written by Amy, staff member, Halifax Central Library

Nova Scotia Heritage Day

Nova Scotia Heritage Day is a relatively new statutory holiday that Nova Scotians began to honour in 2015. It is celebrated every year on the third Monday of February. Each year, one important cultural or historical Nova Scotia person, place, or event is honoured on this holiday. Past honourees include Viola Desmond, Mi’kmaq Heritage, and Africville. The honouree for 2022 is The Landscape of Grand Pré World Heritage Site.

The Landscape of Grand Pré was selected as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2012 to honour both its cultural and agricultural legacy. It recognizes the Acadian deportation that began in 1755 as well as the agricultural achievements they realized before being forced to leave. The region is located in the community of Grand Pré in the Kings County, Nova Scotia, near Wolfville.

History

The first residents of the Grand Pré area were the Mi’kmaq. They called it Setnog or Chdnouk, meaning “extending out into the sea.” It was also known as Galipotjegatiq or “little caribou place” (Johnston and LeBlanc, p. 25). They lived, travelled, camped, and fished in the area.

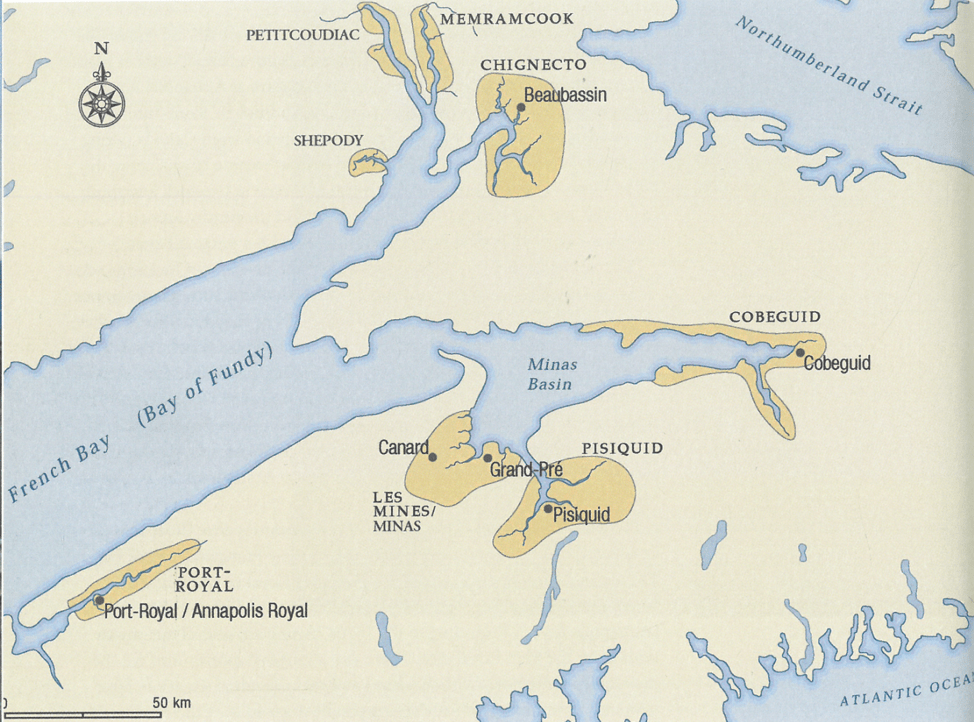

French settlers travelled to Nova Scotia intermittently in 1598, 1604, 1610, and 1632. French families travelled to Nova Scotia to settle at Port-Royal (now Annapolis Royal) in 1632 after it was returned to the French. By 1650, 50 families—about 400 people—lived in the region. They soon spread out to other regions including Chignecto, Pisiquid, and Cobeguid.

The Acadian settlers had a friendly relationship with the Mi’kmaq because of their shared religious faith in Roman Catholicism. Marriages were common between Acadians and Mi’kmaq.

The region was called ‘Grande Pré’ by the French, meaning “the great marsh” which reflected the landscape (Johnston and LeBlanc, p. 31). The number of families grew over the years and many resettled to the Grand Pré area in 1680. They built dykes and began to farm; it was the most populous Acadian settlement.

