You wouldn’t know it today, but Halifax used to be pretty damp.

Wet, swampy, earth that fed multiple rivers and streams was once abundant scenes in and around the city. One of the most substantial of these waterways was Freshwater River, or Freshwater Brook. If you were to go for a stroll downtown today you might have trouble finding it. So what happened to this water source? Where did it go and where can we find it today? Let’s take a look at the history of Freshwater Brook and discover where it might be hiding.

A river runs through It

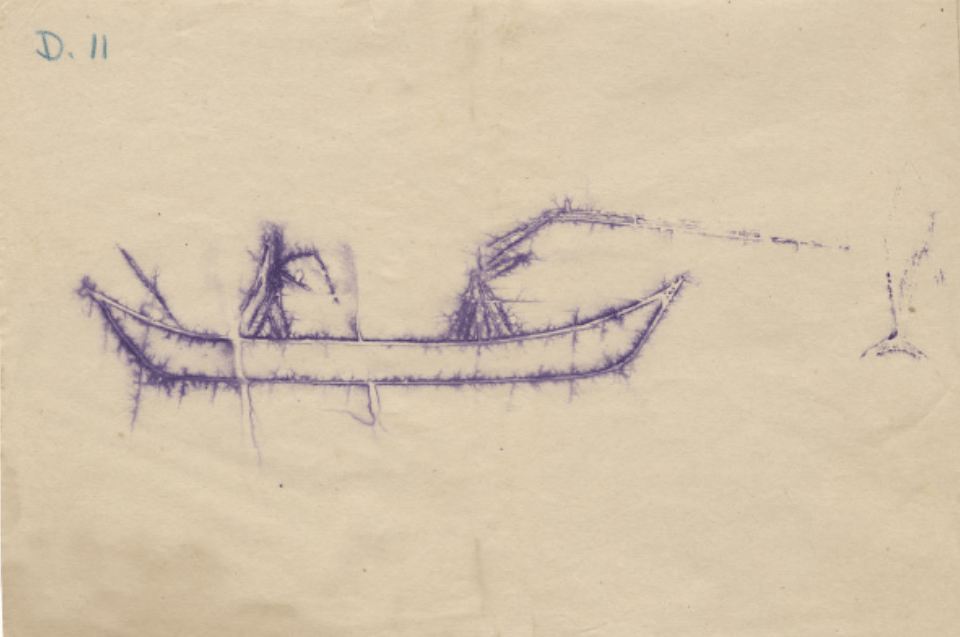

It’s hard to imagine—glancing around this modern city of concrete, steel, and glass—that Halifax was once a very different place. Where high rises, homes, and office buildings now stand there was once a landscape covered in greenery and water. Prior to colonialization, the Mi’kmaq—who had been living in Nova Scotia for thousands of years—made use of local waterways not only for travel by canoe, but also for seasonal fishing and gathering. The wetlands around Halifax, particularly near the Halifax Common, were a good hunting ground for moose, beaver, and duck. The traditional use of the wetlands and waterways by the Mi’kmaq was forever disrupted, however, when the British began the construction of Halifax in 1749.

Click through to view:

When the British first sailed into Halifax Harbour, it is estimated that nearly 83 hectares of wetlands and approximately 78 kilometres of rivers and streams flowed through the peninsula. Freshwater Brook is thought to have been one of the largest fresh water sources: “Freshwater Brook… originated in the north end, somewhere below Needham Hill and flowed northward into Fairview Cove, eastward near the dockyard and southward through the North and Central Common… before eventually reaching the Harbour near Inglis and Barrington Streets.” (Davis MacIntyre & Associates Limited, page 2).

Though not blessed with the most unique name, Freshwater Brook would have been of significance to the British for the same reasons it was to the Mi’kmaq: it attracted wildlife, helped propagate plants and offered a source of unsalted water - three very important components in supporting a growing colony.

