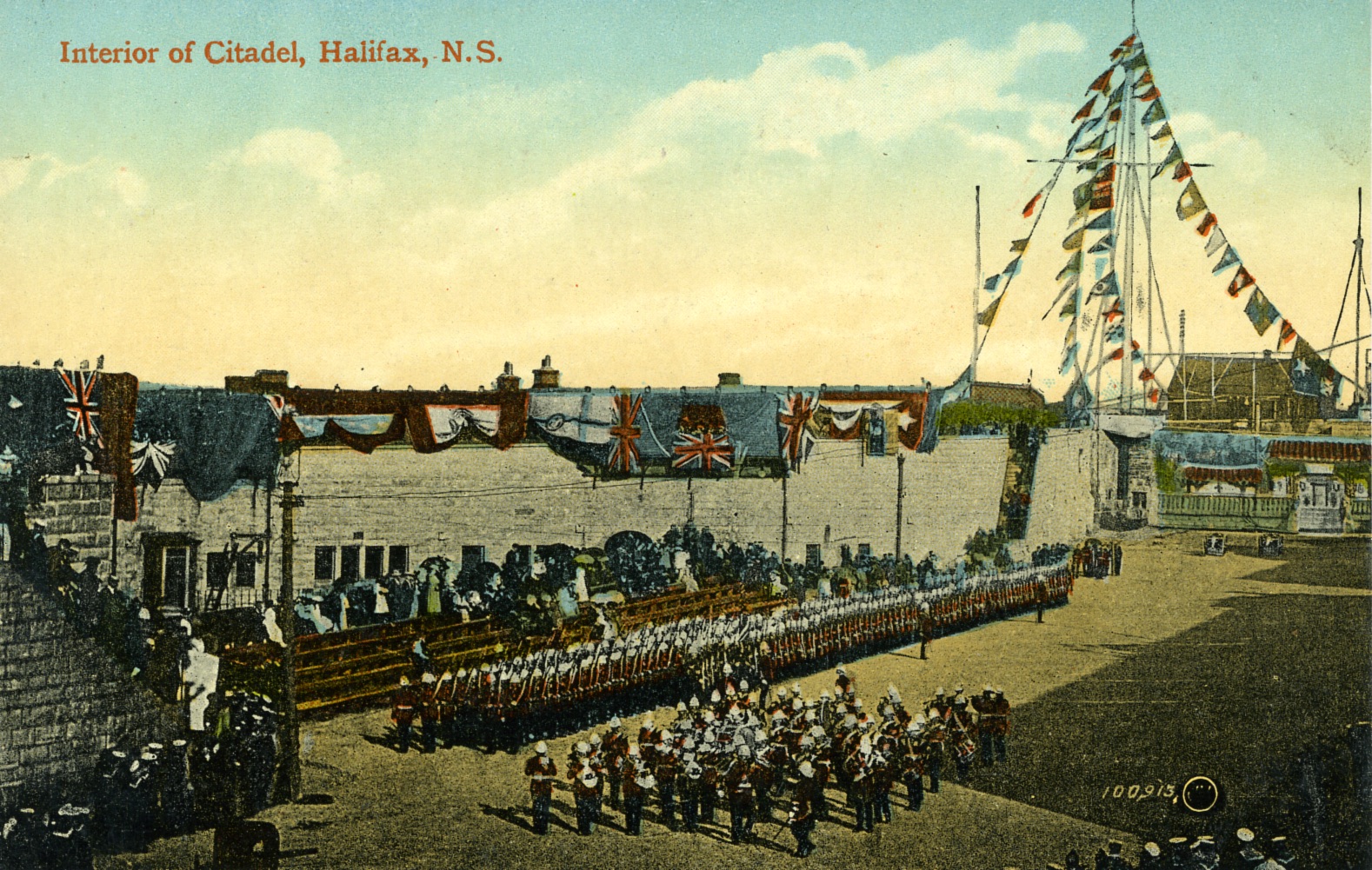

Citadel Hill (Interior)

Written by Katie Houston

The fortification of Citadel Hill began in 1749 with the founding of the city of Halifax and served as one of four major overseas naval bases in the British Empire. The fort was one component of the Halifax Defense Complex that was constructed to defend the city. The first fortification was nothing like what we are familiar with today; it was a small redoubt with only a guardhouse and flagstaff. Since then, the fortification has undergone three expansions. The second was a permanent fort built during the American Revolution; it had a fourteen-gun battery and could accommodate over 100 troops. The third expansion began in 1796 to combat threats from the French Revolutionary War and was completed in 1800. This is the only fortification to be officially given the name of Fort George after King George III. His son Prince Edward was stationed in Halifax as the Commander-in-Chief during this period and was instrumental in the design and construction of the new fortifications and the Halifax Town Clock. The fourth and final fortification of Citadel Hill that we know today began in 1828 and was not completed until 1856. The design was inspired by the designs of Sébastien Le Prestre, Marquis de Vauban. As a military engineer for Louis XIV, he revolutionized the use of citadel bastion forts for more strategic military defence and is regarded as one of the greatest military engineers.

One of the most prominent features of the fort can be seen in this postcard – the Citadel Hill Signal Mast – this 52-meter-tall mast can be seen from a distance of 27km and uses a system of brightly coloured flags, discs and pennants to communicate with other military bases and the public. The mast was used for over 150 years to communicate shipping routes and arrivals of incoming vessels and to inform the public of upcoming traffic in the harbour through a series of flag messages whose code was posted weekly for the public to decipher.

However, the signal mast had another use that the public was unaware of—to communicate with other military bases. These messages were sent between bases using a secret code with the discs and pennants. Managed by the Director of Signals, Halifax Citadel was the base operations for this system of communication with signal posts Sambro Island, Camperdown and York Redoubt. It was the duty of the Director of Signals to ensure that all equipment was in working order, prepare the signals to be sent, and decipher and record incoming signals. These signals would remain in place for no longer than five minutes. While the signal mast is no longer used for military communication, it remains in place with flags and pennants that recreate historic signals as they did in the days before the telegraph became more commonly used.

Today, Halifax Citadel Hill National Historic Site showcases the history of Canada’s military operations. Visitors can enjoy re-enactments of the 78th Highlanders and the Royal Artillery, who wear period uniforms from the 1800s as guards at the entrance of Citadel Hill, as well as conducting marching and band drills on the parade grounds.

References

-Greenough, J.J. (1977). The Halifax Citadel, 1825-60: A narrative and structural history. National Historic and Sites Branch Parks Canada.