“The community included houses, farm buildings, orchards, gardens, storehouses, windmills, and the parish of Saint-Charles-des-Mines.” -(Johnston and LeBlanc, p. 55-56).

Landscape

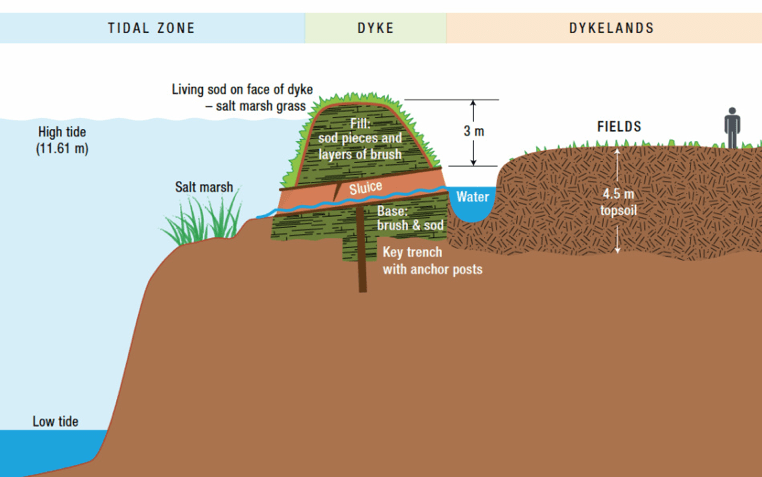

Grand Pré is situated on the Minas Basin, an inlet of the Bay of Fundy, and has the highest tides in the world. The wetland here is marshy and muddy. The Acadian settlers transformed the landscape to an agricultural centre with the construction of dykes and aboiteaux. The construction of the dyke walls, sluices and hinges controlled the flow of seawater onto the land.

The newly dry lands on the other side were then desalinated and used for farmland. It was an incredible feat to transform the land. They planted fields of wheat, rye, oats, peas, flax, and hay, and planted fruit tree orchards.

Strife and uncertainty

Acadians lived in Nova Scotia during times of uncertainty as France and Britain fought for control of the region. Mainland Nova Scotia passed to the British in 1713 with the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht. In 1740, war broke out between the two imperial forces, which led to attacks at Annapolis Royal in 1745 and at Grand Pré in 1747. After the war, Île Royale (Cape Breton) was returned to the French in 1748. During the war, the Acadian people wished to remain neutral. Yet, due to their French heritage, the British viewed the Acadians as a threat.

The Acadian Deportation

The founding of Halifax in 1749 as a British settlement strengthened British numbers. Governor Cornwallis demanded that the Acadians declare an oath of allegiance to the British, which they refused to do, and maintained their neutrality. Worried, many Acadian families left the British-controlled area to move to French territory in Île Sainte-John and Île Royale.

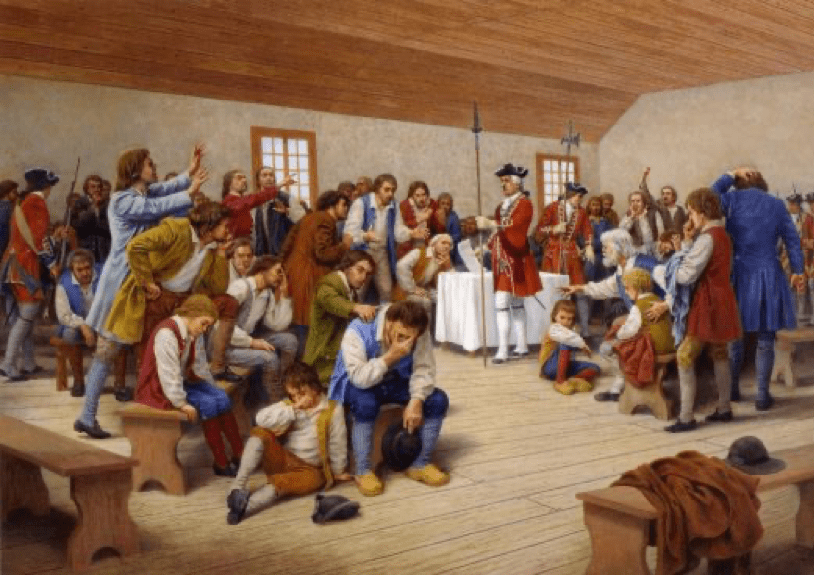

In June 1755, a British regiment attacked and captured the French-controlled Fort Beausejour (on the isthmus of Chignecto) and renamed it Fort Cumberland. During this siege, the French commander had threatened 300 Acadian men to assist in the fort’s defense. The British governor Charles Lawrence in Halifax was angry that Acadian men helped to defend the French. He ordered the deportation of all Acadian men, women, and children from Nova Scotia.