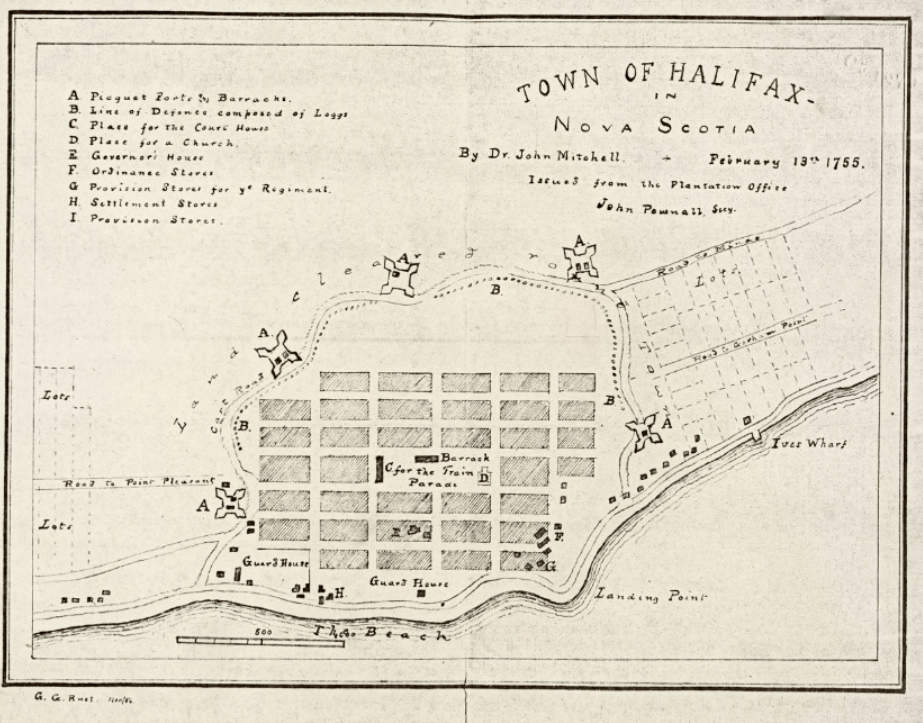

The British government’s initial design for Halifax began as a relatively small settlement. The downtown streets were laid out in a simple grid pattern surrounded by a palisade and five defensive forts. Freshwater Brook flowed outside of these boundaries, leaving it relatively undisturbed as the settlement process began. But Halifax was always intended to be a major seaport for the British, and before long it would outgrow its fortified walls.

As word spread about the newly founded British settlement at Halifax, people from across the colonies made their way to Nova Scotia. New Englanders traveled from the US coast, and immigrants from Germany, France, and Switzerland (known as as the Foreign Protestants) were recruited to make their way across the ocean. Halifax was going to need to expand. By the early 1750s, plans for Halifax’s sprawl were already being sketched out. Subdivisions outside of the palisade—the beginnings of what would become the city’s North and South Ends—can be seen on a map made by Dr. John Mitchell dated February 13, 1755. More people created the need for more food, and so by the 1760s/1770s a significant percentage of the peninsula had been cleared of trees to make room for farmland. The city was ever-developing, and with it Freshwater Brook would go through many changes.

Heading up to the North County

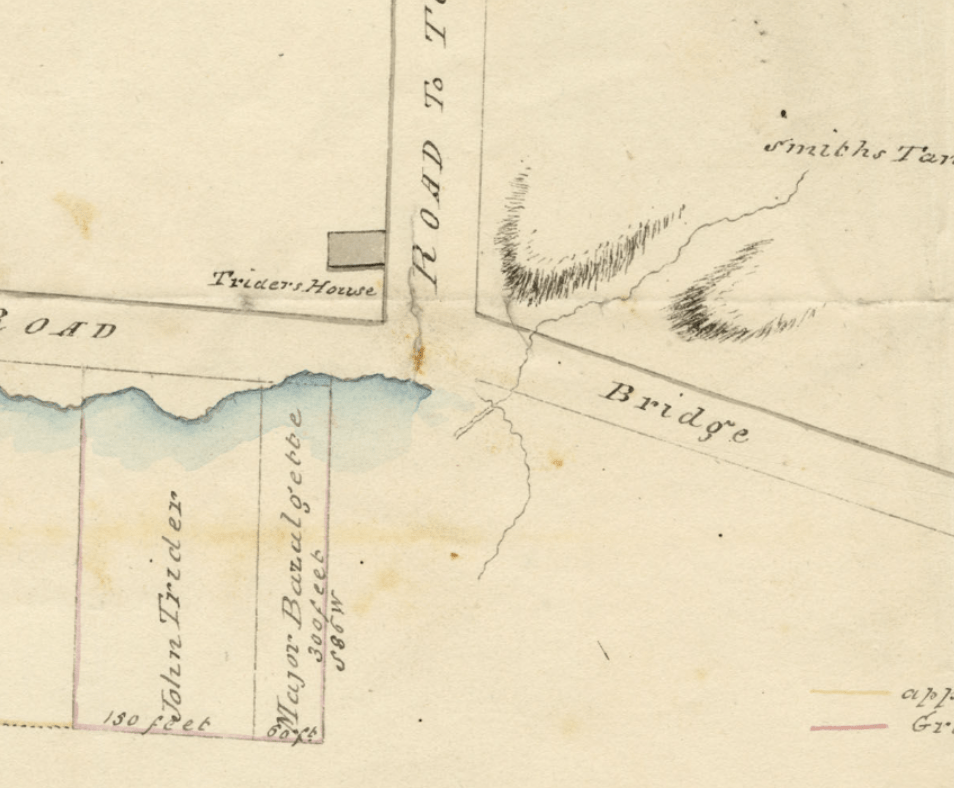

On Captain Charles Blaskowitz’s 1784 map, Freshwater Brook, along with several other streams, can be seen in the North End around Needham Hill. The area behind the hill, shaded in green, indicates marshland, which means a great portion of the area would have been significantly swampy. But that did not stop development in the area. City construction in the North End would take different forms, both military and domestic.