-Halifax Citadel: defending a strategic port city. (2000). Times Series (Titanic Times), 1(revised edition), 17-18.

-Johnston, A.J.B. (1981). Defending Halifax: Ordance, 1825-1906. National Historic Parks and Sites Branch Parks Canada.

-McCulloch, I. (1987). The Halifax Citadel: ‘walking talking history’. Atlantic Advocate, 77(7), 40-43.

-Parker, M. (2004). Fortress Halifax: Portrait of a garrison town. Nimbus Publishing Ltd.

-Parks Canada. (2023, June 29). Halifax Citadel signal post. Government of Canada. https://parks.canada.ca/lhn-nhs/ns/halifax/culture/ingenierie-engineering/poste-signalisation-signal-post

-Soucoup, D. (1998). Edwardian Halifax: Postcard glimpses of an era, 1990-1920. Nimbus Publishing Ltd.

-The naval monuments at Citadel Hill Park, Halifax, N.S. (1954). Commercial News, 64.

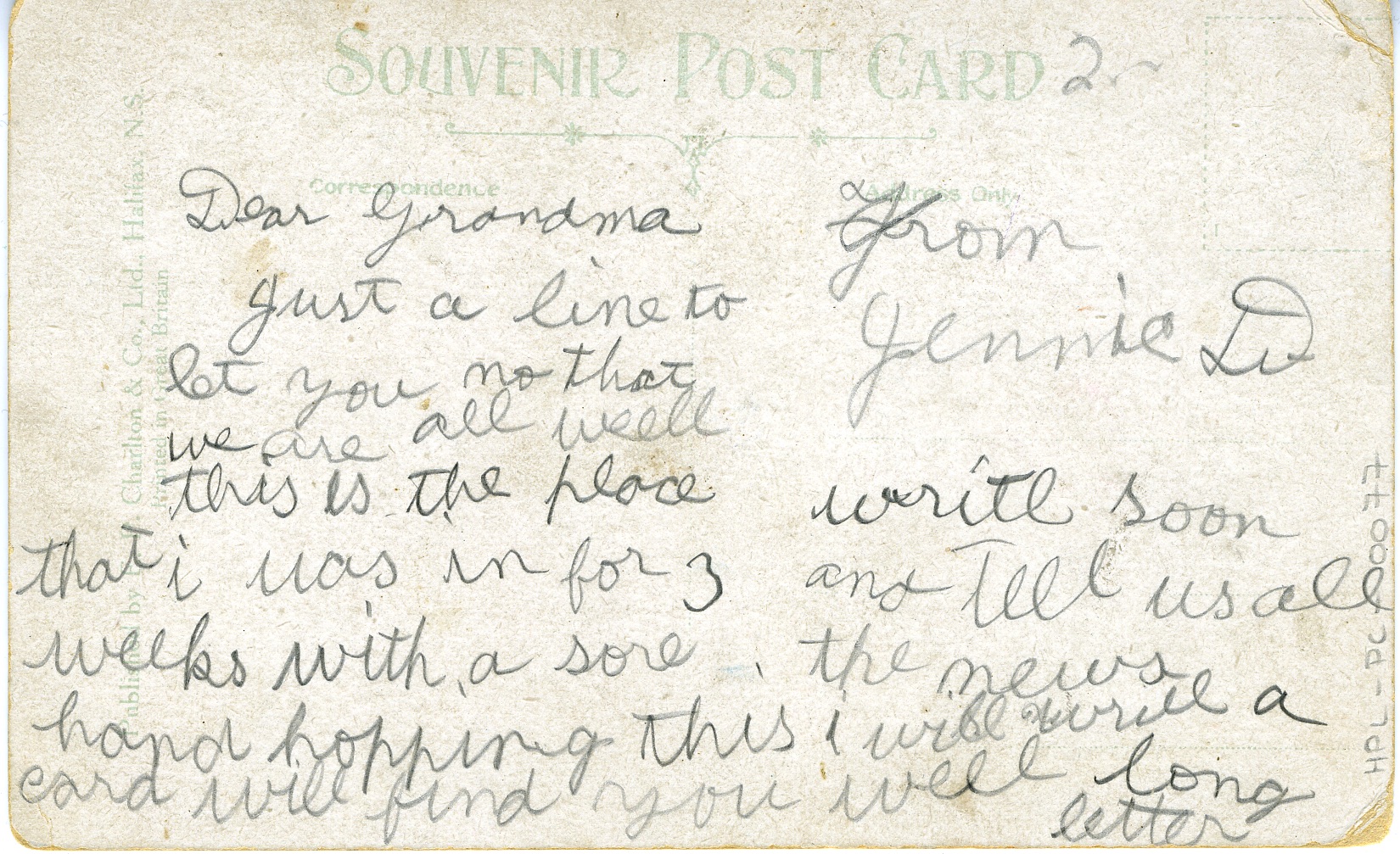

Jolly Tar

Who is this charming fellow?

Beginning in the late 1700s, British naval ships arriving in Halifax and finding themselves short crew members would set officers to the streets armed with cudgels and cutlasses, looking to force anyone suitable into service. These press gangs had only three practical requirements for conscripts: “the man must be alive, between 18 and 55 years of age, and wretched enough to be apprehended” (Prince, 1967). Life on the high seas meant poor pay, little food, and harsh discipline, and often resulted in injury or death; anyone who could, avoided the press gangs at any cost.

To put a more positive spin on this history, Halifax’s “Jolly Tar” was a project of the Tourist Committee of the Halifax Board of Trade. It was initially unveiled on June 27, 1963, with the purpose of re-emphasizing the “heritage of the sea.” The term “Jack tar” is an English term referring to a member of the Merchant or Royal Navy, while “jolly” was adopted from the “Heart of Oak,” the official march of British and Canadian navies.

As it was envisioned, a roving press gang headed by the Jolly Tar (or “Jolly”) mascot would circulate throughout Halifax and “impress” visitors into honorary service. Plans were also underway to create a Jolly Tar Hornpipe, a week-long nautical festival modelled off the Quebec Winter Carnival and Calgary Stampede.

Long-time residents of the city may remember Jolly at various civic events. While there was initially a great deal of enthusiasm about the campaign, it does seem Jolly had a difficult time maintaining membership in his press gang. An article by C. J. Creighton in the April 1965 edition of Commercial News admonished readers that Jolly could attend so many more events if only members of the business community would step up and join the press gang in greater numbers.