In August 1755, every Acadian man and boy over age ten in the Chignecto region was summoned to Fort Cumberland for an announcement. Instead, they were all immediately arrested and imprisoned. The decree that was read stated in part:

"That your Land & Tennements, Cattle of all Kinds and Livestocks of all Sorts are forfeited to the Crown with all other your effects Savings your money and Household Goods, and you yourselves to be removed from this Province."

Acadian men in Grand Pré were similarly rounded up in September 1755. The men were stunned, shamed, and angry.

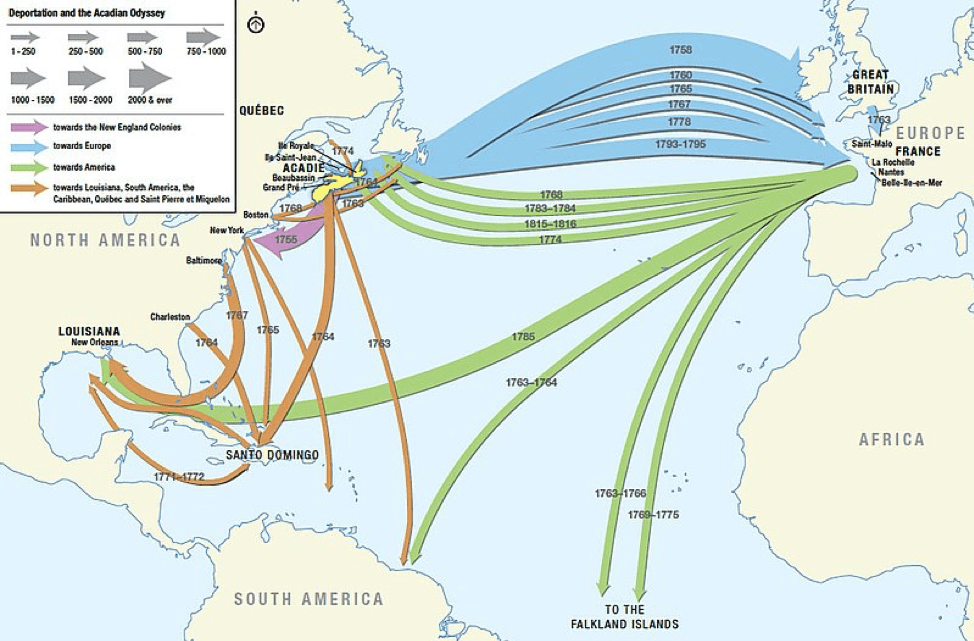

Many Acadians in the region fled as soldiers moved through their villages and burnt down their homes and buildings. Some hid in the woods or fled to French-controlled regions in Île Royale or New France. In October 1755, the first ships of Acadians set sail from Horton Landing.

In the first month of the deportation, over 1,500 Acadians were put onto transport ships and forced to leave their homes. By the year’s end, over 6,000 Acadians were deported. Ships were sent to American colonies in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Maryland, Connecticut, and Massachusetts.

Later, other ships were sent to Britain colonies, France, or the Caribbean. The refugees were not welcomed to their new lands. In Virginia, they were rejected and forced to leave again. In other places, they suffered through poverty and illness. Many Acadians felt they had lost their sense of identity in the American colonies.

The deportation of the Acadians continued until 1762. Approximately 10,000 people had been forcibly removed from their homes.

New settlers and legacy

New England Planters arrived in 1760 and called the area Horton Township. They repaired the dykes, rebuilt the buildings, and settled into the region. The agriculture of the region flourished under their care. Later, the name of the town was changed back to Grand Pré in the 1860s.

Over the years, many Acadians did return to Nova Scotia and settled in new communities.