Fort Needham was constructed atop Needham Hill in the late 1770s as a reaction to the American Revolutionary War. It was intended to protect the Halifax Naval Yard from a potential American attack. The attack never came, and by the 1780s the fort had fallen into disrepair. The state of the fort would change for the better in 1807 when the British frigate Leopard captured the American Chesapeake. Chesapeake was boarded and several men who were believed to be British deserters were taken to Halifax, tried, and hanged. The Americans did not take kindly to this and many made calls to retaliate against Halifax specifically for their part in the ordeal. Due to the American threat, Fort Needham was rebuilt to protect the core of the city. As tempers cooled, the threat of invasion subsided, and less than 10 years after being rebuilt the fort was once again in ruins.

Domestic use of the land in the North End through which Freshwater Brook ran took some time to develop. Maps of the day—like the above Royal Engineers Map from 1808—indicate several tracks of land and some roadways, but very few buildings in the area. It is logical to assume that, much like the rest of the peninsula at this time, the area behind Fort Needham was initially used for farmland. This would have involved multiple changes to the landscape even above and beyond the clearing of trees. Settlers may have also been redirecting water to better drain the soil for cultivation:

Before 1900, some rivers and streams were deepened to provide better outlets. Ditches were dug by human and animal power to improve field drainage… Steam shovels [were] employed on larger drainage jobs from 1870-1930… Subsurface drainage by means of tiles, stones and wooden pipes was introduced in the mid-19th century…”

(“Farm Drainage”, The Canadian Encyclopedia)

Despite these changes, as of 1808 a faint waterway can still be seen wrapping around the back of Needham Hill and flowing near the Citadel on the above Royal Engineers Map. This suggests that Freshwater Brook was still present in the area at that time.