Ultimately, the Jolly Tar Hornpipe did not become a regular festival, and Jolly himself was retired sometime after 1973.

The next time you visit the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, look for Jolly’s head in the visible collections storage on the second floor.

References

-Bousquet, Tim. (April 25, 2019). 40 Years Ago, Jolly Tar, A symbol of genocidal Imperialism, was set aside and nobody raised a fuss. Halifax Examiner. Accessed Sept 2023 from https://www.halifaxexaminer.ca/morning-file/40-years-ago-jolly-tar-a-symbol-of-genocidal-imperialism-was-set-aside-and-nobody-raised-a-fuss/

-Halifax Chamber of Commerce (August 1963). Jolly Tar – Halifax. Commercial News.

-Halifax Chamber of Commerce (December 1963). Jolly Tar wins national award. Commercial News.

Creighton, C. J. (April 1965). Jolly Tar. Commercial News.

-Halifax Chamber of Commerce (April 1973). Board of Trade Week 1973. Commercial News.

-Prince, J. (July 1967). “The story behind the press gang--Part one. Commercial News. Halifax Chamber of Commerce.

-Prince, J. (August 1967). The story behind the press gang--Part two. Commercial News. Halifax Chamber of Commerce.

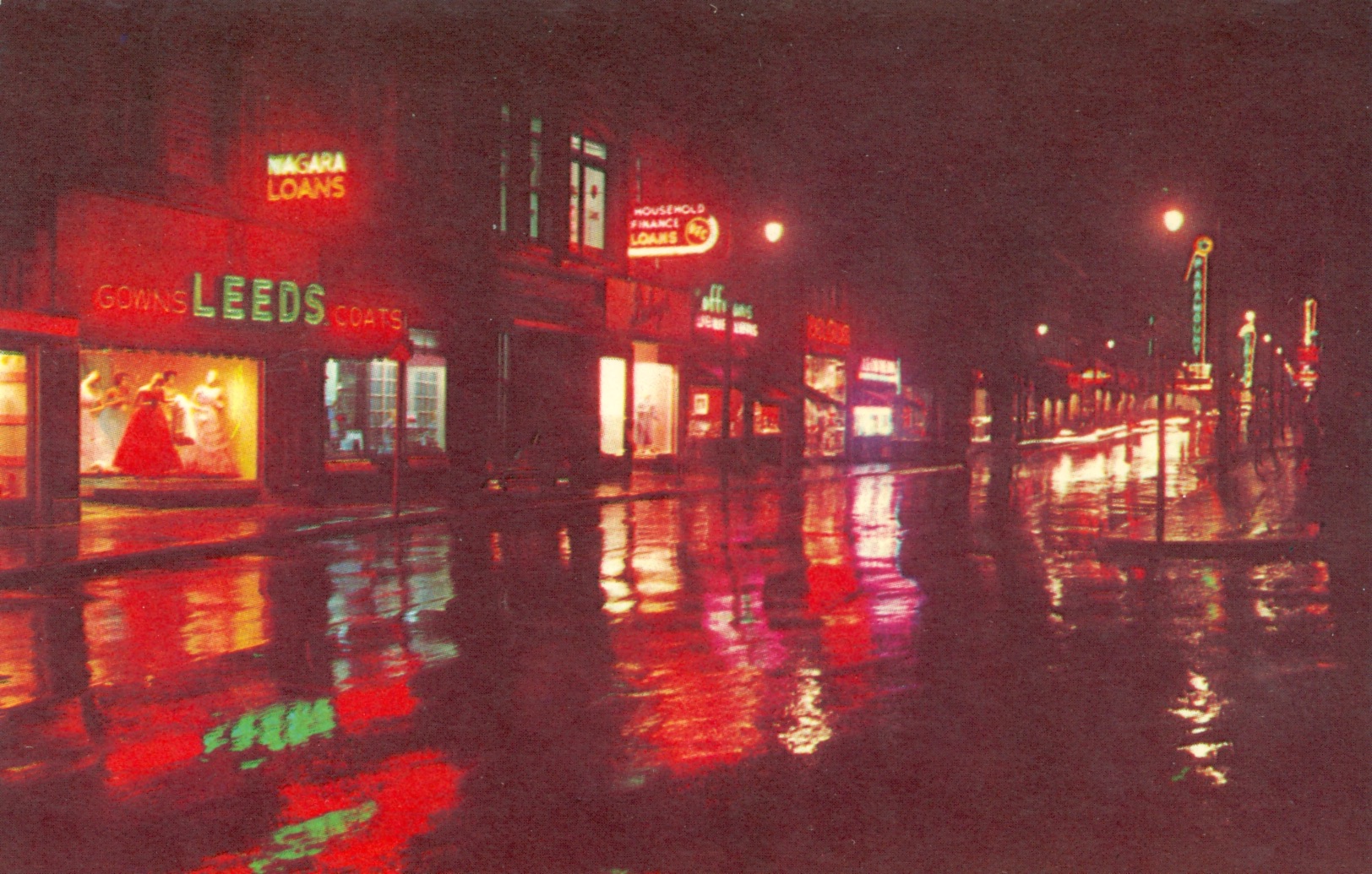

Barrington Street

Barrington Street has a long history in Halifax and has undergone many transformations. Running through the city’s downtown, it travels past Inglis Street in the South End to Africville Park in the north. In 1749, Barrington was laid out by surveyor Charles Morris. It’s named for William Wildman Barrington, the second Viscount Barrington of Ardglass, although the original intention may have been to name the street in honour of the Earl of Harrington. Barrington Street was initially much shorter, and today’s Barrington incorporates what was once Pleasant Street to the south, and Lockman Street and Campbell Road to the north.

In Halifax’s early days, much of the city’s commercial activity took place near the waterfront – streets further north of the water, like Barrington, were mostly residential. At the time, the street featured many single-family homes and gardens. Running past Grand Parade, St. Paul’s Church and the Old Burying Ground, Barrington also has a history of ceremony and display, and Grande Parade once acted as a drilling ground for garrison troops and the militia. In the late 18th century, sedan chairs could be hired by those who wanted to travel with ease and avoid the mud on Barrington Street, which was still unpaved at the time.