In 1847, poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote his epic poem, Evangeline, A Tale of Acadie. It tells the tale of a young Acadian woman who was separated from her love during the deportation and searches for him throughout her life. The poem and the characters of Evangeline and Gabriel became enormously popular. Admirers travelled to Nova Scotia to visit the land of Evangeline. In 1908, the Province of Nova Scotia declared the Grand Pré region as “Historic Grounds”

The Dominion Atlantic Railway bought the entire property in 1917 and began the work of developing it. They landscaped a new park and commissioned a statue of Evangeline in 1920.

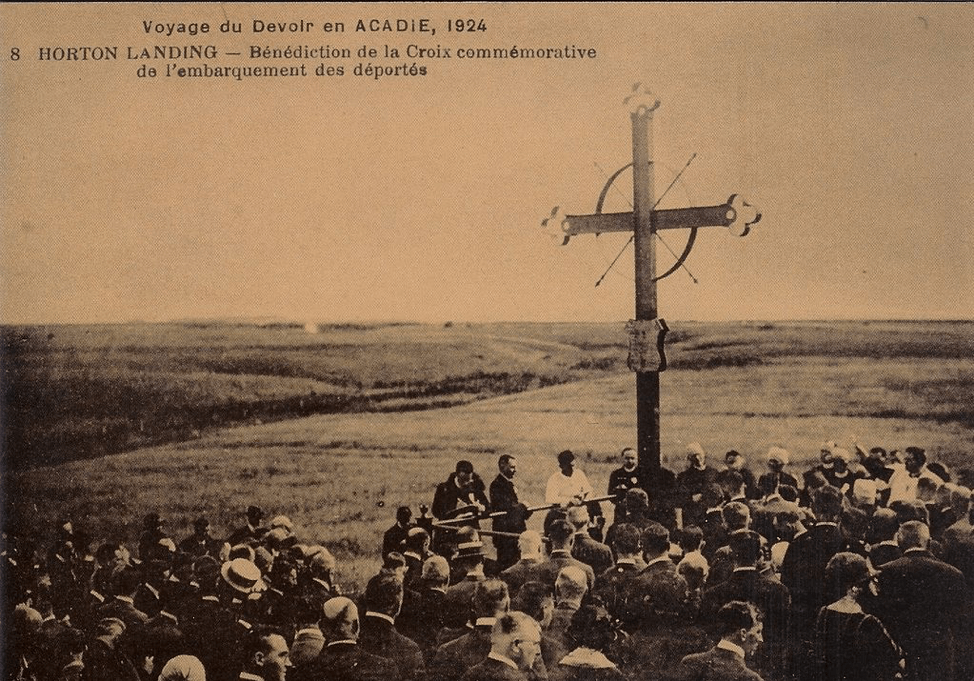

In 1922, the memorial church was built and dedicated as an Acadian memorial. Another solemn memorial is the iron cross known as the Embarkation Cross, which was erected in 1924. It marks the site of the deportation from Horton Landing.

The Grand Pré site became a national historic site in 1961. It was determined that:

“Grand Pré Park is considered the most important Historic Site by the Acadian people…it recalls their saddest and most heroic moments and…must remain for future generations the example of courageous people whose culture and actions shall enrich more and more the Canadian nation” (Johnston and Kerr, p. 75).

In 2012, the site was chosen as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and in 2022 it is honoured on Nova Scotia Heritage Day. The legacy of the Acadians’ ingenuity in reshaping their landscape is persevered in Grand Pré. So, too, is the painful tragedy of their expulsion.

Library resources

Links and sources

- Nova Scotia Heritage Day (NovaScotia.ca), opens a new window

- The Landscape of Grand Pré Nova Scotia, opens a new window

- Google Arts and Culture. Landscape of Grand Pré, opens a new window

- Grand Pré: A UNESCO World Heritage Site (NovaScotia.ca)

- La désignation de Grand-Pré comme site du patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO, opens a new window

- The Canadian encyclopedia. Acadian Expulsion (the Great Upheaval), opens a new window

- UNESCO World Heritage Site (UNESCO), opens a new window

- Evangeline, Tale of Acadie (Poets.org), opens a new window

Add a comment to: Nova Scotia Heritage Day Honouree 2022 – The Landscape of Grand Pré