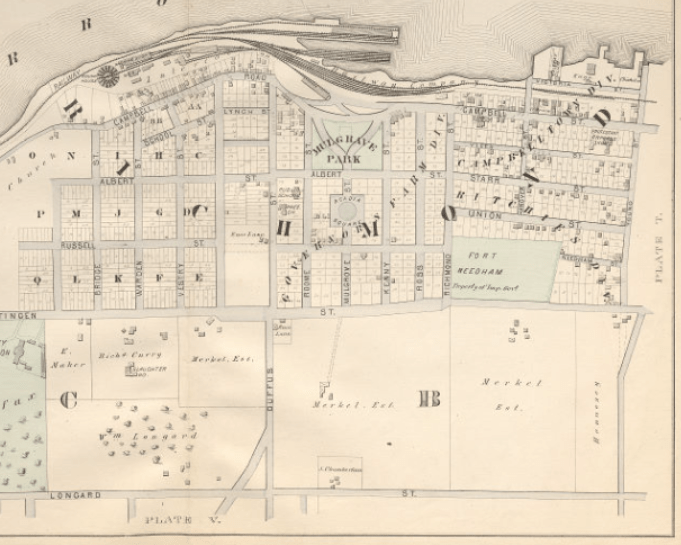

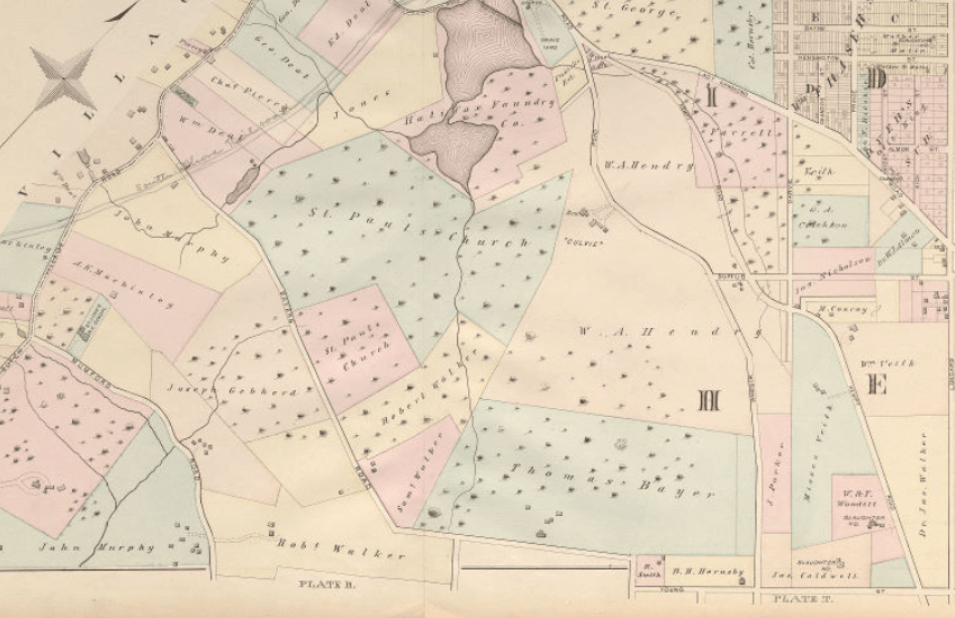

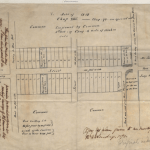

The first major residential development of the North End land around Freshwater Brook began in the 1860s with the Campbell Town development, so named after Campbell Road (now Barrington Street). This was followed by the Governor’s Farm division. Both of these were later known as Richmond. Like the downtown core, the roads in this part of town were set out in a grid pattern, and included now familiar streets like Needham, Young, Gottingen (later Novalea), Albert, Hanover, Veith, Kenny, Mulgrave, and more. By the late 1870s, the much beloved Hopkins Halifax City Atlas shows the street layout of the new neighbourhoods, along with scattered houses on the residential plots. The area on the far side of Gottingen Street was largely undeveloped, taking the form of large estate properties, open fields, or farmland. On the above portion of the Hopkins map, it should be noted that the waterway that once curled around Fort Needham has disappeared. Other steams and waterways are still indicated on the map.

For example, on the above section of the Hopkins Atlas showing Longard Street (now Robie) through to Dutch Village Road, several streams can be seen. Although Freshwater Brook’s exact fate in this area is not described in available sources, it can be surmised that the Brook was either filled in (to allow for more residential building plots, or the development of the Canadian National Railway), that it was forced underground (perhaps as one of the first sewage systems in the area), or some combination of the two.

Common down!

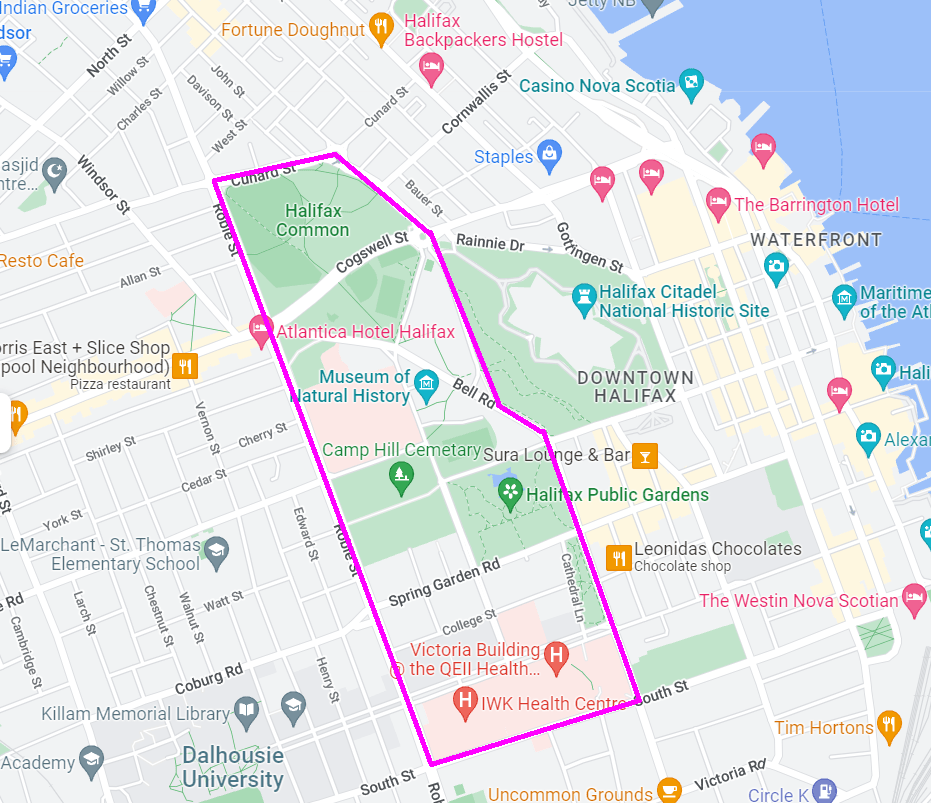

It’s hard to talk about Freshwater Brook without focusing on the Halifax Commons/South End Halifax.