As the years went on, the character of Barrington Street changed. Cobblestones were laid, and later asphalt and concrete. Transportation shifted from sedan chairs and horse-drawn carriages to street cars pulled by horses, electric tramcars, and finally, buses and automobiles. Over time, Barrington transformed from a primarily residential street to a commercial centre. The street expanded, merging with Lockman Street in 1871 and eventually Campbell Road, and becoming Halifax’s principal north-south thoroughfare. During the first half of the twentieth century, Barrington was a prime destination, busy with department stores, offices, restaurants and entertainment like the popular Capitol Theatre. Sadly, in later years, the once bustling street began to decline. Contributing to the street’s struggles were the opening of shopping malls in the mid-20th century, the retail shift toward Spring Garden Road in the 1980s, the growth of Bayers Lake Business Park, and the advent of the Cogswell Interchange.

References

-Campbell, M. (February 1996). Reflection and speculation on Barrington St. Southender, 15(2), 8-9.

-Erickson, P. A. (2004). Historic North End Halifax. Nimbus.

-Knox, C. (2008). Past and future. The Coast, 15(47), 17-18.

-Mackenzie, S., & Robson, S. (2004). Halifax street names. Formac Pub. Co.

-Nova Scotia Department of Tourism and Culture, & The Mary E. Black Gallery. (1993). Barrington Street: A walk through time.

-Pacey, E. (1988). Historic Halifax. Hounslow Press.

Superintendent's Lodge, Point Pleasant Park

Located at the southern point of the Halifax Peninsula, Point Pleasant Park is a public park owned by the Halifax Regional Municipality. The land was leased from the Canadian Government for 999 years with a rental price of one shilling annually. Its location provides easy access for approximately 250,000 residents and visitors to get away from the hustle and bustle of the city and enjoy all the natural splendour the park has to offer. The 80 hectares of land include mixed woodland, beaches, historic forts, a pond, gravel roads and woodland paths. Point Pleasant Park was originally the site of small fortifications designed to protect the Halifax harbour in the event of a military attack on the city. It was one of several battlements around the city, which can still be seen today.

Included in the park lease was the use of the Cable House on Pleasant Street for the park superintendent; however, the dwelling was deemed unsuitable for habitation, and it was decided in 1896 that a new home would be built for the superintendent. Maritime architect James Charles Dumaresq was selected to plan and build the home for the sum of $3500. Dumaresq designed the gatehouse as a gothic storybook English revival and constructed the building using Nova Scotia tan sandstone and local ironstone. Despite the unique architecture and design, this is not a one-of-a-kind home; it is modelled after the Wycombe Lodge in England—the home of former British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli[A1]. By 1897, the house was complete, and the first superintendent, Samuel Venner, moved in. He lived there until his death in 1906.

Over the years, the gatehouse in Point Pleasant Park was home to eight superintendents, survived the Halifax Explosion with minor damage, and was upgraded with indoor plumbing and electric lights. An addition was eventually built on the gatehouse in 1948 using stone from the Cambridge Battery. Since the formation of the Halifax Regional Municipality in 1996, the Superintendent’s Lodge has not been occupied, but it remains a part of the history of Point Pleasant Park and a reminder of all the superintendents who cared for the park over the years.

References

-Johnson, W.L. (1989). Forest renewal action plan point pleasant park. W.L. (Slim Johnson Forestry Consultant Ltd.

-Kalman, Harold. (2000). A concise history of Canadian architecture. Oxford University Press.

-Kitz, J., & Castle, G. (1999). Point Pleasant Park: An illustrated history. Pleasant Point Publishing.

-NIPpaysage Ekistics Planning and Design. (2008). Point Pleasant Park comprehensive plan.

-Page, W. (1925). A history of the County of Buckingham Volume 3: Parishes Hughenden. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/bucks/vol3/

Acadian Lines

The familiar Acadian Lines buses crossed Nova Scotia for almost 80 years—from 1938 to 2012. Founded in 1938 as Nova Scotia Coach Lines, the company started as part of a Maritime gas station, car dealership, and appliance chain. Soon after, the company name was changed to Acadian Coach Lines, both to reflect the local heritage of Nova Scotia and to be at the top of the phonebook! The company started with just four buses but grew quickly the business over time. The original buses had fewer seats, carried passengers’ luggage on the roof, and did not provide washrooms or air conditioning.

Over the years, Halifax passengers departed for their bus trips at four different bus terminals. The first passengers in 1938 waited near the Lord Nelson Hotel on Spring Garden Road. In 1943, Acadian Lines moved to a small bus terminal on Dresden Row. By about 1963, the company expanded to a larger and more modern bus terminal and headquarters on Almon Street. The final Halifax Acadian Lines bus terminal opened in 2002 at the Via Rail station on Hollis Street.

Acadian Lines moved more than passengers–they delivered packages and medical necessities such as blood. Community service was also important to the company, and they demonstrated this by offering free bus service for senior citizens on their way to the Nova Scotia Tattoo in Halifax or Christmas shopping, and to children attending Rainbow Haven.

After almost 80 years in service, Acadian Lines (then owned by a Quebec Company) ceased service in 2012, citing financial loss. Up to 47 communities across Nova Scotia, PEI and New Brunswick had been connected by the bus service, which served up to 500,000 passengers per year.

City Hall

One of Halifax’s greatest historic buildings is undeniably City Hall, situated on the north end of Grand Parade in downtown. It once stood above all the other buildings in the city center with its seven-storey clocktower for all to see. Now, as the city buildings have been built taller and taller, the visual impact of the building may have diminished, but its importance and legacy have not.

In the late 1800s, Halifax was growing and it was obvious that city affairs could no longer be handled in the courthouse’s cramped quarters on George Street. City officials really wanted to obtain the land on Grand Parade, where Dalhousie College stood to build a new city hall. After much negotiation, a deal was struck with the government, Dalhousie was moved, and the college building was demolished.

The new city hall building was designed using the popular Second-Empire architectural design with cream and red sandstone, as well as granite exterior. It was a thoroughly impressive building inside and out, and finally, Halifax had the city hall that it deserved. The building opened on May 2, 1890, with a grand celebration.

The new City Hall had space for traditional facilities, including the mayor’s office, city department offices, and the Council chamber. It also provided space for other city functions. The Citizens Free Library finally got a permanent home here that year on the second floor (the library remained here until the Spring Garden Road library opened in 1951). Also, the police station and city jail were relocated there until 1952. In fact, in 1896, the young magician Harry Houdini, who had been touring Nova Scotia and New Brunswick all summer, performed a series of handcuff escapes at City Hall. His final stunt involved breaking out of a jail cell, although nobody seemed to know or care at the time.

Over the years, the building had some issues, mainly involving repairs and renovations. Surprisingly though, it withstood the Halifax explosion with minimal damage. The following year, though, it was seriously impacted by a riot. Following many projects and numerous renovations, City Hall continues to watch over the city as it has since 1890.