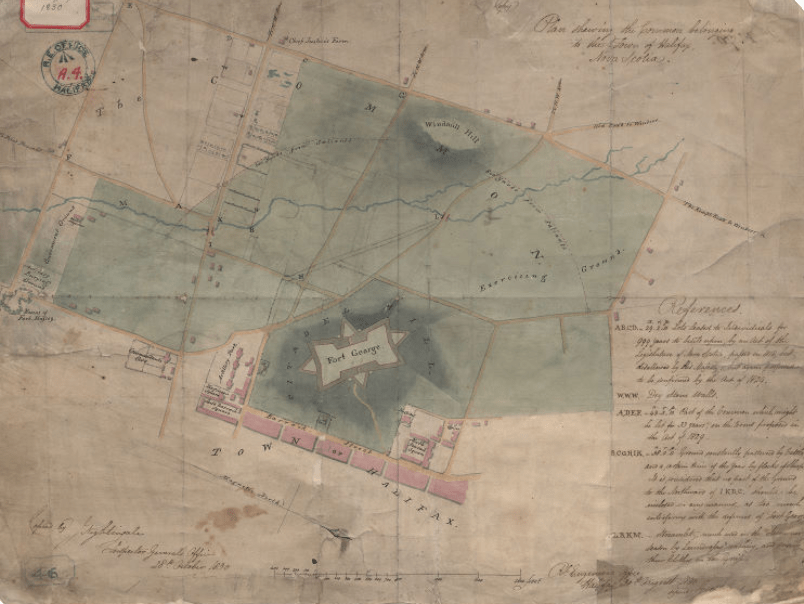

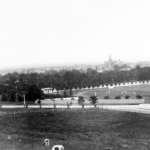

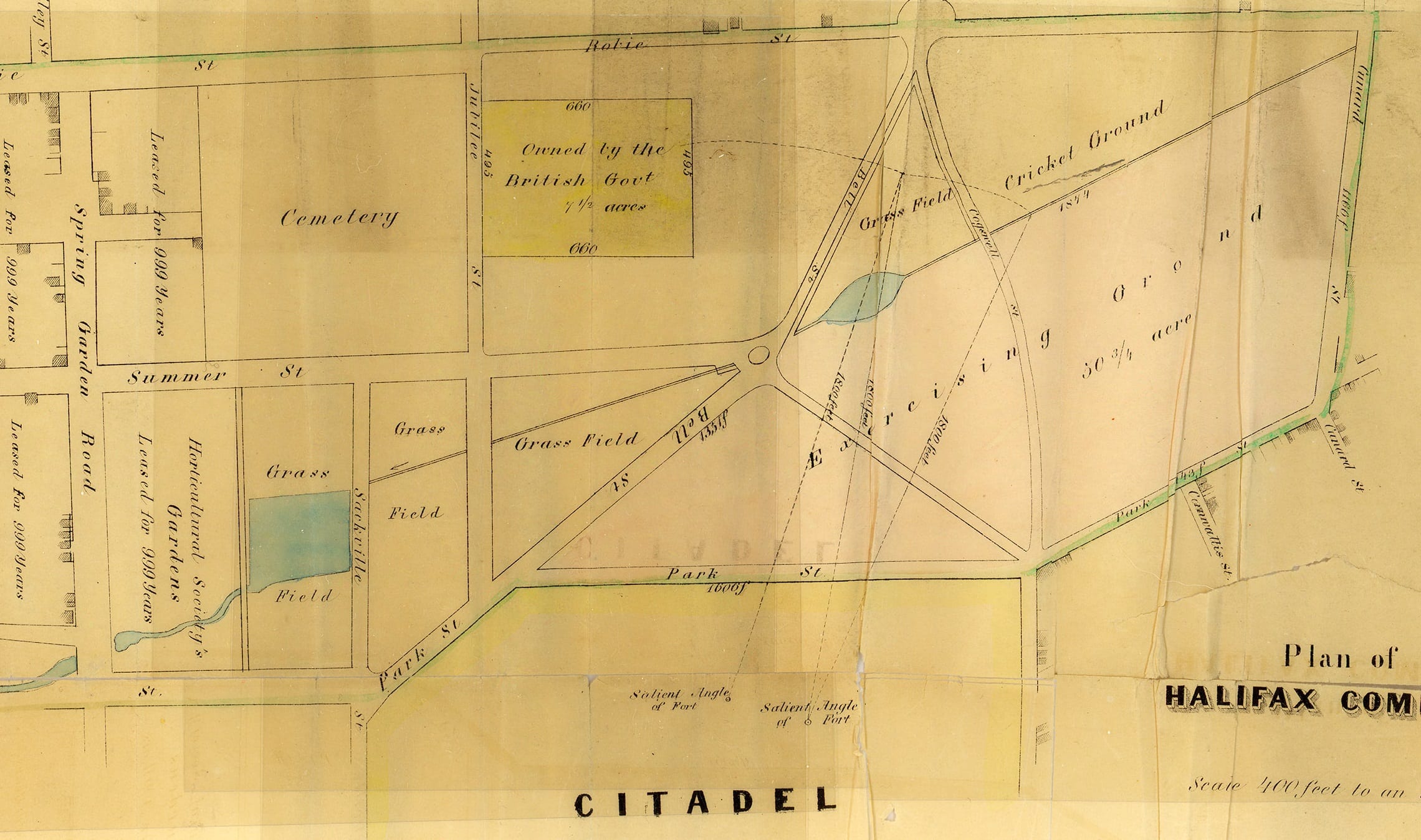

Common Land in British governing dates back to the Middle Ages. It was intended to be a green space that was free to be used as communal farm land by townsfolk, or “commoners”: “Before the easy availability of land drainage, there were always areas of farmland that were less productive, and difficult to improve. This ‘wasteland’ provided the essentials of life – food, water and fuel… the common land was accessible to tenants of the lord of the manor to provide further grazing [for animals].” (Association of Commons Registration Authorities). The grant for the Halifax Common, bestowed by King George III in 1763, consisted of 235 acres behind the citadel at Fort George.

The tract of land ran from Robie and North/South Park Streets and between Cunard and South Street. The space was not just used by commoners who let their animals out to graze or to collect firewood for their homes; the military also used it as a training ground of soldiers.