References

-Blakeley, Phyllis R. (1973). Glimpses of Halifax. Mira Publishing.

-City Hall History Outlined. (1957, January 18). The Halifax Mail-Star.

-Cuthbertson, Brian. (1999, Volume 2). History of the Grand Parade and Halifax City Hall. Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society Journal.

-DeLory, Barbara. (2016). Historic Halifax Streetscapes Then and Now. New World Publishing.

-McNab, Bruce. (2012). The Metamorphosis: The Apprenticeship of Harry Houdini. Goose Lane Editions.

-Nickerson, Alex. (1987, August 11). City Hall Site of Controversy. The Halifax Mail-Star.

Jubilee Fountain

If you should find yourself strolling in the Halifax Public Gardens anytime—on your lunch break or waiting for an appointment—take a look at the Jubilee, or Nymph, Fountain that's in the northwestern section of the garden.

The fountain was designed in New York by the eminent J.W. Fiske Company more than 100 years ago, in 1897. It was made to commemorate Queen Victoria's sixty-year reign from 1837 until 1897. The fountain was shipped to Halifax and arrived at the Irving Arch Wharf, Lower Water Street, on June 6, 1897.

The metal nymph fountain is stunning and classical in style. The center stem rises from a base in the form of a Corinthian column surrounded by four smiling bronze cherubs. From each corner, a cherub takes our imagination on a sea serpent ride through splashing water. At the top stands the nymph Ergeria in a loose garment, accompanied by four cherubs riding on sea serpents, tipping a jug of water into perpetual bulrushes surrounding her.

The fountain was unveiled by the Countess of Aberdeen on Thursday, June 24th, 1897. The unveiling had been planned for Monday, June 21st, but was postponed by rain. As you gaze at the eighteen foot cast iron fountain, imagine that beautiful sunny Thursday morning when representatives of all levels of governments, First Nations members in traditional costume, citizens and visitors to the city gathered for the debut. They listened to a six-hundred-voice choir and watched Lady Aberdeen try, fail and then, with the assistance of her husband, uncover the two-thousand-dollar monument as the children sang "Victoria."

The fountain has been a joy and delight to generations of citizens and visitors. It was renovated in 1983-84 and restored to its previous glory. It continues to refresh visitors to this day, over 100 years later.

References

-DeLory, B. Three Centuries of Public Art: Historic Halifax Regional Municipality, pp. 85-87.

-Friends of the Public Gardens. The Halifax Public Gardens, pp. 22 & 60-61.

-Nova Scotia Archives and Record Management. Halifax and its people 1749-1999: Images from Nova Scotia Archives and Records Management, p. 80.

-Shutlack, G.D. City Rambles No.2 - Halifax Public Gardens Jubilee Fountain. The Griffin. Vol: 18. No. 1/March-May 1993, p. 6.

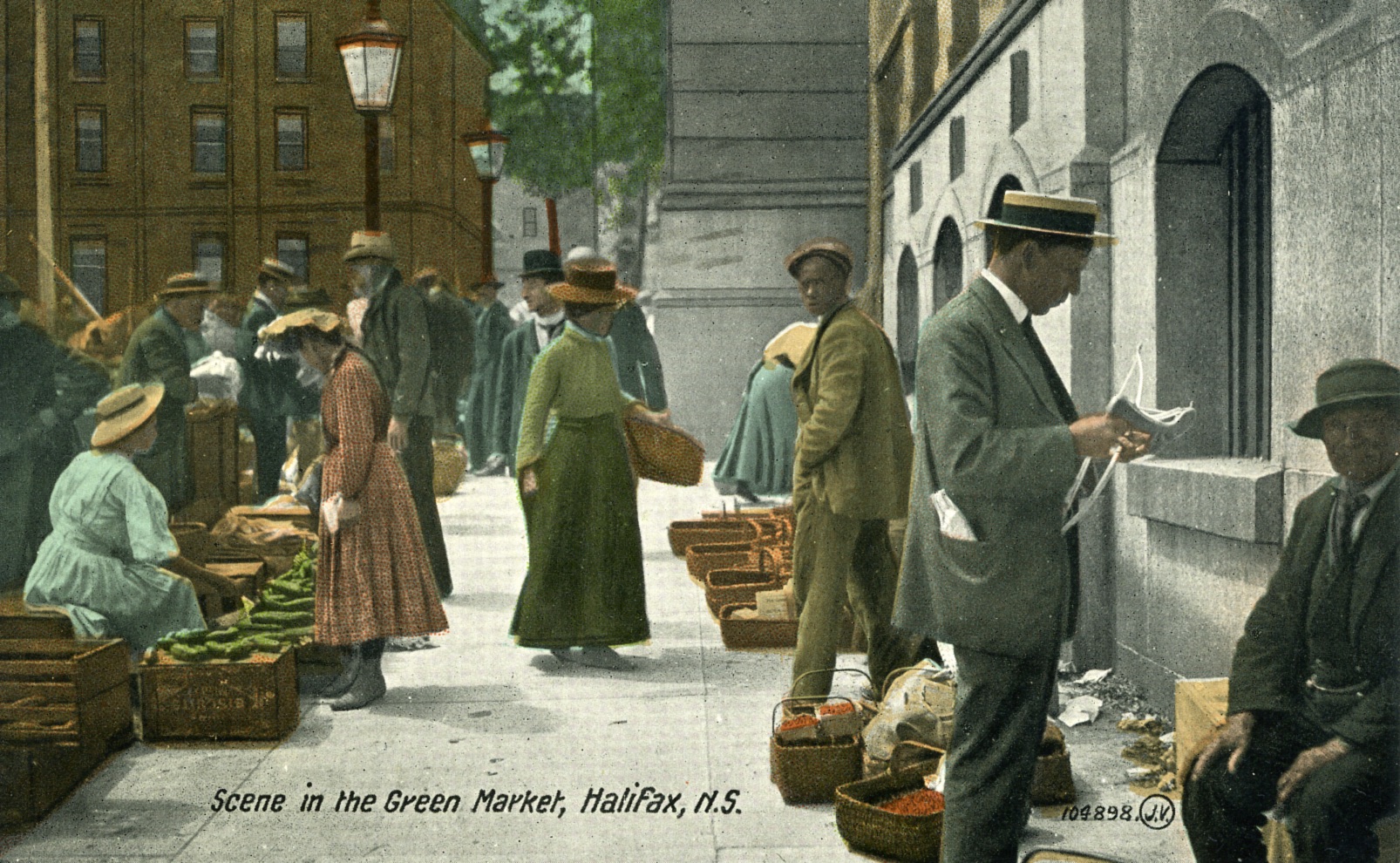

Green Market

Throughout its history, Halifax was known for its bustling Green Market, also known as the Cheapside Market. There had also been a market in the city dating back to 1750 that sold meat and produce; and a market building was constructed in 1854, but country vendors refused to use the new building and preferred the street location.