Freshwater Brook ran from the North End directly through the Commons. Despite its practical uses, the military considered it to be more of a hazard because “…the deep busy ravine of the Freshwater River offered perfect cover to an enemy approaching the south flank of Citadel Hill.” (Raddall, p. 92). It was this fear of a southern attack that later inspired the construction of Fort Massey in the late 1770s.

After flowing through the Commons, Freshwater Brook made its way into South End Halifax:

The Brook continued under Pyke’s Bridge west of what is now the intersection of South Park Street and Spring Garden Road, and after skirting the eastern side of the present Victoria Park and the School for the Blind property, turned southeast, dropping over a small waterfall into the ravine below South Street… Just west of Queen Street Fresh Water Brook was joined by another stream which ran from the Poor House Pond…

Blakeley, page 180

At the end of its course, Freshwater Brook emptied into the harbour near the bottom of Inglis Street. Here, a bridge referred to as Kissing Bridge, crossed over the Brook near where it drained into the sea. The bridge was a popular spot for courting couples to take an evening stroll and exchange romantic flirtations.

At this time, the brook was large enough and strong enough to support local mills and businesses. William Artz, for example, used the brook to power his South End tannery. The business was located between Fenwick and South Streets, approximately where The Vuze stands today.

Click through to view:

Over time, the needs of the city began to change. Farming in downtown Halifax was gradually phased out and moved outside the city; the need for livestock to casually graze close to the downtown core became a thing of the past; and the military stopped using the space for drill exercises. The Commons were no longer needed for their original purpose, so what was to become of it? As it happens, lots of things! The Public Gardens, The Wanderer’s Grounds, Camp Hill Cemetery, Skating Rinks, Schools, Hospitals, The CBC Television Building, the Museum of Natural History, Sporting Fields/Courts, a Skate Park, private land grants: all of these and more were built on the Commons land. But what happened to Freshwater Brook?

Click through to view:

For the most part, Freshwater Brook became a hidden asset.

In some instances, the brook was filled in to create dryer land. An example of this is the area around the Emera Oval pavilion on Cogswell Street. During an archaeological exploration, a discovery was made: “Below the 20th Century material was a layer of mid-19th to early 20th century domestic refuse… Below this stratum was a layer of ironstone “cobbles” and boulders at the level of the water table which was interpreted as a 19th century infilling episode to address the wet, swampy conditions of this part of the Common” (Halifax Common Master Plan, page 100). This is also very evident with the disappearance of Black Duck Pond, later known as the Egg Pond. Once a local spot for boating, swimming, and skating, the pond was drained in 1995 and filled with concrete to create a skateboard park referred to as The Bowl.

In other places, the brook was redirected. This resulted in much of the brook being used for a practical, if not so glamorous, purpose: “As the 19th century progressed, parts of Freshwater Brook were diverted and later channelled through culverts… Eventually, the brook was fully channelled through underground pipes, becoming a sewer.” (Halifax Common Master Plan, page 25). Occasionally, elements of this sewer system have been unearthed. This happened as recently as December of 2020 when a rock-and-mortar pipe was discovered during a dig near the Museum of Natural History. Stephen Archibald, a former employee of the Museum of Natural History, says that when the Museum was built in 1970, it was built directly on top of the brook’s path: “When I worked in the museum, the freight elevator would regularly descend to a pit filled with brook water. Splish Splash.” (Archibald, Halifax Bloggers).

When the pipe was uncovered, concerned citizens began a rallying cry to return the brook to the surface. In a Saltwire.com article, James Campbell commented: “We daylighted a section of Sawmill River, which is over in Dartmouth… which was a great success… But we haven’t been involved in any discussions about daylighting any sections of Freshwater Brook…” (Campbell, Saltwire.com). Whether or not talks regarding restoration of the Brook will occur in the future is unknown.

Hiding in plain sight

Click through to view:

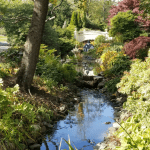

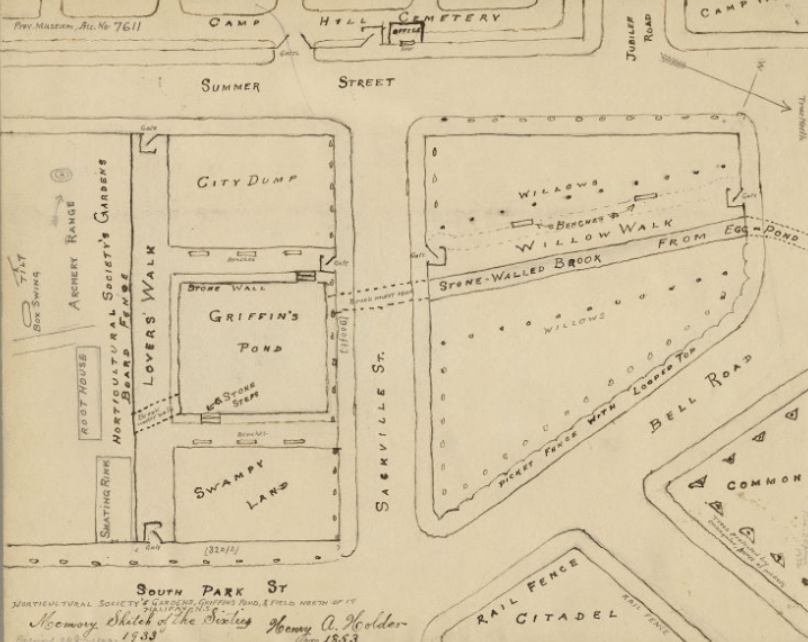

Though the bulk of Freshwater Brook is now hidden from view, an element of it still remains. Nestled in the Public Gardens is Griffin’s Pond, a man made body of water that is home to waterfowl, plant life, and – during the summer months – a scale model of the HMCS Titanic. Griffin’s Pond is said to be named after a young Irishman named Lawrence Griffin who was hanged at the pond’s banks in 1821 after being convicted of murder. This conviction that was later called into question. Freshwater Brook was the original water source for Griffin's Pond.

Over time, Griffin’s Pond has been transformed multiple times. When it was first constructed, the pond was surrounded by stone and square in shape. However, in the 1870s, garden Superintendent Richard Power decided to change the layout of the pond to give it a more natural look: “In 1878 and 1879 the ugly walls surrounding the square Griffin’s Pond were removed, the sides sloped and sodded to transform the Pond…” (Blakeley, p.176). A more recent change to the pond is difficult to see by design. After the destruction caused by Hurricane Juan in 2003, a closed circuit water recycling system was implemented in the pond. The pump station is cleverly hidden in the waterfowl house.

For the time being, a stroll through the Public Gardens is the only way to view what remains of Freshwater Brook.

The Finishing Lines

Freshwater Brook is but one of many natural landmarks that have disappeared from the public eye in Nova Scotia. Is it possible, practical, or wise to return Freshwater Brook to the surface? That is uncertain. It is important, however, to remember the role that Freshwater Brook played in our collective history. So the next time you’re passing through the Public Gardens, take a moment to stop and enjoy what remains of this water source that once flowed through our city.

Library Sources

An Investigation of the Development of the Common of Halifax, Nova Scotia

On the Road From Freshwater Bridge

Photographs

Blaskowitz, Charles. A Plan of the peninsula upon which the Town of Halifax is situated…, 1784, Library and Archives Canada

Bollinger, E. A., The Public Gardens, 1941 Halifax NSA 1975-305 1941 no. 424b

Building Lots on the Halifax Commons, 1831, Nova Scotia Archives Map Collection, V6 240,

Creed, George, Tracing of a petroglyph of a human figure in a canoe lancing a fish, Mi’kmaq Petroglyphs, 1888, Nova Scotia Archives, MG 15 Vol. 12 D11