Pictured here in 1907, this street market was popular with residents and tourists, and hundreds visited each week. The outdoor market was set up along Bedford Row to George Street every Wednesday and Saturday morning.

Vendors from rural areas would bring their goods into the city to sell. Produce, eggs, and butter were available, as well as Christmas trees in the winter and mayflowers in the spring. However, nearby merchants took issue with the litter left behind in the market’s wake and complained that market traffic disrupted business.

In 1916, the city opened a new building on what’s now called Market Street to replace the Green Market. In response to vendors’ resistance to the change, the city provided them with opening day refreshments and two weeks’ free rent – as well as a police escort to the new location.

The streetside Green Market disappeared by 1921, and later, the market building was torn down to make way for Scotia Square.

References

-Old Green Market Here was Colorful Spectacle (1956, April 23). Halifax Mail Star.

-Kilcup, K. (Ed). (1998). Halifax Farmers Market: Chasing the dawn. City Market of Halifax Cooperative Limited.

-Biesenthal, L. (1980). To market, to market: The public market tradition in Canada. PMA Books

Steel's Pond

"They paved paradise to put up a parking lot" –Joni Mitchell

This view and this pond no longer exist in Halifax.

Pleasant Street, now renamed Barrington Street, at one time ran directly from downtown Halifax and ended in current-day Point Pleasant Park. The street was considered a very fashionable street for promenading, to see and be seen, as it were. Residents could stroll along the waterfront from the city proper, across the former Freshwater Brook, through the community of Greenbank, and into Point Pleasant Park.

The view in this postcard is of the bottom end of Pleasant Street. To its right, you can see a pond pictured, known as Steel’s Pond. Steel’s Pond was a real favourite among Haligonians for skating; indeed, “perhaps the best known of the south-end ponds was [Steele]'s Pond,” according to Halifax historian and author Lou Collins (Stevens, 2016).

All this would change as Halifax strived to be a bigger player in the shipping industry and wanted to accommodate ever larger ships. In 1912, engineer Frederick Cowie was commissioned to examine the harbour and ways to expand it. Cowie’s report identified the land south of the city center as the most ideal space to build new ports. He stated that the land was largely undeveloped and unoccupied, both statements belying reality.

With the construction of the Ocean Terminals, the south end of Pleasant Street was largely destroyed, and what remained was cut off from the city. At the same time, stone from the concurrent rail cut project was used to infill the harbour, expanding the peninsula further. Steele’s Pond was buried underneath a parking lot.

When you visit Point Pleasant today, don’t “take the parking lot at face value; the asphalt that greets you between the container port and Point Pleasant Park is the ghost footprint of Steel’s Pond and the pathway of Pleasant Street.” (Campbell, 2020).

References

-Campbell, Claire (January 2020). Whatever Happened to Pleasant Street? Rediscovering an Urban Shoreline. Environmental History, Vol. 25, no. 1. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/envhis/emz060.

-McGuigan, Peter. (2007). Historic South End Halifax. Nimbus Publishing: Halifax.

-Stevens, Ryan. (2016, January 19). Halifax's Skating History (Part Three, Pond Skating). Skate Guard: The Ultimate Guide to Figure Skating’s Fascinating, Fabulous and Festive History. Retrieved from skateguard1.blogspot.com

Dartmouth Shopping Centre

The Dartmouth Shopping Centre opened with a splash in 1956. The Angus L. Macdonald Bridge had been constructed the year before, and the shopping centre was designed to capitalize on the sales potential of this new Halifax-Dartmouth connection. Located near the bridge's eastern end at the intersection of Wyse Road and Nantucket Avenue, it had a bus stop out front, making it easily accessible for Halifax shoppers.

Modern, shiny, and the largest shopping centre in the Maritimes at the time, it was owned by Maxwell Cummings and Sons and cost 1,500,000 dollars to construct. At opening, it housed about twenty stores, including Dominion Super Markets, Zeller’s, Leon Neima, Dalfen’s Department Store, Lawtons Drug Store, and Western Electrics. The open-air mall was designed in a U-shaped design, with covered walkways and music playing from a state-of-the-art system to create a pleasant shopping experience. Featuring a parking lot that could accommodate 3,000 cars each day, the mall’s slogan was “One Stop to Shop.”

The grand opening took place on March 15, 1956, with shoppers enticed to visit with gifts, prizes, and an appearance by the Ice Ca-pets from the International Ice Capades Show. Shoppers could enter a draw for a 21-inch General Electric television set, and many stores had opening giveaways, like “free orchids for the ladies” at Dominion and a complementary bone china cup and saucer to the first 1,000 shoppers at the Leon Neima store. Nearly 30,000 people attended the opening event.

In later years, the Dartmouth Shopping Centre was bought and sold many times and underwent two major renovations. In the early 1970s, Trizec Equities purchased the shopping centre and restructured it to create an enclosed mall. Twenty years later, the tides turned again. The Dartmouth Shopping Centre was waning in popularity and experiencing high tenant turnover. It was purchased by Larex Scotia in 1994, who spent 2.5 million converting it back into an open-air strip mall. Although the Dartmouth Shopping Centre has changed hands a few times in the years since, it remains today, like its original design, an open-air shopping experience.

References

-Bousquet, T. (2015, August 31). Who sold off the Dartmouth Common? Halifax Examiner. https://www.halifaxexaminer.ca/government/city-hall/who-sold-off-the-dartmouth-common/

Bridge completion brings start on Dartmouth Shopping Center. (1955, May). The Maritime Merchant, 17, 28.

-Dartmouth Shopping Centre back in local hands after sale. (2004, January 14), The Daily News, 17.

-Dartmouth Shopping Centre celebrates 25th anniversary. (1981, May 26), The Mail-Star, 26.

-Leon Neima opens new store in Dartmouth. (1956, March 14). The Halifax Chronicle-Herald, 41.

-Power, B. (1994, May 14). Dartmouth mall to get overhaul. Halifax Chronicle Herald, A1, A2.