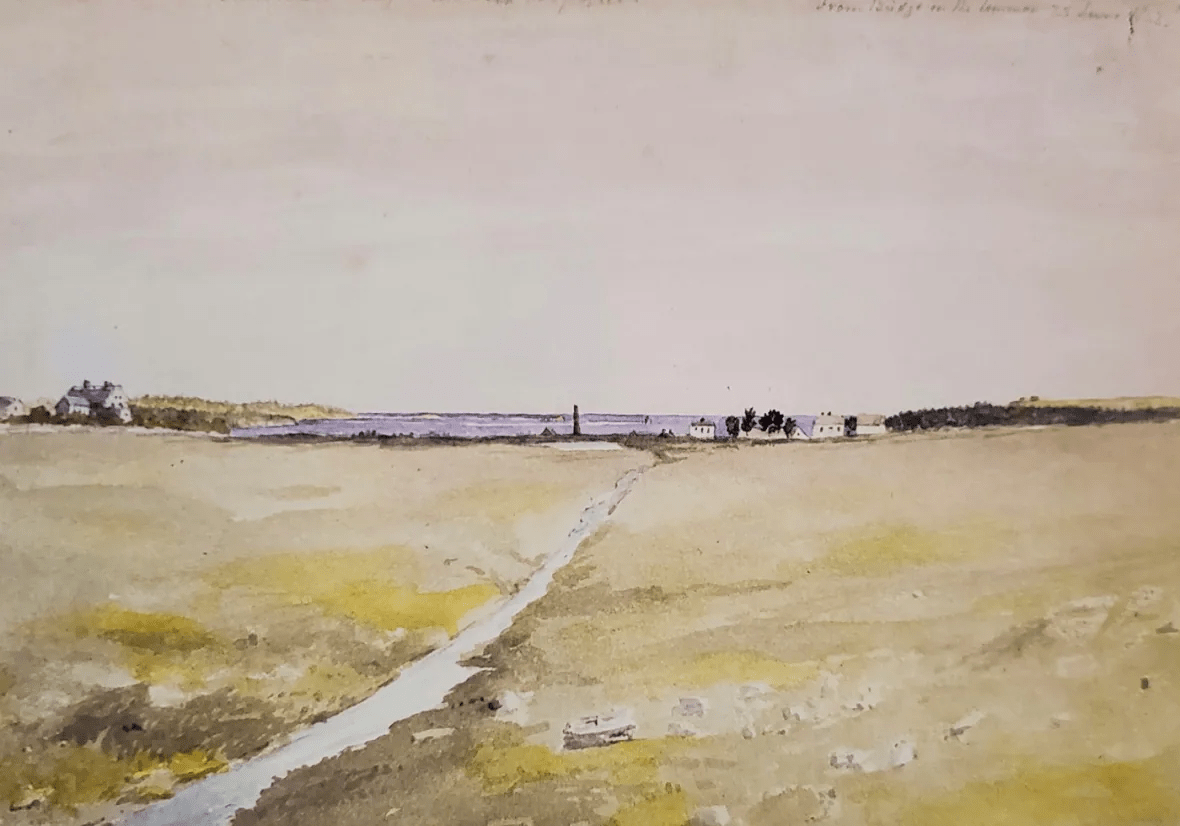

Day, Forshaw, Freshwater Brook, Halifax, 1858, Nova Scotia Archives, Bollinger negative no 49105, 50215

Guertin, Robert, Halifax Parkade Construction Provides Rare Glimpse of Historic Hidden Watercourse, CBC, December 2020

G. W., Halifax – Commons, 1830, Nova Scotia Archives, Royal Engineers Maps and Plans, A.04

Halifax, Google Maps, June 18, 2022

Hirtle, Patrick. Softball on the Commons, 2021

Hopkins, H. W., City Atlas of Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1878, plates U and V, Nova Scotia Archives, O/S G 1129 H3 H67 1878

Horticultural Society Gardens Griffen's Pond & Field to north Halifax, 1860, Nova Scotia Archives F/240 – 1860

MacAskill, W. R., Bridge in the public gardens, Halifax NSA 1987-453 no. 2610

MacAskill, W. R., Bridge over pond, Public Gardens, Halifax NSA 1987-453 no. 4088

MacAskill, W. R., Egg Pond, Commons, Halifax, NS, Nova Scotia Archives, 1987-453 no. 4501

MacAskill, W. R., The Public Gardens, Halifax NSA 1987-453 no. 2045

MacAskill, W. R., Punting on the Egg Pond, Halifax Central Commons, Nova Scotia Archives, 1987-453 no. 2626

MacAskill, W. R., Swans, Public Gardens, Halifax NSA 1987-453 no. 4110

Mercer, Alexander C., Freshwater Brook, 1842, Halifax Parkade Construction Provides Rare Glimpse of Historic Hidden Watercourse, CBC, December 2020

Messervey, Victoria, Various Photos, 2021-2022

Mitchell, John, Map of Halifax, 1755, Nova Scotia Archives Map Collection: F/240 – 1755

Notman Studio, Wanderer’s Grounds, 1889, Nova Scotia Archives, 1983-310 number A-96

Toler, John G., Peninsula and Harbour of Halifax, 1808, Nova Scotia Archives, Royal Engineers Maps and Plans, Y.26

Town of Halifax in Nova Scotia, 1755, Nova Scotia Archives, F/240 – 1755

Water Lots at the foot of Inglis Street, 1816, Nova Scotia Archives Map Collection, F/240 - 1816

Articles and References

Archibald, Stephen, Not So Fresh, Halifax Bloggers, 2020

Association of Commons Registration Authorities, The History of Common Land and Village Greens

Beck, J. Murray, Nova Scotia, The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2021

Broughton, R. S. and Jutras, P. J., Farm Drainage, The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2013

Campbell, Claire, A Working Waterfront: Water and Public Memory in Halifax, Niche, 2020

Davis MacIntrye & Associates Limited, Halifax Common Master Plan: Archaeological Resource Impact Assessment Appendix C, 2018

Davis MacIntrye & Associates Limited, Schematic Design of Spring Garden: Archaeological Resource Impact ASsessment Appendix A, 2018

Department of Energy and Mines, Groundwater Atlas

Friends of the Halifax Common, Celebrate the Common 250, 2013

The Friends of the Public Gardens, Garden Features

Halifax and Its People, 1749-1999, Nova Scotia Archives

Halifax Military History Preservation Society, Fort Needham

Julian, Jack, Halifax Parkade Construction Provides Rare Glimpse of Historic Hidden Watercourse, CBC, December 2020

New Map of the City of Halifax Compiled from the most recent surveys, 1869, Nova Scotia Archives Map Collection: V6 240

Tulloch, Tom, Defending Halifax, The Early Fortifications, Halifax Military Heritage Preservation Society

Walker, Edmond, Fort Needham – Naval & Ordnance Property, 1850, Nova Scotia Archives, Royal Engineers Maps and Plans A.15

Add a comment to: Whatever Happened to Freshwater Brook? – A Brief and Not At All Definitive History