-Taylor, R. (1994, October 18). New mall owner returns to basics. Halifax Chronicle Herald, B1.

-Various advertisements (1956, March 14). The Halifax Chronicle-Herald.

-Warrington, I. (1956, May). New shopping center opened in Dartmouth. The Maritime Merchant, 20–21, 33.

Halifax Armoury

The Halifax Armoury is truly a formidable building.

It is located on North Park St. at Cunard, facing the Common. The rock-faced red sandstone building is one of the oldest and most prominent landmarks in Halifax, built between 1896 and 1899. The new armoury building was unique at the time and has played a vital role in Halifax's rich history.

The Armoury was designed by Thomas Fuller, Chief Architect for the Dominion of Canada, to give a castle-like and imposing appearance. Its two-foot-thick walls can withstand massive force, and the towers loom overhead. The building was intended as a drill hall for the militia stationed in Halifax. It is one of the best examples of government initiatives undertaken at the end of the 19th century to build militia practice, training, and recruitment centers and remains one of the only ones still in use.

Drills have always been important in military training. In Halifax, a large sheltered area was essential—especially in winter—so the Armoury seemed perfect. It was put into service right away as Canada supplied troops after the Boer War broke out in 1900. After the Halifax Explosion in 1917, it was used to shelter those left homeless. Again, in 1945, it was used as a shelter after the Bedford Magazine Explosion.

Over the years, the building has also been used for civilian events, including concerts and dances. It also serves as a landmark and a memorial to those who trained there over the years.

The Armoury was designated a national historic site in 1989 and a Federal heritage building in 1991, both due to its historical and architectural significance. The structure was originally built and furnished for $250,000. Currently, it is undergoing a two-phase renovation. The estimated cost is $160,000,000, and the completion date is 2028.

References

-The Armoury and the Common by Margaret L. Perry. The Atlantic Advocate, September 1984.

-Halifax Armouries: A Vital Part Of The City’s Military History by Harry Chapman. Tour Of Duty, March 2007.

-Halifax Armoury restoration $30M over budget, three years behind schedule by Paul Smithers. CBC News, October 25, 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/halifax-armoury-restoration-progress-overruns-1.6221485

-The Halifax Military Establishment by John Hawkins. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Goldcloth Publishing, 2000. Historic Halifax by Elizabeth Pacey. Willowdale, Ontario: Hounslow Press, 1988.

Women’s Council House

When you pass this large cream and red house on the corner of Young Avenue and Inglis Street, you may not think about its history or connection to the Titanic.

The house consists of eleven spacious rooms and features a beautiful three-story turret and a large glassed-in sunroom. There is a fireplace in almost every room, and many rooms display beautiful blue & white tiles and built-in mirrors.

The house was built in 1902 for the wealthy and successful Haligonian philanthropist George Wright, who sadly perished on the Titanic's maiden voyage. On April 9, 1912, Wright wrote a will bequeathing a large part of his estate to charitable causes on the day before he departed for New York on the Titanic. The Wright house was gifted to the Halifax Council of Women, an organization he admired. When the house was formally handed over to the Women's Council in December of that year, it was chosen as the headquarters and meeting place for the Council.

The Halifax Council of Women is a local branch of the National Council of Women established in Canada in 1893. The Countess of Aberdeen, the wife of the Governor-General of Canada, was the first president and remained in office for 36 years. The Council’s primary purpose is to improve conditions for women and children. By the mid-1950s, the Council of Women in Canada had a membership of 600,000 women. It continues to influence local, provincial, and federal governments to improve conditions we now take for granted, among them supervised playgrounds for our children. Today, the house is also rented out for a reasonable fee as a meeting place for community members who do not belong to the Council of Women.

References

-Historic Halifax Pacey, Elizabeth p.18 971.622 P115hi

-Vertical file: Halifax, N.S. -- Historic Houses

-The Griffin, Vol. 21, No. 2 1996 p.8

Jollimore Settlement

If you look across the Northwest Arm from the Halifax peninsula towards Sir Sandford Fleming Park, you will see the community of Jollimore. While largely absorbed into suburban Halifax today, the community was once bustling with quarriers, stonemasons and later cottagers, and had its own grocery store, post office, churches, a school, and cemetery. Despite its proximity to the city, the area has a tucked-away, secret feel to it—many long-time Haligonians are themselves unfamiliar with the area. Jollimore maintains much of its cottage-like feel to this day.

The first permanent settlers in Jollimore descended from foreign Protestant families who first settled in Lunenburg in 1753. The Slaunwhites (Schlagentweits) were of German descent, while the Jollimores (Jolimois) and Boutiliers were French-speaking Lutherans from Montbeliard in France.

As early as 1821, Martin Slaunwhite came to the North West Arm from the Head of St. Margaret’s Bay to quarry stone. He encouraged his sister Sophie and her husband John George Jollimore to move to the area. They purchased the land now named Boscobel on the Arm and Boulderwood.. Other Jollimore, Slaunwhite, and Boutilier families were drawn to the area by familial ties—and the stone available. The handiwork of these families of stonemasons can be seen throughout the community today.

Early on, Jollimore village was known as the North West Arm Settlement or Lower Arm Village. The community became officially known as Jollimore Settlement in 1902. Quarrying stone was a major draw to the area, but it quickly became apparent that money could be made from renting cottages to affluent Haligonians who were looking for a reprieve from the busy city. Many of the houses in the community were built expressly as cottages and the community had its own summer residents for many years. Several of the homes along Parkhill Road heading down to the Dingle Tower today were cottages built by the Jollimore family for rental income.

In addition to traveling by foot or by vehicle, Haligonians had access to Jollimore and Sir Sandford Fleming Park by means of a ferry service. The ferry was run by the Jollimore and Boutilier families as well as, briefly, Mont’s Oil. The ferry service operated from the 1880s through until the mid-1960s.

This postcard dates from the early 1900s. To the left, one can see some buildings that make up the Finntigh Mara estate, recently the site of an unsuccessful condominium development, while to the right one can make out a church—St. Augustine’s Anglican Church. The group of buildings on the right are the Jollimore family boatyard, later the site of the popular Ken’s Canteen through the 1940s and 50s, now the site of the Dingle playground and parking lot. The forested area further to the right is part of today’s Sir Sandford Fleming Park.

Sir Sandford Fleming, the “Father of Standard Time,” owned property in the area, and donated the land that would become Sir Sandford Fleming Park. Additionally, he donated the land for St. Augustine’s Anglican Church in 1896. The bell for the tower came from the old fire engine house on Spring Garden Road. The congregation outgrew the space in 1964 and it was repurposed into today’s Adventure Earth Centre. In an old co-operative store, members of the community met to inaugurate Parkhill United Church in 1951.

William Cunard purchased land from John Martin Jollimore for the purpose of erecting a school, aptly named Cunard School. The school operated from the mid-1860s until it was torn down in 1893. Unless their parents could afford to send them to Spryfield, the children of the community had no access to schooling for close to ten years until the new Cunard School was operational in 1902. That school burned down in 1915, to be succeeded by yet another school that also burned down in 1947. Today, the site of those schools is a playground, Jollimore Park Playground, where the remains of the final school’s foundation can still be found.

References

MacLeod, Malcolm (2014). A Halifax Boyhood: Growing up on the City’s Outskirts in the 1940s and 50s. Halifax, NS: Formac Publishing.

Mainland South Heritage Society and CRABapple Mapping Project (2002). Jollimore Walk [Brochure].

McInnis, Donna (June 2011). The Pool House in Jollimore: Uncovering the Mystery of this 19th Century House. The Griffin.

Morris, Janet (Sept 2013). Iris Shea: Foreign Protestant Descendants at the North West Arm. The Griffin.

Shea, Iris V. (2000). .“Old Cunard School, Jollimore.” Discovering our Past From Armdale to Pennant: A Series of Articles Compiled by Iris V. Shea for Mainland South Heritage Society, Vol. 1.

Shea, Iris V. (June 2002). “Historic Jollimore-Quarrying Attracted Early Settlers to the Northwest Arm.” Chebucto News.

St. James United Church (n.d.). Our History – Parkhill United Church. Retrieved from https://www.sambrojollimorepc.com/our-history-parkhill

Watts, Heather and Michele Raymond (2003). Halifax’s Northwest Arm: An Illustrated History. Halifax, NS: Formac Publishing.

Withrow, Alfreda (1999). One City—Many Communities. Halifax, NS: Nimbus.

Hubbards, Nova Scotia

In this peaceful scene, a group of boaters enjoys a fine day on the water at Hubbards, Nova Scotia. Hubbards is situated on St. Margaret’s Bay, at the boundary of Halifax and Lunenburg counties.

Originally, the Mi’kmaq hunted and fished in the St. Margaret’s Bay area during the warmer months and set up summer camps there until the early 1900s. By the first part of the nineteenth century, a small number of European settlers were living around Hubbards (called Hubbards Cove until 1905). Fishing and lumbering were the primary trades for the early settlers. Given Hubbards’ beautiful scenery and abundant natural resources, it’s no surprise that tourism, too, has long been an important industry in the area.

The first hotel in Hubbards, built by Charles McLean in 1853, functioned as a stopover for stagecoaches travelling between Halifax and Lunenburg. A claim to fame for McLean’s Hotel is that Prince George, later King George V, was a guest there when he visited the area to hunt and fish. By the late 1800s, Hubbards had become a popular resort destination, drawing city dwellers from Halifax and tourists from the northeastern United States. More hotels were built, including the Gainsborough Hotel, opens a new window in 1884 and the Iona Hotel in 1905. Swimming, sailing, beautiful water views, and a relaxed rural charm were some of the area’s attractions. By the 1940s and 50s, Hubbard’s nightlife was another draw, featuring Big Band and jazz dances at the Shore Club and the Iona Dance Hall.

This photograph was taken near Dauphinee’s Point. At the top of the hill sits the Dauphinee Hotel, another establishment from Hubbard’s thriving hotel era. It was built by David Dauphinee in the late 1800s, and a three-story addition was added by his son Henry in 1905. The hotel was destroyed by fire in the mid-twentieth century.

References

-Fownes, N. (1990, July 27). Hubbards turns 200. Halifax Mail Star, B7.

-Fownes, N. (1990, July 28). Hubbards landmark being restored to former glory. Halifax Chronicle Herald, B5.

-Withrow, A. (1985). St. Margaret’s Bay: A history. Four East Publications.

-Withrow, A. (1997). St. Margaret’s Bay: An historical album Peggy’s Cove – Hubbards. Nimbus Publishing.

Golden Gates (Point Plesant Park Entrance)

Point Pleasant Park is one of Halifax’s most well-known and loved parks. This popular destination for tourists and residents boasts beautiful trails and views of the harbour and ocean. The park’s location on the south end of the peninsula has made it a very desirable location for its long history. The Mi’kmaq had been living on this land for generations to use its desirable access to water routes and hunting grounds. They referred to it as “the place of spirits”.

In Halifax’s earlier days, Point Pleasant was an integral part of the city’s defences. The British were hoping to minimize the French influence in North America and stationed the headquarters of the Royal Navy’s North American Station there. The defence system for Halifax Harbour was quite massive and employed a broad range of defences over the years. There were seven fortifications constructed. Most were rebuilt four or five times over 200 years. Some of the remnants of these fortifications are still intact. There are also several monuments around the park to commemorate those who have served in various war efforts.

In the eighteenth century, an American loyalist, Colonel Fanning, had the land cleared and built a stone house. In 1866, the British Government agreed to lease the 186 acres of parkland to Halifax. The deal was made for 999 years, costing Halifax one shilling per year.

The park gates seen in the postcard are also known as “The Golden Gates” and can be attributed to Sir William Young. He was one of the first Park commissioners and its first chairperson. He envisioned the creation of a public avenue with grand homes that lead to the park's entrance. He donated the gates and granite to create the pillars in 1866. The gates were designed by Edward Elliot, a Dartmouth-born architect who also designed Halifax City Hall several years earlier. They were made in Dartmouth by Starr Manufacturing Company, which, although it started as a nail company, the company is most famous for its skates.

Sir William Young died the following year, but before he passed, the city named Young Avenue in his honour. These gates were the original entrance to the park until the 1940s, when Miller Street became Point Pleasant Drive, and the gates were separated from the actual park. The gates can still be found at the corner of Young Avenue and Point Pleasant Drive. Although the gates are now another relic from a bygone era, they also remind us of the significance of the park in the city’s history.

References

- Halifax: Discovering Its Heritage by Stephen Poole. Halifax, N.S.: Formac Publishing Company Limited, 2012.

- Historic Young Avenue and Some of its Heritage Treasures, Young Avenue District Heritage Conservation Society, 2018.

- Point Pleasant Park: An Illustrated History by Janet Kitz and Gary Castle. Halifax, N.S.: Point Pleasant Publishing, 1999.